by Alice Altissimo

Hildesheim University, Germany

Sociological Research Online, 21 (2), 14

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/21/2/14.html>

DOI: 10.5153/sro.3847

Received: 13 Nov 2015 | Accepted: 26 May 2016 | Published: 31 May 2016

This paper reveals the potential which lies in combining the qualitative analysis of egocentric network maps with the corresponding narratives collected simultaneously during an interview. It presents a method of analysis which has been validated in research on the lifeworlds of international students in order to elucidate their perspective on social support in their everyday lives. It is a method of analysis which can be applied in various other research fields and to answer various research questions when it comes to exploring meanings, feelings, relationships, attractions, and dependencies. The method is interviewee-centred and the approach is holistic, leading to comprehensive insights. Using examples of original research data, this paper first illustrates the data collection and then the data analysis procedure in the following three steps: analysis of the map, analysis of the narrative, and combination of the analyses.

1.1 This paper presents a method to qualitatively analyse data in the form of network maps and narratives collected simultaneously during an interview. One basic understanding of this article is that in social network analysis, we cannot focus on network structure to the exclusion of network content. This is in accordance with Ryan & Mulholland (2014): 'In exploring the meanings that participants attach to social ties, it is useful not only to record how networks are spoken about in interviews, but also represented through visual images.' (p. 2) When it comes to research about interpersonal topics especially (e.g. transnational migration issues), McCarty (2007) endorses personal network visualisation because it is a unique means of gathering information on the network perspective. Although network maps are currently being used in numerous studies and in different variants, they are most often used to provide a complementary picture. Due to a lack of an elaborated method in network research to qualitatively analyse the visualisations of personal networks, visualisations themselves are seldom analysed as such, or are looked into only to verify the analysis of the narrative. In some cases maps are created from a narrative and then analysed quantitatively, which is a plausible approach to analysing the visualisation, but again a quantitative one. Instead, the method of qualitative analysis of network map interviews discussed here considers the map itself as a self-standing set of qualitative data, just as relevant as the narrative, and analyses it as such. Both sets of data were collected simultaneously and are therefore closely intertwined, but the analysis of each set singularly, aims at gaining additional insight into underlying meanings. The paper will illustrate such an analysis of a network map and an interview by following a recently introduced qualitative approach for network analysis. Herz et al. (2015) provide a comprehensive description of a procedure which they call Qualitative Structural Analysis (QSA): QSA combines analytical perspectives of structural analysis from SNA and analytical standards taken from qualitative social research by introducing qualitative procedures (sequential analysis, sensitizing concepts, memos) to analyse network maps and narrative data (Herz et al. 2015; Peters et al. 2016; Truschkat 2016). This paper focuses on three steps of the analysis procedure deduced from QSA: analysis of the map, analysis of the narrative, combination of the analyses. They will first be described and then applied to data from an interview with an international student.

2.1 The study at the basis of this article explores international students' perspectives on social support in their everyday lives. The sample was made up of fourteen students who were studying abroad on diverse courses in Germany or Canada in 2012 and aiming to obtain a degree there. The main interest of the study was the relationships in the students' everyday lives and their perception of these relationships, e.g. as supportive or inhibiting to them. The aim of the study was to gain insight into their understandings of support and their strategies in their everyday lives as international students. Due to this research focus, it was opportune to opt for a qualitative network analysis, since in general, qualitative analysis is appropriate when subjective meaning and perspectives are to be explored as well as practices of the construction of reality (see Flick et al. 2004: 3ff.). Such methods of analysis enable an explorative procedure to be used: the data collection is designed in a non-restrictive manner to include the collection of unexpected understandings and theories on social reality. Further, an inductive analysis of the data seeks to generate new theories based more on the empirical material and less on pre-existing theories. More specifically, when regarded as social entities, networks can also be analysed to research into relationship patterns and social structures. Although social network research is dominated by quantitative research methods, qualitative methods are also fruitful and valid approaches when the intention of the investigation is less to verify and more to generate hypotheses. In her overview of qualitative approaches in Social Network Analysis, Betina Hollstein makes a case for qualitative research methods, stating that they 'offer special tools for addressing challenges faced in network research, namely to explicate the problem of agency, linkages between network structure and network actors, as well as questions relating to the constitution and dynamics of social networks' (Hollstein 2011: 404). The potential of qualitative research in social network analysis is unquestionable and is gradually being unfolded. There are various areas in which qualitative approaches contribute to network studies. Hollstein identifies six such areas: 'exploration of networks, network practices, network orientations and assessments, network effects, network dynamics, and the validation of network data' (ibid. 406). The study on international students which this paper draws from can be localised in the area of network orientations and assessments, an area which deals with aspects such as belongings, loneliness, patterns of migrants' integration into networks and their network strategies. Other areas are also touched upon in the underlying research: the question of network effects, for example, arises when discussing how students' relations affect their decisions to move; network dynamics also become relevant when the students identify the changes in their networks over time.

