Anna Bagnoli (2004) 'Researching Identities with Multi-method Autobiographies'

Sociological Research Online, vol. 9, no. 2, <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/9/2/bagnoli.html>

Received: 26 Jun 2003 Accepted: 26 Apr 2004 Published: 31 May 2004

Abstract

In order to research the identities of young people in contemporary Europe I designed a participatory project which relied on the application of a multi-method autobiographical approach. The project fully involved the young participants as co-researchers, assigning them a guiding role, and allowing them to provide the identity narratives which were most significant to them, in their own terms. The multi-method autobiographical approach that I present here was designed so to study identities as dialogical constructions, on the basis of a holistic 'self+other' model, which assumes that the dimension of dialogue and the relationship with the other from us are fundamental in the process of identity definition. Main aim of the approach was encouraging reflexivity, and it offered a variety of media for the young participants to narrate their life-stories. Centring on the production of a one-week diary, it involved also two open- ended interviews, as well as the use of visual methods, the projective technique of the self-portrait, and the collection of participants' own photographs. The young people responded enthusiastically to this methodology, which sometimes also empowered them over their lives. Its flexible and open structure effectively allowed them to guide the research in the directions they wanted, being sensitive to their own preferred ways of self-expression. The use of written and visual methods significantly widened the area of research, accessing data that might have been difficult to gather otherwise.Keywords: Autobiographical Research; Dialogical Self; Identities; Visual Research; Young People

Introduction

1.1 Identities have become problematic in the contemporary world. In answer to the rapid social changes which characterise our daily lives, existing identities may easily prove inadequate and in need of reconstruction. Defining an identity is particularly complicated for young people, for whom the experiences made by previous generations soon lose any significance as viable patterns for their lives. My PhD research at the Centre for Family Research of the University of Cambridge explored the ways in which young people construct their identities in contemporary Europe in such an uncertain context (Bagnoli, 2001)[1]. My aim in this research was asking young people themselves to describe their lives and identities in their own terms. On this purpose, I designed a participatory project, which aimed to fully involve the young people taking part as co-researchers, and possibly also to empower them, contributing to a greater awareness over their current life-trajectories.

1.2 From an epistemological point of view, a participatory inquiry relies on a view of knowledge as inescapably grounded in the researcher's own subjectivity, as pointed out by feminist social science (Stanley and Wise, 1993), and as collaboratively produced between the researcher and the people being researched. Since my aim was gaining entry into young people's phenomenological worlds, recording their lives in as much richness and multiplicity of aspects as possible, a qualitative methodology was particularly appropriate. I therefore worked to develop a methodology which would encourage the young people to express themselves as they wished to, whilst adhering as closely as possible to their own perspectives, their terms and definitions of themselves and their lives. Keeping a holistic frame in mind for the study of identities, which would consider young people within their social networks and on a variety of dimensions, my aim was to be sensitive to what would emerge in the field from the respondents' own voices. Autobiographical methods were thus the ideal choice, because of their capacity to enter people's lives and register them in detail.

1.3 The result of this methodological work was the multi-method autobiographical approach that I present in this article. The following sections review the choice of autobiographical methods as particularly suited to study identities on a dialogical and inclusive model. The different methods included in the approach, which ranged from the more standard open-ended interview to visual and written sources, are described in detail and in their combined application. By drawing on case study evidence from this research, I point out the advantages, as well as some of the potential drawbacks and unintended consequences, of adopting an autobiographical and multi-method approach to social research, and suggest the present methodology as a particularly effective one to study identities in the contemporary world.

Narratives of identity: the relevance of autobiography to the study of identities

2.1 This research has adopted a relational, 'self+other' model, for the study of identities. Constructed on the assumption that we define our identities in a dialogue with the other, through the relationship to what we are not, this is a holistic model which challenges the standard Western notion that a boundary differentiating and opposing the self to the other should be fundamental in the process of identity construction (Paasi, 2001), on the basis of recent dynamic theories of the self.

2.2 As outlined in the theory of 'possible selves' (Markus and Nurius, 1986), an array of different and even contradictory self-representations make the totality of our self-knowledge, framing the direction of our future actions. Possible selves may act as incentives and role-models, representing our goals and what we would like to be, our wished-for selves, or else they may stand as threats and feared selves, and remind us of what we are afraid of becoming. Borrowing Hermans''dialogical self' (Hermans, 2001), they may be viewed as multiple voices speaking within the same subject, and engaging in a process of inner dialogue between different and contrasting worldviews.

2.3 The pole of the other, which in this perspective significantly contributes to the shaping of identities, can thus be broadly understood as a multiplicity of voices, arising from both within and without the subject. Present within one's individual consciousness in the form of representations of significant others, this other can be thought of as pertaining to the world of everyday experience, as well as to the world of one's imaginary. Either when acting as role-models or when as threats, these representations may thus directly arise from our own past life experiences, but can also be based on the inner dialogue we may entertain with figures which have a mere 'imaginal' quality (Hermans, Rijks, and Kempen, 1993), yet still a significant centrality to our lives.

2.4 A dynamic construct, the 'self+other' model presents a number of advantages for the study of identities in the contemporary world. Its dialogical nature makes it possible to look at identities on a multiplicity of dimensions, accounting for the presence of contrasting narratives within one's self-construction. By focusing on the process of dialogue between self and other, this model is able to read identities as socially constructed, emerging out of people's social contexts and networks of significant others. Its attention to the different voices speaking within the self also allows it to integrate the dimensions of change over time, uncertainty, and the imaginary, since it can consider the possible alternative constructions that might be present within one's own consciousness.

