Solo-Living, Demographic and Family Change: The Need to know more about men

by Lynn Jamieson, Fran Wasoff and Roona Simpson

University of Edinburgh

Sociological Research Online 14(2)5

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/14/2/5.html>

doi:10.5153/sro.1888

Received: 30 Sep 2008 Accepted: 25 Apr 2009 Published: 30 May 2009

Abstract

Solo-living is analytically separate from 'being single' and merits separate study. In most Western countries more men are solo-living than women at ages conventionally associated with co-resident partners and children. Discussions of 'demographic transition' and change in personal life however typically place women in the vanguard, to the relative neglect of men. We draw on European Social Survey data and relevant qualitative research from Europe and North America demonstrating the need for further research.

Keywords: Family Friendship Gender Intimacy Solo-Living One-Person Household

Introduction

1.1 This paper seeks to consolidate and develop understanding of the trend of living alone among the working-age population, locating this within the frame of wider demographic and family research. Our focus is particularly on solo-living among the age group above the median age of co-residence with a partner and below the age of 60. We draw on the European Social Survey (ESS) (Jowell 2003, 2005) and published quantitative and qualitative research including our own secondary data analysis of UK and Scottish nationally representative data sources (Wasoff et al, 2005a, b).1.2 Census data indicate that living alone at ages more conventionally associated with living with a partner and children has increased across a range of 'western' countries in the last three decades and has often increased dramatically. While the ESS is a much smaller data source than census data, samples sizes are sufficiently large to enable preliminary comparison of the proportions of people living alone across Europe while offering richer data on attitudes and characteristics than censuses. The percentage of working-age adults living alone remains below 10% in many European countries but is approaching 20%, at least amongst men, in the parts of Europe leading the trend. If households are examined rather than individuals, the proportion of one-person households among this age group is much higher.

1.3 The trend of increase in solo-living at ages more conventionally associated with being partnered and raising children is relevant to two related fields of study of social change, the debates of demographers over the 'second demographic transition' and among social scientists over the alleged turn to hyper-selfish individualism or heightened self-reflexive individualisation. Solo-living has not been well integrated into discussion of the former, despite its obvious relevance to concerns about low fertility. It has been made an explicit reference point by discussants of the latter, as if solo-living is the end point of processes of individualism and individualisation. Ulrich Beck (Beck, 1992, Beck-Gernsheim, 1995) is the best known presenter of this position: 'Everyone must be independent, free for the demands of the market … the market subject is ultimately the single individual [that is unpartnered and living alone]…. The ultimate market society is a childless society' (Beck & Beck-Gernsheim 1995: 116). While the broad sweep claims of variants of the 'individualisation thesis' have been increasingly critiqued, individualism and individualisation continue to be used by a range of social scientists as if they both capture and explain social change. Moreover, living alone continues to be cited as if exemplifying the nature of contemporary social change. For example, in a recent report on social change in Britain commissioned by the BBC solo living was one measure in indices of 'anomie' and 'loneliness' used to capture social fragmentation (Dorling et al 2008), with its wide use in other academic research cited in justification.

1.4 Beck and Beck-Gernsheim equate solo living with market driven selfish individualism. Acknowledging a much older argument (Berger and Kellner 1964, Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, 1995, 52-53) they claim that more individualised and atomised existences make people more desperate for love and coupledom. At the same time, they suggest heterosexual couples are less likely to sustain successful relationships because capitalist market forces have both equalised the participation of women and men in the labour market and heightened self-interested gender antagonism.

1.5 Zygmunt Bauman (Bauman 2001, 2003, 2005) and Anthony Giddens (Giddens 1990, 1991, 1992) share many of Beck's presumptions but the former is yet more pessimistic and the latter more positive in his analysis of social change. They agree that individuals are more disembedded than ever before from all traditional ties and loyalties such as social class, place, community, and, consequently, more self-consciously self-reflexive, experiencing more and more of life in terms of individual decisions about how things are done. Like Beck, both emphasise the resulting fragility of family and personal life. Bauman emphasises the corrosive effect of the pervasive cultural emphasis on hyper consumption, fluidity, mobility and disposability, which undermines human capacity and endeavour of sustaining durable and meaningful relationships.