3.1 To be able to understand the analysis of the data it is relevant to understand the process of data collection. The method of data collection used in the study underlying this paper connects narrative interviews with the visualisation of the respondents' network. Such combinations are seen as increasingly interesting, among other things because visualising and graphically representing personal networks strongly supports their description in the narrative (cf. Schöhnhuth 2013). It helps both the interviewer and the interviewee keep track of the relationships discussed in qualitative interviews which are specifically designed to collect interviewees' systems of relevance and modes of behaviour. Combinations of narration and visualisation are appreciated in various research fields, e.g. in health and fertility research (Tubaro et al. 2013; Keim et al. 2009), in transnational family research (Bernardi 2011), and in migration research (Herz & Olivier 2012). Depending on the fields, variants of the combination of narration and network visualisation have been deployed and are used to collect data in different ways for different purposes: to visualise certain aspects of the narration, to generate a narrative from the visualisation, or to use the visualisation as a structuring element for the narration. The method discussed here collects the narrative at the same time as the visualisation and is an adaptation of the concentric circles used by Kahn and Antonucci, the central circle being the ego (in this case the respondent), as in the following figure:

|

| Figure 1. Network map (adapted from Kahn and Antonucci 1980). |

3.2 The map was presented to the interviewees at the beginning of the interview and was used as a pen-and-paper visualisation. The interviews lasted over two hours, during which the student talks about various alters who are currently or who have been important to her in various situations. Additional questions in the interview guide encompassed topics such as mobility, communication with alters, organisation of the studies abroad and future plans. Further details about the name generator used will be provided below.

3.3 Known as target sociograms, such maps vary in the degree to which they are prestructured, e.g. the number of circles they feature or the inclusion of segments corresponding to various social contexts (e.g. family, friends and work). Hollstein and Pfeffer (2010) provide an overview of the spectrum of sociograms from which to choose: unstructured maps, structured maps and structured and standardised maps. They explain the various types of applications for each type, their benefits and drawbacks. For this study, the pre-test phase showed that a kind of map should be chosen which allows enough subjectivity and standardisation at the same time for the interviewee to depict their network quite freely, while still offering them a certain degree of guidance.

3.4 Another important decision which was taken before the data collection concerned the question of whether the network should be visualised using a pen-and-paper method or supported by computer programs. Since digitalisation more easily entails standardisation, a pen-and-paper method was chosen for this study to keep the procedure intuitive and explorative. Hogan et al. (2007) recommend that visualisation using computer programs should be used in the lab, and low-tech settings should be used in the field. Ryan et al. (2014) offer a detailed reflection of the advantages and disadvantages of the different kinds of visualisation as well as a review of the literature on the topic. The author's own experience has shown that the pen-and-paper technique adopted for this study proved to be simple, intuitive and safe, since it did not need any technology nor a power supply, could not crash, be mistakenly deleted or left unsaved, as might be the case when using computer programs. The decision was also taken based on the experience that some respondents are reluctant to use computers and programs needed for such visualisation, whereas writing and drawing on a sheet of paper is a familiar activity to almost anyone. Although the pen-and-paper technique chosen here and presented below proved to fit well to the research question and the methodology of the study, computer programs fulfil quite different functions and therefore need to be considered separately, in the context of the respective study. In an article about precisely this topic, Olivier (2013) discusses the advantages and disadvantages of both survey methods, depending on the varying settings in which the research takes place and on the target group. She also makes a case for using additional pen-and-paper methods in situations ideal for digital data collection, because the two methods can complement each other in a fruitful manner.

3.5 One example of the method of data collection used here is the data gathered in an interview with an international student. The interviews conducted for the study begin with the interviewer explaining that the main interest is the student's current life and with a short explanation of the map's role in the proceedings. After an introductory question about the student, the interview focuses on important alters - other entities apart from ego - in her life. At this point, immediately after the introductory question, the map is introduced by asking the respondent to name people who are currently important to her and to place them along one border of the map. This procedure, the so-called name generator, can be shaped in various ways by varying the question asked to elicit names of people important to the respondent. For example, they may be asked to name people they talk to about specific topics, people they interact with frequently, people they are connected to virtually or people they would ask for a favour. Bidart & Charbonneau (2011) provide an introduction to different types of name generators in the first few sections of their paper, while Marsden (1990) and Herz (2012) discuss the use of name generators and interpreters in network research. Name generators are another highly sensitive issue, since they are the primary influence on the recollection of alters when recreating the network. A network recreation of this kind need not necessarily involve its visualisation. In this specific study the generator entails both the narration and the creation of a network map. The name generator used here asks for currently important alters in the respondents' lives by first asking about important people. Further on, as the interview proceeds, the respondents are also asked about other alters which play a role in their life, e.g. important places, ideas, situations, activities etc. This further prompting for alters is designed to include things, contexts, organisations or anything which the respondents miss and have therefore not listed. Often, various entities of this kind are made relevant by the respondents during the interview and the interviewer can pick up on them and ask the respondent to place them on the map, if they have not yet done so. The interviewer can then ask them to discuss these entities in connection to the other alters, too. For example, an interviewee mentions their job as something which is currently very important or discusses it at length. If they have not yet positioned 'job' on the map, the interviewer may want to ask them to do so and then ask them to describe how 'job' connects to the other alters on the map, what it does to the map and what this means to them. At this stage, the interviewer can also ask about alters which the respondent is in conflict with. Such difficult connections can also be quite important because they may influence not just ego but other ego-alter or alter-alter relationships, too.