2.5 This open character makes the 'self+other' model able to read the ways in which identities are defined in conditions of uncertainty such as those which are typically lived in late modern societies. In a global and 'postcolonial' world (Bhabha, 1994), where the cultural other is increasingly becoming a pervasive part of our daily lives, this model can study identities as hyphenated and hybrid constructions (Caglar, 1997), made of heterogeneous elements, multiple and contrasting voices, thus appreciating the complex ways in which different cultures participate in their definition (Hermans, 2001). Through its ability to venture into the imaginary, the relevance to identities of constructions which are coming from spatially distant contexts and lack a grounding in local traditions (Giddens, 1991) may also be appreciated.

2.6 Thanks to its attention to the different narratives and contrasting worldviews which together contribute to the process of identity construction, the dialogical dimension can aim to read the extent to which identities may respond to the logic of dominant, context provided constructions, or to alternative discourses and narratives of resistance (Smith, 1993). The narrative framework is an approach sensitive to social complexity, which is able to appreciate the ways in which people negotiate and position themselves between different discourses, thus allowing the asymmetries in power which exist in societies between cultures and social groups to emerge (Hermans, 2001).

2.7 Identities may thus be read in their intrinsically social nature, in terms of the stories that we construct in order to make sense of the events in our lives, and that allow us both to reach a self-understanding and to communicate that understanding to others (Gergen and Gergen, 1988). Emerging out of an ongoing activity of self-reflection and out of a process of dialogue, these narratives are the result of a negotiation process between the stories that we tell about ourselves and that others tell about us. Since multiple stories can be told about life-events, narrative choice also corresponds to some positioning of the self in society. The narrative approach traces the ways identities are defined in 'context of practice' (Bruner, 1990), on the grounds of the particular, everyday details of people's lives, as they appear in their autobiographies.

2.8 Autobiographical methods are therefore the ideal tool to study identities in a dialogical and narrative perspective. A wide variety of methods may be termed autobiographical: any 'documents of life' (Plummer, 2001), ranging from life-histories to diaries, letters, archival records, photographs, films, and personal possessions, which share the fundamental characteristic of being a potential window onto people's lives. Autobiographical research can explore individual lives with receptivity to people's own meanings and understandings. Every autobiographical story is, however, an 'artful construction' (Stanley, 1992): the idea that autobiography may represent the 'whole life' of a person is a fiction, which relies on the assumption that we are integrated individuals with a coherent and truthful story to tell, as dictated by the Western ideology of bourgeois individualism (Evans, 1999). Autobiographical memory has a selective nature (Neisser, 1982), and the life stories that we narrate, typically imposing some chronological order and links of contiguity upon events, respond to the narrative conventions and self construction canons of our societies.

2.9 The active role of the reseacher as auto/biographer and the interaction between the participants' and the researcher's subjectivities is another central feature of the autobiographical approach. The 'auto/biographical I' (Stanley, 1992) studies other people's lives grounded in her or his social location: just as the selves under study are considered within their network of significant others, and not in isolation from their context, so too the researcher's subjectivity is present throughout the research, and resonates of the themes raised in the inquiry (Stanley, 1993). The adoption of such a reflexive approach in research may thus ultimately result in personal growth for the researched and researcher alike.

From Diary Study to Multi-method Project

3.1 In order to make the potentialities of the 'self+other' model operational, my work of methodological design aimed to: encourage reflexivity, so as to be able to read into the self+other dialogue; enter the imaginary, being able to appreciate people's own worlds, their dreams, models, and aspirations for the future, as well as the patterns crystallised from their past; provide a degree of flexibility which would suit the method to the needs and expressive styles of different people.

3.2 I started out planning this research as a diary study since, as a diarist myself, I was intrigued by the possibilities of the diary for the purposes of a holistic, dialogical, and participative study of identities. With the potential of accessing individual lives as they are lived, registering the flow of events just as they occur, and in the author's own voice, the diary has a characteristic flexibility which makes it the 'document of life par excellence' (Allport, 1942). Offering the possibility of being intermittent in one's writing, it is a fluid instrument where the boundaries between author and reader, art and life, present and past selves, as well as self and other, are characteristically shifting (Watson, 1988). Diaries may be written in a multiplicity of formats, depending on the author's intentions: confessional, cathartic, educational, creative, mnemonic, reflective, and therapeutic are only some of the possible uses (Bagnoli, 2001). Despite the multiplicity of their formats and purposes, however, three basic types may be distinguished (Allport, 1942): the intimate journal, which is the most reflexive format; the memoir, a recollection of events made at some time distance; the log, the more impersonal record and listing of things. One further distinction, which applies to research, concerns whether diaries are spontaneously written or solicited by researchers.

3.3 Solicited diaries are most commonly used in time-use surveys, as well as in research on memory, personality, and dreams. These diaries typically have a fairly structured format, which would supposedly encourage people to be constant in their writing, by making it easier and quicker (Gibson, 1995). Another often found assumption is that diaries would suit an educated sample, because of the literary confidence required by writing. Zimmerman and Wieder, in their study on the American counterculture (Zimmerman and Wieder, 1977), designed an innovative way of researching with diaries, which I took as model for this study. Their diary, a log where people keep a record of their activities for a week, writing what they think significant in response to the formula who/what/where/when/how, is the basis for a successive interview. Guided by the diary entries, the interview probes, expands on areas of major interest, besides filling any gaps.