1.6 Giddens, in contrast, can perhaps be read as reclaiming the Durkhemian possibility of a socially integrative moral individualism (Santore, 2008). The Transformation of Intimacy (1992), is the most cited version of his optimistic account. Giddens does not assume a move towards 'the single individual' but, like some North American commentators (Stacey 1990, 1996; Skolnick 1991), to more equal and democratic forms of intimate relationships. He suggests that individuals disembedded from tradition, sensitised to the fragile and arbitrary nature of the social world, have not only a heightened sense of risk but also of their own creative ability to construct 'a narrative of the self' (1992, 75). Like Beck, he argues that the absence of certainties creates a search for self-affirmation through intensely intimate personal relationships, but rather than gloom about their fragility, he sees this as an opportunity for new intensity of intimacy constructed through a dialogue of mutual self disclosure which is simultaneously a new democratisation of personal relationships. Rather than seeing women as reduced to the same selfishness of men, women, as the more skilled practitioners of self-disclosing intimacy, along with same-sex couples unhampered by outmoded gender scripts, lead in this positive vision of democratising social change.

1.7 Collectively these types of arguments have been referred to as the individualisation thesis or detraditionalisation thesis. The ideology of individualism, the notion that an individual is a proprietor of his (and not, at the time, her) own person, has a very long history predating capitalism (MacFarlane, 1978, MacPherson 1962). In family research of the 1970s and 1980s there was a flurry of using 'individualism' to try to explain what was then called the development of 'the modern family'. It was then as inadequate an explanation (Jamieson, 1987) as it is now, and was being used as an inappropriate shorthand to cover a complex package of interconnected changes that occurred in the post-war period.

1.8 A number of authors have mounted direct challenges to the more recent uses made of reflexive individualisation by Beck, Bauman and Giddens, itemising ways in which their arguments caricature rather than explain social change in gender relations, noting disregard for several decades of more nuanced and evidenced feminist scholarship and research on family life or variously claiming neglect of how people see and conduct their personal lives (Brannen and Nilson 2005, Charles et al, 2008, Crow 2002, Duncan and Smith 2006, Irwin 2005, Jamieson 1998, 1999, Smart 2007). Beck's and Giddens's conceptualisation of tradition, disembedding, reflexivity and subjectivity have all been subject to challenge (Adkins 2005, Charles et al. 2008, McNay 2000, Gross 2005). Nevertheless, with respect to solo-living, the claims of selfish-individualism and social fragmentation remain in circulation in both academic and popular work.

1.9 Within debates in both domains, among the key sociological authors who have made major claims concerning social change and individualisation and among demographers reflecting on the 'second demographic transition', women are often construed as at the leading edge of social change. Factors stressed by demographers in explaining recent change include women's ability to control their fertility; heightened expectations of equality in a relationship with a partner; the integration of women, including mothers, into the paid labour force; women's attempts to balance paid work and family life, and the greater likelihood that women will initiate legal steps to exit from partnership arrangements. In sociological debate about the impact of individualism on personal life, again women are often seen as in the lead whether by withdrawing their willingness to sacrifice themselves for their family or by seeking more democratic, egalitarian and intensely intimate relationships. However, the balance of men and women who are solo-living across the years of adulthood prior to retirement age does not fit with this view of women as the main pioneers. More men are living alone in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s than women. In this respect solo-living seems to offer a particular conundrum and its more careful study has the potential to bring new insights to these debates. No claim is made to fully unravel this conundrum but the process clarifies the possible gains from further international research focusing on solo-living as distinct from 'being single'.