3.6 As can be seen from the description above, the name generator used is based on a simple first invitation to name important people and then runs through the whole interview, in order to include various kinds of entities in different contexts. For this study it was also important to break up the way in which people tend to recall their alters because 'memories and information are not stored randomly, but arranged in hierarchical sets' (McCarty 2007: 158). Therefore, when asked to list their important contacts, people tend to mention alters from the same social context, thus recreating the social structure of their memory more or less accurately. By asking about entities as alters, missing or conflictual alters, social contexts can be crossed, combined or dismissed.

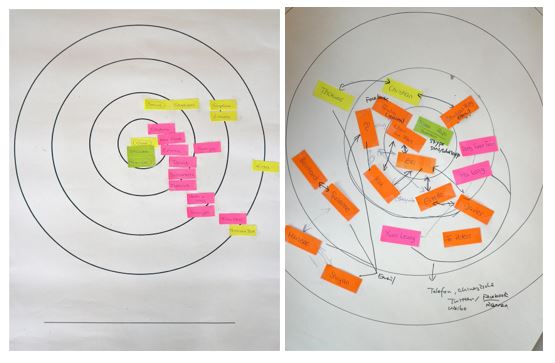

3.7 Having named the alters, the interviewee is asked to write them on sticky notes of a colour of their choice and to place them on the map closer to or farther from ego, according to their importance in their everyday life. The respondent is then asked to explain why the alter is important and to describe the relationship between themselves and the alter in question. Finally, the narration is directed towards relationships between the alters to collect a description of the contents and contexts of the alter-alter relationship and the relationship's meaning to the interviewee. The following are two examples of completed network maps.

|

| Figure 2: A.K., network map; Figure 3: S.L., network map |

3.8 Depending on how the interviewees respond, in some such interviews, the alters are all listed at the beginning and then described one after the other. In other interviews, the interviewee starts describing one alter and their relationship immediately, then goes on to name and describe the next alter. In others still, the interviewee first lists and describes only a few alters and then adds various others as they come to mind. During the interviews in this study, the order of the mentioning followed the interviewee's logic and varied depending on their priority-setting.

3.9 It is important to note that the data in the map and the narration are gathered simultaneously: while talking, the interviewee writes the sticky notes. While positioning them on the map, the interviewee reflects upon and explains the respective position and therefore the alters' importance to them and between one another. While discussing the alter-alter relationship, the interviewee highlights some connections, e.g. using arrows, lines, circles etc. This simultaneity of data collection lies at the basis of the assumption that the two sets of data are of equal value to the analysis. After a short insight into the respondents' reactions to the interviews, the method of analysis will be presented in chronological order.

4.1 Although the respondents had not been informed in detail about the interview including a network map as a visualisation technique, they all reacted with curiosity to its introduction. Having been given a set of sticky notes of four different colours to choose from freely and pens to write with and draw the connections, they quickly understood what they were invited to do and willingly worked with the map. Its optical and physical presence and its introduction at the beginning of the interview gave the map an important role throughout the interview; it actually usually became the golden thread of the narration, creating a situation in which the role of the interviewer's questions was to keep the respondent interacting with the map, more than with the interviewer. In their revealing paper about network visualisation and qualitative interviewing, Ryan et al. (2014) mention this shift of power relations, too. They also mention numerous other findings which this study endorses: the respondents' interest and enjoyment in creating their map due to the personal insights they could draw from it; the uneasiness in some when they had the feeling they were expected to 'grade' their alters or when they forgot someone important; the shift in some maps from ego to couple perspective; the attempts at depicting dynamism in the maps; and a general willingness to talk about and engage with their network on the map. For the interviewer the map was an aid to keep up a fluent narration, by allowing questions about alters, connections and other elements in a natural manner as they were being laid out on the map. It also facilitated questions concerning specific ties or constellations: during the conversation the interviewer could easily ask about alters in a particular position on the map (e.g. very far away from all the other alters) or about a particular constellation (e.g. two connected dyads) and learn more about these relationships, their meaning to the respondents and their effect on the network.

5.1 The analytical approach presented here is based on the following fundamental understanding: although structure is usually placed in the context of formal network analysis, as pointed out by Diaz-Bone (2007) in his review essay on whether qualitative network analysis exists, it is also instructive to consider structure using qualitative methods. Herz et al. (2015) provide a comprehensive description of a procedure for this kind of Qualitative Structural Analysis: their instructions on the analysis of both narratives and network maps also result from the understanding that structural notions from social network analysis should be used as sensitizing concepts in qualitative network analysis. The procedure they suggest includes numerous questions on structure, actors and relations, with the aim of sequencing the analysis. Writing memos is another essential element of the QSA approach used throughout the process, to reflect upon and maintain the circularity of the analysis.

5.2 The interpretation of network map interviews is presented as a three-step procedure: Step A analyses the map; Step B analyses the corresponding narrative; Step C combines the results of the previous steps. As mentioned above, the idea behind this qualitative analysis is to gain an insight into the subjective meanings and the importance of the ties or relationships to the interviewee. (cf. Flick et al. 2004) To show how this method for qualitative network analysis can help uncover such subjective meanings, each of the three steps of the method will be first introduced and then applied to data from an interview with an international student about her important alters.