3.4 In the context of my research, some adaptations seemed necessary. The sample that I intended to study had a more mixed composition than either Zimmerman and Wieder's, or than that studied by Elliot in a more recent application of the diary-interview method (Elliot, 1997). Assuming anything general about participants was thus difficult, including their willingness to write, an issue often referred to as problematic, which was here made even more so by the absence of any financial reward. Further, the simple log format adopted in both Zimmerman and Wieder's and Elliot's studies did not seem sufficient to encourage the reflexivity I was after. A diary format that, while providing some framework to encourage writing, could still maintain enough of the flexibility peculiar to this medium so to work as a reflexive tool was therefore needed.

3.5 Through the introduction of an interview before the diary, and the addition of visual methods, the method eventually shifted from a purely diary-based approach to a more complex multi-dimensional methodology that not only maintained the flexibility of the diary, but actually widened it, complementing diary writing with other media.

The Multi- method Autobiographical Approach

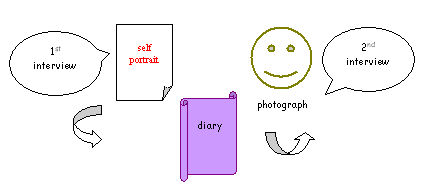

4.1 The multi-method auto/biographical approach that I designed has a longitudinal nature and centres around the production of the diary, which now serves as a link among the complex of instruments which compose it (Figure 1): a 1st interview during which participants are asked to produce a self-portrait; a one week diary which is kept starting on the day following the interview; a photograph of the participant; a 2nd interview, guided by the diary and all the rest of the materials collected in the research.

|

| Figure 1. The multi-method autobiographical approach |

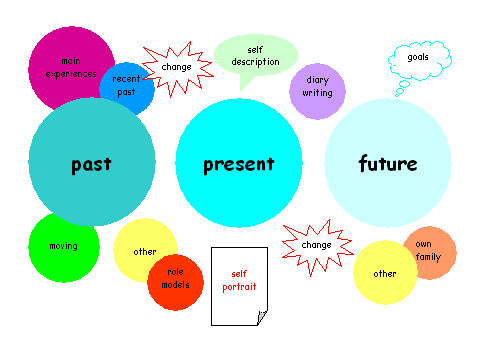

4.2 The 1st interview aimed to set diary writing in context, by familiarising participants with the areas of interest to the research. An open interview, it was organised around an agenda which is graphically represented in Figure 2.

|

| Figure 2. The 1st interview map |

4.3 The opening was a 'grand tour' (Spradley, 1979) request for a self-description, the response to which very much shaped the individual outline of each interview. Participants were asked to reflect whether their present description involved some change from their past, and how. The thematic sphere on past experiences inquired about those events that participants indicated as fundamental in their lives, both in a positive and in a negative sense, and both in relation to a distant and a more recent past. Migrants were asked about expectations about moving, an account of their experiences, difficulties encountered, and language use; the others about willingness to move from their present location. The thematic sphere relating to 'the other' inquired about most important people in participants' lives, as well as role models, drawn from both imaginary and everyday worlds. Participants were also asked to narrate instances in which they had felt to be in contrast with their social network. Diary writing was introduced by asking whether they had ever kept diaries, and by a request for a narrative of yesterday's events. Those who expressed concern at the task of diary writing were additionally asked to produce a one-page yesterday's diary at this stage, modelled on the research diary. Participants were then asked again about the important others in their lives and about any plans they had of having a family. They were encouraged to project themselves in the future, on a time-shift of ten years, and asked to reflect about their goals and aspirations. They were also asked about any aspect of themselves which they would like to change. Diaries were assigned at the end of the interview, with an instruction booklet and a verbal explanation of what was required.

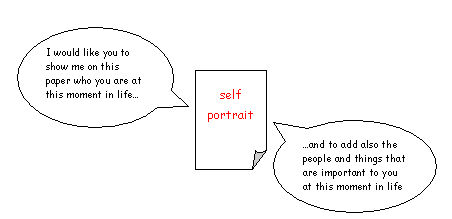

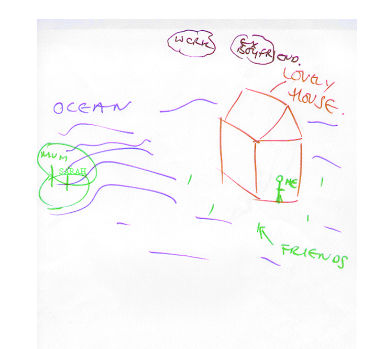

4.4 During the 1st interview, in order to encourage reflexivity, and to get to participants' own meanings of their lives, I employed a projective technique of my own design, the self-portrait. By being minimally structured, projective techniques allow respondents to impose their own form of organisation, bringing thus into expression their needs, motives, and emotions (Allen, 1958). Although they tend to be used mainly in clinical contexts, their employment may be fruitful also in other settings, where no pathology is presupposed. In more socially based research, it is not so much the drawing as such to constitute the data, but the whole context of production (Morrow, 1998). The self-portrait technique was introduced as a task-related 'grand tour' and consisted in presenting participants with paper and felt tips, asking them to show who they were at that moment in life, and then to add the people and things that they considered important at that time (Figure 3).

|

| Figure 3. The self-portrait |

4.5 The diary consisted of seven formatted pages, plus another seven blank pages as extra writing space. Each page was formatted with three prompts of a broad nature asking participants a daily record of: what they thought was the most important thing they had done; the people they had seen and spent their time with; and the people they had thought about, who might also not have been there with them. It thus asked for an account of their day which spanned between the factual and the imaginary. There were relevant spaces to be filled indicating the date and time of writing. Lines were ruled, on the assumption that such visual formatting would encourage writing.