6.1 The first step of the analysis consists in writing up an interpretation of the map, independently of the narrative. For this step, Herz et al. (2015) suggest looking at the map in a specific way, in order to structure the analysis in sequences. To do so, they offer questions related to the network structure, originally derived from social network analysis and adapted to qualitative analysis leading to Qualitative Structural Analysis (QSA). The questions described in detail in Herz et al., paragraph 22-27, address the network's density, the embeddedness of actors and the types and properties of ties. This step was done in an interpretation group, which was not informed about the roles the alters had with regard to ego in order not to influence their interpretations. Jointly, the analysts worked on the questions from QSA, moving from a more generic description of the map towards more specific assumptions as described below.

6.2 This step includes looking at the map as a whole and then at specific alters and clusters, taking note of all the alters on the map, their names, roles, adjectives and other kinds of ascriptions. Any places, objects, ideas or activities are also considered as alters, since these entities can be important in the interviewee's everyday life, too. Then the alters' positions are looked into, because the stimulus at the beginning of the interview entails a positioning depending on their importance to ego. The connection between the naming and positioning is also taken into consideration and explores questions such as: what kinds of names (e.g. first names or surnames), what roles (e.g. mother or professor) and what entities (e.g. country or job) are placed close to ego and which are further away from ego?

6.3 At this stage, any groupings, triads, and distant or isolated alters, as well as any oppositions or symmetries are noted in the memo of the map analysis. The interviewee may have highlighted them using arrows, lines or sticky notes of the same colour, but they may also be visible in the analysis without these explicit specifications. Up to this point, the interpretation focuses on understanding who or what the alters on the map are and what they mean to ego. Then, a closer look is taken at the alter-alter relations, the aim being to explore their meaning to ego. The questions posed here touch on the kinds and qualities of relationships there are between the alters, on their influence on the rest of the network and on ego.

6.4 In summary, the analysis of the map, conducted adapting the method for Qualitative Structural Analysis by Herz et al. (2015) aims at collecting assumptions and questions about ego and its network, including the alters' meaning to ego and to the network. The assumptions concern the alters' roles, the meanings of ties, groupings or other formations to ego and their role in the network in general. The following gives an example of this first step of analysis.

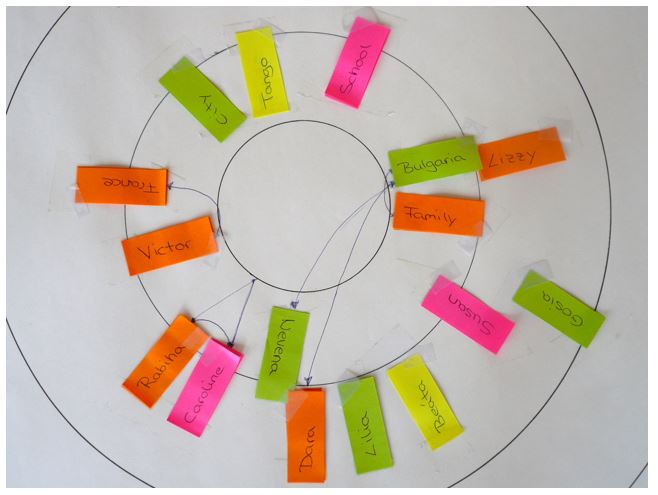

7.1 Following the method presented, the first step of the analysis consists in analysing the egocentric network map produced by the interviewee while narrating. An example of a map will now be analysed in summary. For reasons of tangibility and space, the interpretation will focus mainly on the role of the places mentioned on the map and will closely follow the process by which each assumption develops.

|

| Figure 4. Nevena, network map |

7.2 Nevena's network map is characterised by a number of alters distributed evenly in the first two circles. All the people she mentions are concentrated in the lower half of the network map. (The Nevena on the map is not ego but happens to have the same name. The analysts in the interpretation group did not know the respondent's name so they were not irritated by this.) Further contacts include abstract concepts of activities and places such as school, city and tango as well as two countries. These latter non-people entities are concentrated in the upper half of the map.

7.3 Some of the alter-alter relations are marked with lines and arrows between individual people and also between countries and people. Bulgaria is placed very close to ego and collects three out of the four country-people connections, including a multiple alter: family. This accumulation emphasises the importance of Bulgaria and its cluster. On the opposite side of the ego circle, France is slightly farther away from ego and not connected in any way to Bulgaria, not even indirectly via other contacts. France is connected to one alter, only, which reflects its lesser importance.

7.4 Since it is placed very close to Bulgaria, it seems likely that Nevena's family is situated there, whereas the other alters connected to Bulgaria appear to be further away, presumably in a geographical sense. Assumptions which can be made here are that these latter alters somehow 'belong' to Bulgaria. Perhaps it is their country of origin and they are currently not there, or else Nevena did not first meet them there. This belonging despite geographical distance is expressed by her not placing these alters as close to Bulgaria as her family, but connecting them to each other, nevertheless.

7.5 Along these lines, another hypothesis is that not only do the people belong to the country but also the country can be linked to the people without their actually being there: the fact that all the arrows touch or pass through ego is a phenomenon which requires an explication. All these relationships may concern or influence ego, or in turn be influenced by ego. One possible interpretation is that ego neutralises the distance between the alters, becoming the connector between the people and the country. According to this understanding, Nevena's own effort would then bind them together, not necessarily the alters' own effort. This effort has a direct consequence on the alters' importance: those who are connected to one of the countries are closer to Nevena than those who are not. Her effort and/or their belonging increases their relevance on the map.

7.6 Assumptions derived from looking at the upper part of the map, are that 'city' means one specific city in one of the two countries mentioned in the map, but it could also imply the concept of the city as a place in which Nevena can meet people or pursue hobbies and activities. In this case, the three alters at the top of the map would be independent of place and therefore universal. Or else they are currently not available or geographically far away, which is reflected by their being somewhat segregated from the other alters. A final assumption based on the consideration of these entities is that in Nevena's international context people move often. Connections to people are not stable, since they may leave at any time. Important people may be geographically far away and unable to provide the support needed. Therefore, these universal institutions such as school or tango, and places such as the city, become more relevant, because they can offer continuity and permanence.

7.7 One supposition is that Nevena is bound to two countries and is at the same time trying to establish a relationship to where she currently is – a place which does not become clear from the map. She is therefore maintaining relations with people connected to all the countries in question. At the same time, she shows that a few abstract ideas are very important to her although they are not expressly connected to any of the other alters. These can be seen as her own personal resources or topics, which she does not or cannot share. The map is therefore separated into an upper section with abstract entities, a left-hand section connected to one country, a right-hand section connected to the other country plus two extra contacts, a triad and a collection of individual contacts. This quite specific segmentation can then also be looked into in the narration.

7.8 Summarizing, the following assumptions were made from the map when focussing on the role of places and entities in particular:

8.1 The second step consists in analysing the narrative which has arisen from the interview. In this study, this is done by first selecting specific passages, e.g. the beginning, the end and any passages which contain information about topics related to the research question, which discuss topics mentioned often in the interview or which are stressed by the respondent. These passages are analysed in detail and the rest of the interview is searched through to find other related passages to be analysed. The analysis aims to understand what a topic means to the student's narration and can result in various differing interpretations. Again, the results of this analysis are assumptions and questions about what the relationships described mean to ego and about the roles the various relationships play in the network. This procedure differs slightly from the one suggested by QSA since it first selects passages independently of the analysis of the map. In QSA, the assumptions and questions collected in memos during the map analysis lead directly to a sampling of sections from the narrative which might offer answers to these open questions. Additionally, QSA would also ask questions focussing on structure, actors and ties in the analysis of the interview to introduce a structural perspective. According to the approach suggested here, these steps suggested by QSA, i.e. selecting passages from the narration to answer questions arising from the map analysis, would follow a sequential analysis which first collects assumptions from each set of data.

9.1 The second step, the analysis of the narrative, also leads to a collection of assumptions, based on a comprehensive analysis of passages from the interview. A few example sections and fragments from the narrative will be presented in full or summarised and briefly discussed, before selected assumptions are put forward. The following are passages and particles from the interview with Nevena, the same student who created the network map shown and discussed above. They were selected not only according to their relevance to the research question, but also because they discuss a problem perceived by the student and because they provide subjective meaning-giving and explanations of their situations.

9.2 In the narrative, Nevena describes her life as 'a bit fragmented' and explains this with the feeling she has of not identifying 'a lot with the culture'. This feeling reflects the very first words of her self-presentation: 'I was born in Bulgaria', with which Nevena points out that she is not from here and is also now living an 'international life'. She mentions both her 'fragmented' life and her not identifying with the culture as not absolutely satisfactory circumstances. She explicitly expresses the wish for her life to be whole and to feel more linked to the culture. Identification with the surroundings is important to her, but at the moment she cannot connect to the place she is living in, or to the people either, as she explains further. When talking about her own and other international academics' relationship to the place they are currently living in, Nevena states: 'This is nOt the final destination. It's just a trAnsit […] nobody is connecting with the place or nobody is LETting themselves connect with the place. Maybe that's the problem. Maybe I'm ** I'm not letting myself FEel like home here knowing that, at some point, I will have to LEAVE. It's not just the…the culture that is foreign. It's ME that I'm being foreign in this culture. So, somehow, I think it's a SELF-IMPOSED * EXILE.'

9.3 'So, in a way, our life is not * really * stAble, […] we don't know if this is our final destination. […] sometimes, it provokes a lot of anxiety but at the same ** time, it's=we're frEE. We're free to decide that we want to move if we don't like a place.' What Nevena previously called an 'international life' she now also calls 'not stable'. At first she characterises the state negatively, since it produces anxiety, but the second attribution is quite positive, since the instability also means a life of freedom, at least regarding the place of residence. The price for this freedom is high, but she and her partner are currently willing to pay it.

9.4 Shortly after, she continues talking about her current situation and speculates about the reasons for people's not wanting to connect to the place: 'Maybe that's why people don't want to invest a lot=emotionally because then * they get attached to someone ** and then they go AWAY and you don't know if you'll ever see them again.'