4.6 The two-page accompanying booklet addressed participants individually, and made note of the method that would be used for diary collection and of the next meeting date. It gave guidelines for diary writing, underlining that prompts were intended to be general, and requested to write on a daily basis, or on the morning following the events at the latest. It also asked to refer to the self-portrait that had been drawn during the interview, if appropriate, and to enclose a photograph of the self. My contact address and telephone number were enclosed. Diaries were either collected by myself or returned by mail.

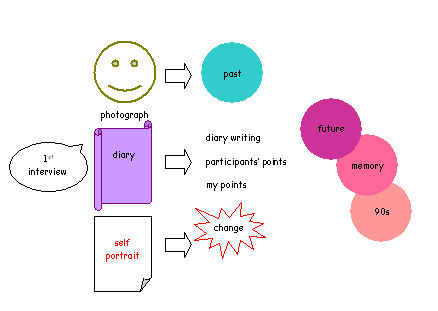

4.7 The 2nd interview was guided by all the material collected in the research, through the diary and other media. The diary-guided elements inquired on how participants had found diary writing, and on what they considered the main points they had written about, before exploring the points that I had highlighted myself. These points were further probed, together with all information previously gathered. Self-portraits were shown again and participants were asked whether they would now represent themselves in the same way or not. The photographs were the basis for further questions regarding the past context of their production.

4.8 As well as linking to the previously collected materials, the 2nd interview introduced a few more questions regarding the future. People were asked to imagine how they would like to represent themselves as a young person to a hypothetical child of theirs in the future, and then to provide another imagined memory of their youth, this time of a collective nature, specifying what events they thought they might remember about the present time. They were also asked to offer a definition of their generation of young people of the 1990s. The 2nd interview did not only probe the collected material, but also worked as an ongoing check on the data collection process, allowing me to include any item which might have slipped from the 1st interview agenda (Figure 4).

|

| Figure 4. The 2nd interview map |

4.9 In order to collect a holistic description of young people's lives, I widened the research to the use of photographic data, asking participants to include in their diaries one photograph of themselves that they particularly liked. The photographs that I collected in this research, having been spontaneously taken for private use, fall into the category of the 'home mode' (Musello, 1979). The naïve production of photographs usually follows patterns that are often unclear to photographers themselves, since they are inscribed in the more general representational codes of society. Home mode photography is not documentary in approach, and usually edits out everyday contexts as well as negative and painful events from the records of one's life (Spence and Holland, 1991). These photographs were the basis for further questioning in the 2nd interview which concerned the context of their production, the memory of the particular events portrayed, the reasons behind the choice of that particular photograph, and any other point which appeared relevant, in relation to the themes raised.

A Holistic Picture of Identities

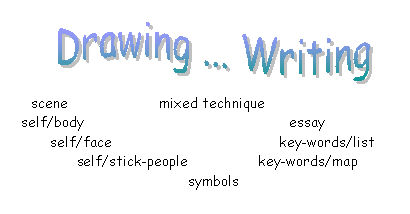

5.1 The fieldwork study for this project was conducted in Italy and in England, in the Provincia di Firenze and in Cambridgeshire respectively, and lasted from late February 1998 until early October 1999. 41 young people from a variety of backgrounds took part, accessed through multiple routes and selected through a process of theoretical sampling, on the basis of the intersection of the characteristics of age, sex, and nationality with the case study theme of migration. Aged between 16 and 26, they were equally divided between men and women, English and Italians, migrants and locals. The migration considered was between Italy and England, was defined as first generation, and had a time frame of at least 6 months.

5.2 The autobiographical framework of the research was provided by taking as a reference point my own life experience of migrating from Italy to England as a young woman. Sharing the identity of the migrant was a crucial component of the relationship which in each single case was established between the subjectivities of the participants and mine. However, other identities of mine will have been salient to establish rapport in other cases, for instance being a woman, a student, a university researcher, and a psychologist. Since participation relied on volunteering, the only reward that these young people could possibly aim to achieve was to hopefully learning something about themselves, thus their keen involvement is worth mentioning as one result in itself. The study, being longitudinal, required in fact a considerable amount of time and effort on their part, as well as some degree of consistency in the task of keeping a diary.

5.3 Circumstances of access, together with specific interests connected with the research issues, especially the England/Italy theme, were important in shaping the character of the young people's involvement. However, autobiographical experiences were the main issue regulating participants' own agendas. Whenever they would be going through a period of their lives which for some reason had heightened their reflexivity, there was an easy convergence between the young people's own and the research agendas, given that promoting self-reflection was one of the main aims of the study. This was the case with Emma[2], who had just realised that she wanted to change jobs, and with Michelangelo, who had just started seeing a psychotherapist. The ways in which these young people perceived me and related to me was fundamental in shaping their agendas and understandings of the research.