9.5 Nevena is not content with her current situation concerning friendships because she has the feeling she needs to invest too much effort into finding and keeping friends: 'I'm missing having EASIER relationships that don't need so much INput and so much EFFORT […].'

9.6 The difficulty in establishing easy friendships is explained in another passage: 'Well, there is another problem, it's weird because ** like, * here people come and go sometimes **. So, in a way, for example, I'm thinking of my friend who left […]. I could have PUT him in the list, (I: Uh-huh) but six months ago he left.' This specific case of one of her friends shows that the people's coming and going impedes a clear categorization in important and not important. The person she is talking about is a friend and could have been positioned among the important people, nevertheless his departure makes this impossible. It is not the fact that he is currently abroad which complicates the classification, since Nevena has mentioned a few other people who live abroad and are still very important. What leads to his being dropped off the list is the combination of his having once lived there and now being abroad. This goes to show that the fluctuation of the relationships due to the mobility of the people in question makes the status of the relationships unclear and problematic.

9.7 Nevena then talks about a friend of hers who lives in the same city and with whom she enjoys spending time: 'I'll put her here because she's also important […] also because she reminds me of home. She was my brother's ex-girlfriend, so ** somehow probably she's a MENtal connECtion to home, family. **Uhm * when we go and we buy that STUPID thing from the POLISH store that have BULGARIAN labels, we share them and we ENJOY it.' This friendship is based on their sharing something: food but also a specific background. Because they are able to enjoy certain things from certain countries, this friend connects her to home.

9.8 From these passages and from the others interpreted from this interview, various assumptions were made, a few of which are described very succinctly in the following: the international student's "international life", as she calls it, involves a marked mobility, and an insecurity as to where she and where the alters will live in the future. Therefore, a constant instability in her connections and highly differentiated personal communities are to be found in her network. Her current place of residence is denoted by fluctuation and detachment, both on her own part and on others', making it difficult for her to feel at home but at the same time also giving them the feeling of being free to choose where they want to live.

9.9 A few connections have proved to be closer, thus more important: those who are connected to her home country either because the people are still there, or because they come from there and are currently abroad, like herself. These are people with whom she can share memories and connect through the memories and experiences. At the moment it is impossible for her to establish other closer relationships, although she feels she is trying hard to do so, or investing a lot, as she puts it. The difficulty and its consequences can also be visualised in her own words: she feels she is living 'in a bubble'.

10.1 After the analyses of both the map and the narrative, a combination of the two aims to provide a broader picture. This last step combines the results from the two analyses, focussing on how they do and do not converge: where they provide converging, diverging or complementary information about the network in general, about ego, the alters in ego's life, the connections in the network, and their roles and meanings to ego.

10.2 In this study, the combination of the analyses occurs at this final stage, because the two sets of data are of a different type (text – visualisation) and were each analysed using specific methods, as described above. Nevertheless, an earlier combination of the data sets may also be very instructive, e.g. if the assumptions from the map are used to select passages from the narrative for analysis, as also suggested for QSA by Herz et al. (2015).

10.3 This step revolves around these questions: What issues does the map raise, what issues does the narrative raise and which are to be found in both? What can be transferred from one type of data to the other? What is comparable and what is not? Which additional information does one set of data provide compared to the other?

11.1 The following discusses a few of the main topics which arise from the combination and comparison of the analyses above, and highlights aspects which can be found mainly in one of the two sets of data.

12.1 Various relevant alters found both in the map and in the narrative are geographical ones: the interviewee names five countries, eleven cities, various nationalities, a few regions and a continent, showing that places play an important role in her current life. As already mentioned, the connection to a country increases people's importance, as can be seen clearly on the map: those who are connected to her home country are closer to her, or those important to her are connected to one of the two main countries mentioned. In general, places influence other alters in Nevena's current network because they influence their occurrence, vary the frequency of contact between her and them, or even prevent other alters from being of importance, due to their being distant. These topics (places and distance, as well as frequency of contact) can provide a starting point for further analysis, which would then look deeper into the meaning of places in Nevena's life.

13.1 A topic which arises after the analysis of the narrative but which was not found in the map, is Nevena and her husband's feeling of freedom. Their freedom to move and choose the place they want to live in is her positive interpretation of their current situation. Their "international life" is reflected in the map, and the interpretation connected to this mainly concerns the effort which Nevena has to make to keep the scattered alters in her network, not the freedom it entails. The positive connotation of freedom was not brought up when looking at the map. In this case, therefore, the narrative offers additional subjective interpretations of the situation.

14.1 The general segmentation of the network can be observed very well in the map. The interviewee has friends and contacts in various places, countries and contexts. She positions them according to what she has in common with them: their background, their interests, their origin. Only very few of her contacts share anything between each other, which leads to them not being connected among themselves. The few connections which can be made are assumptions based on common colours and on arrows drawn onto the map. According to these, countries or activities then connect people to one another. Still, the ties only exist in relationships to the ego as shown in the map: without Nevena, the relationship would not exist, which shows how fractionated the network is. This was also found in the narrative, in which Nevena states that her life is fragmented. Nevertheless, the precise separation of people, places and entities as well as the connections marked on the map are a much more obvious representation of the fragmentation, since they actually make it strikingly visible on paper. Drawing from this last preliminary combination of the results from both sets of data, further analysis of this theme would then focus on the consequences of the fragmentation on the network, how Nevena rates and contextualises it and what role it plays in her everyday life.

15.1 As in any research project, it is necessary to reflect upon how the method of data collection and the analysis method is used, in order to understand their effects on results. The interviewee's questions and interest will influence the respondent's answers, the network map will inevitably introduce a focus on relationships and the questions used during the process of analysis will entail specific findings. Even though a certain level of standardisation is used (e.g. interview guidelines and semi-structured network maps), in qualitative research as discussed in this article it is also important to be able adapt to the interview situation and focus on issues put forward by the interviewee. In order to e.g. discern which effects may come from which stimuli during this research study it proved helpful to keep the mentioned issues concerning the focus and method in mind while also resorting to interpretation groups, writing memos after the interviews, during the map interpretation sessions and during the analyses of the narration.

15.2 In order to collect a broad analysis of the data, for example, the analyses were conducted in interpretation groups with various researchers. Among others, Przyborski and Wohlrab-Sahr (2008), Küsters (2009) and Kleemann et al. (2013) suggest this procedure in qualitative social research because it offers a chance to exchange and collect diverging interpretations of the data. The interpretation group can then discuss the different interpretations and check their plausibility based on further data, in order to select the one which seems most valid to them. If various interpretations are substantiated, they may also be merged into a more comprehensive one. Apparent inconsistencies in the data and contradicting interpretations pose questions which the group can use for subsequent analysis. By working with various perspectives, this procedure aims to ensure intersubjective replicability.

15.3 Further, when analysing the maps and narratives, it proved fruitful for the study to look into each set of data with a group of people who had not yet dealt with the other set. The interpretation group analysing Interviewee X's map had not read the corresponding narrative. In turn, the interpretation group analysing Interviewee X's narrative had not seen the map completed by X. This offered the researchers the chance to collect fresh interpretations of one set of data freely, without the interpretations of the other set at the back of their mind. Similarly, during the analyses, the interviewer tried not to influence the interpretation too strongly with any additional knowledge she had, but which the others in the interpretation group did not have. Again, this procedure was aimed at leaving the interpreters free to collect interpretations which the interviewer, who knew the data in its entirety, might not have thought about or might have prematurely rejected. In the analysis presented, the researcher therefore refrained from providing any information, details or explanations which could not be found in the data being analysed. This procedure aimed to ensure that different perspectives were collected, so as to provide a broad range of interpretations to draw from. A final strategy used in order to minimise interferences in the analysis of the data was that of analysing the maps at a different time from the narratives. By doing so, researchers who analysed both data sets from one interview (map and analysis), would not transfer assumptions from one set of data to the other.

16.1 In summary, the article shows that focussing equally on the maps and on the narratives, and looking into each of them using specific methods, provides an opportunity to approach the interviewees' subjective constructs in two ways, which can lead to similar or different results which are then to be combined. Both paths can uncover structures and meanings relevant to the interviewee, without allocating structure only to the map and meaning only to the narrative. The maps and the narratives each provide relevant data-based assumptions.

16.2 It is important to stress that this method of qualitative analysis of the maps does not involve their "quantification". Instead, the map is seen as a visualisation of network structure and meanings and is translated into text, not into numbers, during an interpretation session. Although network maps could be regarded as pictures, the method exemplified here focuses on another aspect of the visualisation and is not derived from visual analysis: it is not the picture of the network as such which is described, but rather the network's structure as visible on the map.

16.3 Such a method allows us to also look beyond dyads by asking how alters are linked to the other alters, including things, places, ideas, crises, beliefs, festivities, activities and various other such entities. Including such entities in the study revealed that support was provided to the students by human entities, by non-human ones and also by the relationship between various kinds of alters in particular ways. The role of non-human entities therefore proved to be important in shaping the interviewees' social environment. Since it is not a common practice to include non-human entities in sociograms although they may be of major importance to ego, further reflection on this issue is needed.

16.4 This method can also be used to uncover discrepancies between the meaning of important relationships as seen by the researcher and by the interviewee. It gives the researcher the opportunity to engage with various interpretations by applying two methods of analysis to two sets of data which are distinct but intrinsically entwined. It thereby provides an approach to the qualitative analysis of network map interviews in a manner which does justice to both sets of data and enables their simple and effective combination.

BERNARDI, L (2011) A Mixed-Methods Social Networks Study Design for Research on Transnational Families. Journal of Marriage and Family 73. August 2011, p. 788-803. [DOI:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00845.x] [doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00845.x]

BIDART, C. and Charbonneau, J. (2011): How to Generate Personal Networks: Issues and Tools for a Sociological Perspective. Field Methods 2011 23: p. 266-286. [DOI: 10.1177/1525822X11408513] [doi:10.1177/1525822X11408513]

DIAZ-BONE, R. (2007). Gibt es eine qualitative Netzwerkanalyse? Review Essay: Betina Hollstein & Florian Straus (Hrsg.) (2006). Qualitative Netzwerkanalyse. Konzepte, Methoden, Anwendungen [38 Absätze]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(1), Art. 28, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0701287.