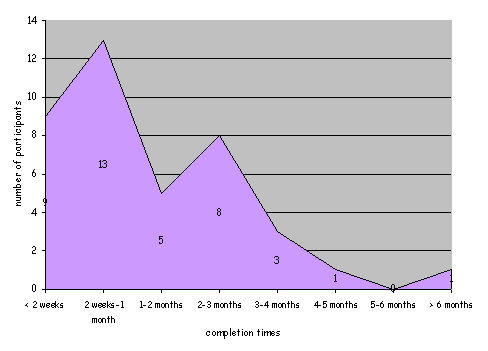

5.4 A longitudinal study offers the possibility to witness participants change over time, thus making it possible to study processes whilst also retaining a dynamic image of people. For most of these young people the time interval covered by the research was within three months, with the majority being involved on a time scale between two weeks and one month (Figure 5).

|

| Figure 5. The research completion times |

5.5 It was to emerge in the field that when the interval stretched for longer than planned, the method seemed to acquire in insight, and the 2nd interview in particular granted much richer data. Longitudinal change in the sample was in part associated with relationships, exams, and employment. As far as relationships are concerned, changes went both in the direction of developing and establishing a relationship, and in the opposite sense, of breaking it. Exams and other tests were part of the daily life of students, some of whom would be going through crucial stages of their academic careers, sometimes actually in the process of taking exams. For other participants it was possible to witness a change in their attitudes towards their job, including cases in which occupational mobility was considered.

Participants' Response and Analysis Procedures

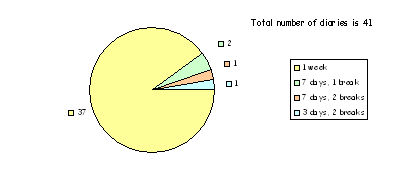

6.1 The young people responded enthusiastically to the use of these combined methods and indeed their active involvement made the project an extremely pleasant and rewarding experience. Contrary to what indicated in the diary literature, writing was not a problem for these young people. This clearly emerged quite early on in the fieldwork, and made me abandon my early plans of carrying out routine telephone checks and mid-week diary collections in order to encourage writing. Only four participants did not keep the diary according to instructions, writing only for three days in one case, or for seven non-consecutive days, the remaining three (Figure 6).

|

| Figure 6. Diary writing times |

6.2 It is worth pointing out that those four participants who were less consistent in their writing happened to be students: the young people who according to the literature would supposedly be less used to and inclined to writing resulted in fact to be more conscientious with their task.

6.2 By means of the detachment which writing introduced, diaries were sometimes able to register information that would not easily have found expression otherwise. Carlo, a 21-year-old student, so wrote in his diary: On my way back, maybe because I was thinking about the diary that I would have to write, I thought about one important person that I forgot to mention in the interview, my grandad. It is 4 years already that my granddad is no longer here, and I must say that I often happen to think of him, despite the years. Granddad would deserve an entire chapter, but this is only a diary (...) Anyway, I thought about granddad, and I have always thought that he can see me and hear me. Whereas I do not think that of other people that have died. I have thought about the luck that I have had that he left me with so many beautiful memories, and about how much he has taught me, and I felt a bit guilty about leaving him out of the list of 'role-models' in the interview. 5/3/9

6.4 It is perhaps no chance that the memory of his granddad only surfaced later in Carlo's diary: many emotions are attached to it, and it would not have been easy to deal with them in the interview. Diaries may allow a suitable time and place for data that are too emotionally charged and may be regarded by participants as sensitive and too private.

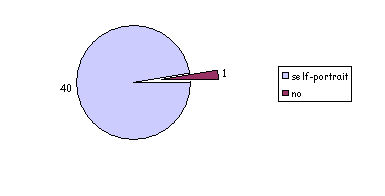

6.5 All participants produced a self-portrait (Figure 7), with the exception of Gianna, a 20-year-old student who rejected this technique with these motivations:

|

| Figure 7. Participants in self-portrait technique |

6.6 In denying her ability to 'codify' herself, Gianna is also resisting the idea that the research itself would ultimately be able to define her. By choosing to leave the paper blank she is thus asserting her own voice as discordant with the research framework, reclaiming authorship over her biographical narrative. In most cases, however, the self- portrait helped 'breaking the ice' during the interview (Morrow, 1998), making people feel more comfortable. The self-portrait drawn by Emma, a 26-year-old English woman, is a good indication of the strength that may be achieved by this method (Figure 8).

|

| Figure 8. Emma's self-portrait |

6.7 Drawing the self- portrait helped Emma identifying and representing what was going on in her life at the time, making it easier for her to communicate feelings and aspirations on areas that were currently sensitive. The drawing is highly revealing, and in a way in which words sometimes cannot be. This is one case in which the self-portrait was able to condense the participant's own insight on the life stage which she was currently living. At the analytical level, this condensing effect of self-portraits was extremely useful.

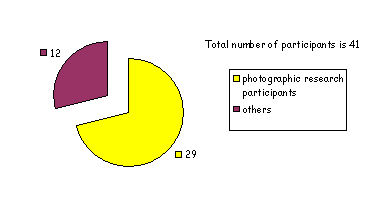

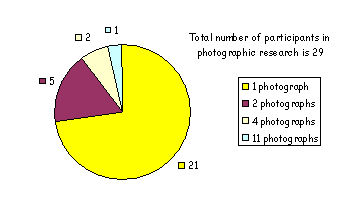

6.8 Twenty-nine of the participants became involved in the photographic research (Figure 9).

|

| Figure 9. Participants in photographic research |

|

| Figure 10. Number of photographs |

|

| Figure 11. Emma's photograph |

6.9 In this photograph, Emma is sitting in Piazza della Signoria, in the very heart of Florence, having white wine, actively enjoying what best the city she has moved into has to offer. This image conveys a Grand Tour narrative which clearly indicates Emma's love for Florence, as well as her happiness at having made of Florence her home, despite the current difficulties she is experiencing in her life (Bagnoli, forthcoming 2004).