FLICK, U., von Kardoff, E. and Steinke, I. (2004) What is Qualitative Research? An Introduction to the Field in Flick U, von Kardoff E and Steinke I (Eds.) A Companion to Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications, p. 3-11.

HERZ, A. (2012) Erhebung und Analyse ego-zentrierter Netzwerke in Kulin S, Frank K, Fickermann D and Schwippert K (Eds.) Soziale Netzwerkanalyse. Theorie – Praxis – Methoden. Münster: Waxmann, p. 133-150.

HERZ, A. and Olivier, C. (2012) Transnational Social Network Analysis. Transnational Social

Review: A Social Work Journal, 2(1), p. 11-29. [ ]

HERZ, A., Peters, L. & Truschkat, I. (2015). How to do qualitative structural analysis? /The qualitative interpretation of network maps and narrative interviews [52 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(1), Art. 9, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs150190.

HOGAN, B, Carrasco, J.A. and Wellman, B. (2007) Visualizing Personal Networks: Working with Participant-aided Sociograms. Field Methods; 19(2): p. 116-144. [DOI: 10.1177/1525822X06298589] [doi:10.1177/1525822X06298589]

HOLLSTEIN, B. (2011) Qualitative Approaches in Scott J and Carrington P.J. (Eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis, London/New Delhi: Sage. [doi:10.4135/9781446294413.n27]

HOLLSTEIN, B. and Pfeffer, J. (2010). Netzwerkkarten als Instrument zur Erhebung egozentrierter Netzwerke in Soeffner H-G (Ed.) Unsichere Zeiten. Herausforderungen gesellschaftlicher Transformationen. Verhandlungen des 34. Kongresses der Deutschen Gesellschaft f117r Soziologie in Jena 2008. CD-Rom. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, http://www.pfeffer.at/egonet/Hollstein%20Pfeffer.pdf.

KAHN, R L and Antonucci, T. C. (1980) Convoys over the life course: Attachment, roles, and social support in Baltes P B and Brim O G (Eds.) Life-span development and behaviour, New York: Academic Press.

KEIM, S, Klärner, A. and Bernardi, L. (2009): Qualifying Social Influence on Fertility Intentions: Composition, Structure and Meaning of Fertility-relevant Social Networks in Western Germany. Current Sociology, 57(6): p. 888-907. [DOI: 10.1177/0011392109342226] [doi:10.1177/0011392109342226]

KLEEMANN, F., Krähnke, U. and Matuschek, I. (2013): Interpretative Sozialforschung. Eine praxisorientierte Einführung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [doi:10.1007/978-3-531-93448-8]

KÜSTERS, I. (2009) Narrative Interviews: Grundlagen und Anwendungen. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. [doi:10.1007/978-3-531-91440-4]

MCCARTY, C, Molina, J. L., Aguilar, C. & Rota, L. (2007) A Comparison of Social Network Mapping and Personal Network Visualisation. Field Methods, 19(2): p. 145-162. [DOI: 10.1177/1525822X06298592] [doi:10.1177/1525822X06298592]

OLIVIER, C. (2013) Papier trotz Laptop? Zur wechselseitigen Ergänzung von digitalen und haptischen Tools bei der qualitativen sozialen Netzwerkanalyse in Schönhuth M, Gamper M, Kronenwett M and Stark M (Eds.) Visuelle Netzwerkforschung. Qualitative, quantitative und partizipative Zugänge (p.99-119). Bielefeld: transcript.

PETERS, L., Truschkat, I. & Herz, A. (2016). Organisation - Institution - Netzwerk - Zur Analyse organisationaler Einbettung über die Qualitative Strukturale Analyse (QSA). In: Schröer, A., Göhlich, M., Weber, S. M. & Pätzold, H. (Hrsg.). Organisation und Theorie. Beiträge der Kommission Organisationspädagogik. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, S. 273-282.

PRZYBORSKI, A. and Wohlrab-Sahr, M. (2008). Qualitative Sozialforschung: Ein Arbeitsbuch. Munich: Oldenbourg Verlag.

RYAN L, Mulholland, J. and Agoston, A. (2014) Talking Ties: Reflecting on Network Visualisation and Qualitative Interviewing. Sociological Research Online, 19(2): http://www.socresonline.org.uk/19/2/16.html [doi:10.5153/sro.3404]

RYAN, L. and Mulholland, J. (2014) French Connections: The Networking Strategies of French highly skilled migrants in London. Global Networks, 14(2): p. 148-166. [doi:10.1111/glob.12038]

SCHÖNHUTH, M., Gamper, M., Kronenwett, M. & Stark, M. (2013) Visuelle Netzwerkforschung. Qualitative, quantitative und partizipative Zugänge. Bielefeld: transcript.

TRUSCHKAT, I. (2016). Schule im Kontext regionaler Übergangsstrukturen. Zur Reziprozität und Balance in Bildungsnetzwerk. In: Kolleck, N., Kulin, S., Bormann, I., de Haan, G. & Schwippert, K. (Hrsg.). Traditionen, Zukünfte und Wandel in Bildungsnetzwerken. New York: Waxmann, S. 129-144.

TUBARO, P, Casilli, A. and Mounier, L. (2014) Eliciting personal network data in web surveys through participant generated sociograms. Field Methods 26(2): p. 107-125