6.10The totality of these multi-level autobiographical narratives were jointly analysed according to the criteria of qualitative narrative analysis (Lieblich, Tuval-Masiach, and Zilber, 1998). The analytic process developed dialectically, making constant reference both to the theoretical framework and to the ongoing process of data generation, with particular attention to participants' own input in individuating and explaining the research issues. In reading these data, all of the four analysis modalities that Lieblich et al (1998)indicate from the intersection of the two main dimensions of holistic/categorical and form/content were applied, at different moments. The holistic/content approach, which focuses on the themes of narratives, was most useful when first reading the material, as well as when transcribing, since it allowed a general overview of what was present in the data. The holistic/form perspective, which looks at the formal aspects of narratives, borrowing its tools from literary theory, was applied to make a structural reading of life stories which helped delineating moments of transition, signalled both by answers to specific questions and by the participants' own use of terms such as 'turning point'. The categorical reading of data was greatly eased by the use of the Atlas-ti computer package (Muhr, 1994). When focusing on content, this fine reading of material was made in relation to specific topics being scrutinised. When focussing on form, it was on the basis of the expressive styles, rhetorical images, and multiple voices appearing in the text that the data was scanned.

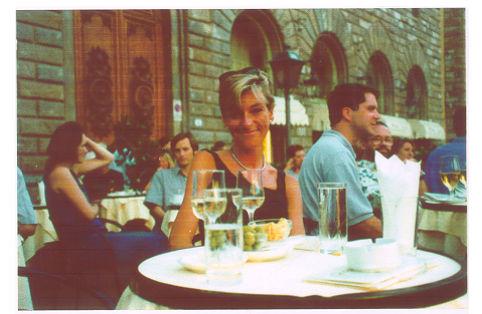

6.11 Self-portraits were considered primarily in connection to the 'grand-tour' question (Spradley, 1979) to which they were related, for the extent to which they enabled participants both to graphically represent the points they were making, and to widen the discourse as well. They were classified according to the style of their production, which led to trace a continuum going from drawing to writing, which is illustrated in Figure 12.

|

| Figure 12. The self-portrait styles' continuum |

6.12 'Home mode' photographs were analysed by looking at who were the participants, where the photographs were set, and what topics or narratives were being told. The context of production and the kind of interaction going on between photographers and subjects was also taken into account, and with it, the resulting style of self-presentation: whether idealised and formal or naturalistic, as well as the extent to which people were posing, or had ironic or self-parody intents (Musello, 1979). Other elements were scrutinised, and notably instances where people were smiling, touching, appeared in groups, were located indoors or outdoors, or portrayed themselves through relational stories or achievement stories, through codified rites of passage, or through the travel photograph genre (Dollinger, Preston, Pagany O'Brien, and DiLalla, 1996;Ziller, 1990).

6.13 The insights gathered from visual documents were sometimes extremely helpful in that they were able to represent concepts in a particularly condensed and poignant manner. However, visual data were always considered in context with the rest of the materials, as different parts pertaining to the same whole. Throughout the analysis, efforts were made to establish links between documents of different type, so as to test and validate any emerging interpretation through recurrence across multiple sources. On this purpose, the use of the Atlas.ti computer software proved particularly useful, because of the possibility it offered of joining material coming from different sources under the same code. Another specific feature of Atlas.ti, the option of drawing networks, was an excellent way of brainstorming and clarifying ideas through a visual and flexible representation of the multiple connections existing among different elements.

Conclusions

7.1 In designing the autobiographical methods for this research, three were my main aims. Firstly, I wanted to appreciate the dialogical dimension of identities through encouraging participants to be reflexive about their lives. Secondly, I aimed to be sensitive to the young people's own ways of expressing themselves, so that they might take part in the research according to their chosen modalities. Thirdly, I intended to promote participants' active involvement as co-researchers in guiding me through their lives. The multi-method autobiographical approach that I designed on the basis of Zimmerman and Wieder's model proved excellent on all three purposes. The level of reflexivity that this methodological approach achieved is well indicated by the richness and quality of the data that it allowed me to gather. The openness of its structure also meant that participants were indeed able to direct the research according to how they wished. The young people's lead was followed at the levels of sampling, data collection, and emerging analysis as well, the agenda of the 2nd interview in particular directly arising from the context of the diaries that they had written.

7.2 Perhaps the main strength of the approach lies in the flexibility with which, thanks to its composite nature, it was able to stretch and adapt to the different needs and expressive styles of the young people involved. Whether more comfortable with words or images, talking or writing, these methods effectively put the young people in the position of making the research reflect their own identities. This flexibility extended to the researcher as well in that it allowed me to try other ways to record information, whenever some route would prove problematic. Such sensitivity for the subjective worlds of participants perhaps also implied, at the analytic level, favouring a consideration of these narratives as individual cases, rather than their comparison across patterns and larger units.

7.3 The young people showed great appreciation for this composite approach, enthusiastically participating in the study. Diary writing presented hardly any problems, both as a format and in terms of consistency, and was in fact much appreciated. Both interviews were very thorough and the balance between them showed that, when the longitudinal span they covered was longer, the passing of time introduced an element of dynamism that made the previously gathered data acquire in depth through the comparison. Adding a visual component to the research was also beneficial. The self-portrait often had an 'ice breaking' effect, helping people feel more at ease during the interview, although it occasionally had an opposite effect as well. Photographs and self-portraits were a helpful source of information regarding the identities that were crucial to the young people at that moment, and their immediacy of insight was precious during the analysis.

7.4 In sum, the results achieved by these methods gave a very positive response to my idea of widening the range of autobiographical tools to the use of visual and written sources. The combined use of these alternative forms of data collection could achieve a high level of flexibility, often accessing information which might have been difficult to gather with the use of the sole interview.

7.5 From an epistemological point of view, the autobiographical character of the project made of the interplay of my own subjectivity with the subjectivities of the young people involved a fundamental trait which was present throughout all stages of the research process, from the definition of parameters to data collection and analysis as well as the production of results. By choosing a research sample partly composed of young people who, like myself, had had some experience of migrating between England and Italy, I was able to capitalise on the inter-subjective nature of the research, making reference to my own autobiography to appreciate the life-stories which I was collecting. The relationships that I was able to establish with each of these participants, in the context of the specific life circumstances which they were living at the moment, shaped the research, the modalities, and the quality of their involvement. Sharing the identity of the migrant made it possible for them to relate to me on the assumption that their experiences would mean something to me. Indeed, it often made them interested in knowing my own story too.

7.6 This dialogue between subjectivities, of the participants' and mine, which the research promoted, had implications for our respective lives. Through the narrative reconstruction of one's own autobiography, this project was encouraging a reflexive attitude and also aiming to become, when possible, an instrument of self-scrutiny and change for the young people taking part. The enthusiastic and highly appreciative quality of these young people's involvement indicated not only their enjoyment of the research, but in some cases also corresponded to an effective empowerment that they achieved over their lives. Whenever the circumstances of their lives had required them to be more reflexive, the research offered them an extra dimension on which to carry on that ongoing reflection. The longitudinal nature of the approach, while recording a dynamic view of their identities, also incremented their awareness of the changing circumstances of their lives. On my own side, by engaging with these young people and listening to their own stories of growing up, I was able to compare their individual routes through young adulthood and migration to my own personal experiences, and in so doing acquire a novel account of my autobiography as well. As a result, this project was a learning experience for both the participants and the researcher, which allowed the investigation of subjectivities in a mutual dialogue on multiple levels (Stanley, 1992).

7.7 This aspect of intervention on people's lives poses a series of questions from an ethical point of view which are central to autobiographical research as a whole. When a trusting relationship has been established between researcher and participant, people easily disclose their lives far more than they originally might have intended to and, quite likely, also information of a sensitive nature. However, once the interview is over, they may be left with contrasting feelings and in a condition of emotional vulnerability for the power they have attributed to the researcher, who may even be viewed as a therapist. This is what happened with Michelangelo, a 26-year-old engineer, who, having just started psychotherapy at the time of the study, interacted with me on the assumption that I was an all-knowing psychologist. Even though I had made clear to him the aims and context of my research, his own agenda still shaped the interaction considerably. Michelangelo's case is indicative of the complexity of power relationships involved in autobiographical research, as well as of the ethical implications of such work. He constructs the research as akin to a therapeutic setting, according to his own needs and desire to be listened to. This motive may often draw people to participate in research and is not so dissimilar from what makes someone decide to engage in therapy (Miller, 1996). Narrative and autobiographical research may indeed have several points of convergence with therapy. However, the researcher/participant relationship is not regulated by the same rigorously spelled out codes which distinguish the therapist/client one (Lieblich, 1996). It is thus very important to be aware as researchers of the possible implications of our intrusion into people's lives (Josselson, 1996), as well as of the complex power relationships we may become entangled in with our work (Lieblich, 1996). The relationships that we develop in the field may occasionally prove problematic, especially if one gets attributed some 'special' role. While being sensitive to participants' needs, it is important to be clear in distinguishing one's own role as a researcher from any other projected roles. In Michelangelo's case, however, despite my attempts at clarifying my position as researcher and not therapist, his own construction of myself actually stayed as such, regardless.

7.8 In a number of ways, this research made it possible for participants to be fully involved as authors of their own autobiographies. At the level of data collection, the open and participatory nature of the research did allow the young people to contribute as much or as little as they wanted in the ways which they found most congenial. They could effectively express their own insights over what they considered important in the process of defining an identity in the contemporary world. However, in the later stages of the research, at the level of data analysis, I was the sole author of the organisation and interpretation of their own insights. I hope that this detailed account of the methodology that I adopted may be a good indication of the process of analytic reflexivity (Stanley, 2000) which I maintained in my work, and that the procedures taken and the choices made throughout the various stages of the project may here appear transparent and accountable as it is appropriate in a context of qualitative inquiry (Bauer and Gaskell, 2000).

7.9 One concluding note concerns some unintended consequences that this research had on the lives of participants, as well as on mine. Having developed out of my own interest in diary writing, this study encouraged several of the young people to keep diaries in their everyday lives. By contrast, I found that, as I progressed in the field, my diary writing became rarer. Throughout these years I have been living through the words and diaries of others, rather than my own, and paradoxically, after caring so much to encourage writing, the less consistent of diarists eventually turned out to be the researcher herself.

Notes

1 This research was funded by an EC Marie Curie Fellowship.

2 All names are fictional, and have been chosen by participants themselves.

3 Bella casa = beautiful house.

4 Emma gave written consent to publication of her photograph.

References

ALLEN, R. M. (1958) Personality Assessment Procedures. New York: Harper and Brothers.

ALLPORT, G. W. (1942) The Use of Personal Documents in Psychological Science. New York: Social Science Research Council.

BAGNOLI, A. (2001) Narratives of Identity and Migration: an Autobiographical Study on Young People in England and Italy. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Cambridge.

BAGNOLI, A. (forthcoming, 2004) 'Constructing the hybrid identities of Europeans', in G. Titley (editor) Resituating Culture. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

BHABHA, H. K. (1994) The Location of Culture. London: Routledge.

BRUNER, J. (1990) Acts of Meaning. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

CAGLAR, A. S. (1997) 'Hyphenated Identities and the Limits of 'Culture'', in T. Modood and P. Werbner (editors) The Politics of Multiculturalism in the New Europe. London: Zed Books, pp.169-185.

DOLLINGER, S. J., PRESTON, L. A., PAGANY O'BRIEN, S. and DI LALLA, D. L. (1996) 'Individuality and Relatedness of the Self: an Autophotographic Study', Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 71, No. 6, pp.1268-1278.

ELLIOT, H. (1997) 'The Use of Diaries in Sociological Research on Health Experience', Sociological Research Online, Vol. 2, No. 2, <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/2/2/7.html >.

EVANS, M. (1999) Missing Persons: the Impossibility of Auto/biography. London: Routledge.

GASKELL, G. and BAUER, M.W. (2000) 'Towards Public Accountability: beyond Sampling, Reliability and Validity', in M.W. Bauer and G. Gaskell (editors) Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound. A Practical Handbook. London: Sage, pp.336-350.

GERGEN, K. J. and GERGEN, M. M. (1988) 'Narrative and the Self as Relationship', Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 21, pp.17-56.

GIBSON, V. (1995) 'An Analysis of the Use of Diaries as a Data Collection Method', Nurse Researcher, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp.66- 73.

GIDDENS, A. (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

HERMANS, H. J. M. (2001) 'The Dialogical Self: Towards a Theory of Personal and Cultural Positioning', Culture and Psychology, Vol. 7, No. 3, special issue: Culture and the Dialogical Self: Theory, Method and Practice, pp.243-281.

HERMANS, H. J. M., RIJKS, T. I. and KEMPEN, H. J. G. (1993) 'Imaginal Dialogues in the Self: Theory and Method', Journal of Personality, Vol. 61, No. 2, pp.207-236.

JOSSELSON, R. (1996) 'On Writing Other People's Lives: Self-Analytic Reflections of a Narrative Researcher', in R. Josselson (editor) Ethics and Process in the Narrative Study of Lives, Vol. 4. London: Sage, pp.60-71.

LIEBLICH, A. (1996) 'Some Unforeseen Outcomes of Conducting Narrative Research With People of One's Own Culture', in R. Josselson (editor) Ethics and Process in the Narrative Study of Lives, Vol. 4. London: Sage, pp.172-184.

LIEBLICH, A., TUVAL-MASIACH, R. and ZILBER, T. (1998) Narrative Research: Reading, Analysis and Interpretation, Vol. 47. London: Sage.

MARKUS, H. R. AND NURIUS, P. (1986) 'Possible Selves', American Psychologist, Vol. 41, No. 9, pp.954-969.

MILLER, M. E. (1996) 'Ethics and Understanding Through Interrelationship: I and Though in Dialogue', in R. Josselson (editor) Ethics and Process in the Narrative Study of Lives, Vol. 4. London: Sage, pp.129-147.

MORROW, V. (1998) 'If You Were a Teacher, It Would Be Harder to Talk to You: Reflections on Qualitative Research with Children in School', International Journal of Social Research Methodology. Theory and Practice, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp.297-313.

MUHR, T. (1994) Atlas.ti (Version 4.1). Berlin: Scientific Software Development.

MUSELLO, C. (1979) 'Family Photography', in J. Wagner (editor) Images of Information: Still Photography in the Social Sciences. London: Sage, pp.101- 18.

NEISSER, U. (1982) (editor) Memory Observed. Remembering in Natural Contexts. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company.

PAASI, A. (2001) 'Europe as a Social Process and Discourse. Considerations of Place, Boundaries and Identity', European Urban and Regional Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp.7-28.

PLUMMER, K. (2001) Documents of Life 2: an Invitation to Critical Humanism. London: Sage.

SMITH, S. (1993) 'Who's Talking, Who's Talking Back? The Subject of Personal Narrative', Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp.392-407.

SPENCE, J., and HOLLAND, P. (1991) Family Snaps: the Meanings of Domestic Photography. London: Virago.

SPRADLEY, J. P. (1979) The Ethnographic Interview. London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

STANLEY, L. (1992) The Auto/biographical I. The Theory and Practice of Feminist Auto/biography. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

STANLEY, L. (1993) 'On Auto/Biography in Sociology', Sociology, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp.41-52.

STANLEY, L. (2000) 'For Sociology, Gouldner's and Ours', in J. Eldridge, J. MacInnes, S. Scott, C. Warhurst and A. Witz (editors) For Sociology: Legacies and Prospects. Durham: Sociologypress, pp.56-82.

STANLEY, L. and WISE, S. (1993) Breaking Out Again. Feminist Ontology and Epistemology. London: Routledge.

WATSON, J. (1988) 'Shadowed Presence: Modern Women Writers' Autobiographies and the Other', in J. Olney (editor) Studies in Autobiography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.180-189.

ZILLER, R. C. (1990) Photographing the Self. Methods for Observing Personal Orientations. Newbury Park, California: Sage.

ZIMMERMAN, D. H. and WIEDER, D. L. (1977) 'The Diary. Diary-Interview Method', Urban Life, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp.479-499.