Analytical distinctions, shifting categories and gender differences

2.1 A focus on people who live alone at ages more conventionally associated with living with a partner and children demands the analytical separation of 'solo-living', 'singles' and 'solos', the categories of residence arrangements, legal marital status and partnership status. Living alone is sometimes called living in a 'one person' or 'single person' household. Unfortunately, the use of 'single person' here is unhelpful and confusing since 'single' is also used to mean both a formal legal marital status and, alternatively, a lack of particular type of relationship. Studies of people who identify themselves as a-couple-who-live-apart (Roseneil 2006, Gierveld 2004, Haskey 2005, Holmes 2006, Levin 2004), remind us not to assume that those who live alone are single in the sense of unpartnered. Many people living alone in the age groups of interest also do not have the legal status 'single' since they have been married at some point. Thus people who live alone may not be single in either the sense of 'unpartnered' or 'never married'. Similarly, as unpartnered people are also to be found in shared living arrangements, such as living in the parental home and sharing households with peers, they are not coterminous with people who live alone. We have adopted the term 'solo-living' which is being increasingly used to refer to people who live alone and insist on the hyphenated combination of terms to avoid confusion with the use some authors make of 'solos' (Marks 1996) to refer to people who are unpartnered rather than the 'solo-livers' that we speak of.2.2 Like 'single' as a category of legal or de facto partnership status, solo-living is not a fixed attribute of the individual but a category that people may move in and out of. The most detailed recent study of such patterns of movement has been in the UK. Linked census data has been used to examine movements in and out of solo-living at ten year intervals (Hall et al. 1999; Hall & Ogden 2003; Chandler et al 2004; Williams 2007; Williams et al. 2004), and the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) to track individuals at annual intervals between 1991 and 2001 (Wasoff and Jamieson 2005a, b). This study of individuals aged 30-74 showed a significantly larger proportion had lived alone at some time in the adult life course than the proportion living alone at any one time. Only 30% of those who had ever lived alone had done so throughout the 11 years. Transitions were much more common for people of working age than above working age. There were also differences in movements in and out of solo-living by gender: transitions were more common for men than women, with 77% of men making at least one such transition compared to 64% of women (Wasoff and Jamieson 2005a, b).

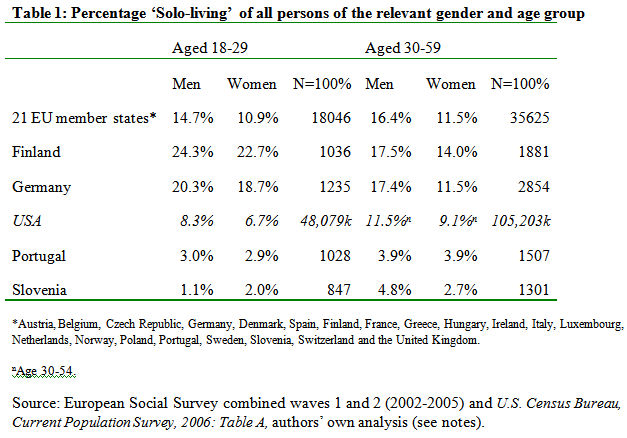

2.3 Below retirement age, men are more likely than women to live solo at any given time. Table 1 shows rates of solo living in selective countries using combined data from the 21 European Union membership countries included in rounds 1 and 2 of the ESS conducted between 2002 and 2005. It also shows the European countries with the highest and lowest levels of solo-living, and comparative figures from US census data. Hungary, Portugal and Slovenia are exceptional in that men and women are either equally unlikely to live alone or have slightly more women living alone than men; in all other countries included in the ESS the proportion of men living alone exceeds that of women.

|

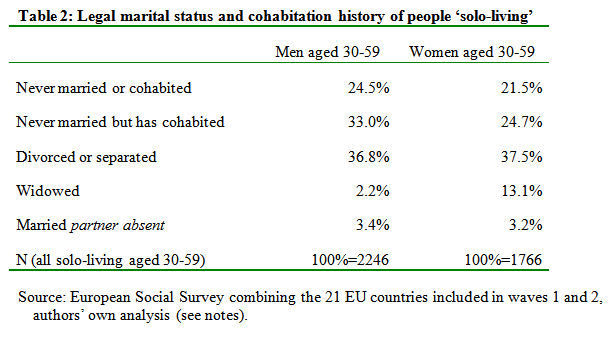

2.4 Table 2 provides an indication of the extent to which solo-living is not in fact coterminous with a legal partnership status of single or of being 'solo' and is suggestive of the diverse routes into solo-living. Those who are solo-living and married will include couples who are 'living apart together' and other circumstances of separation such as having ended the relationship without legal divorce.

|

2.5 The corollary of larger proportions of men of working age solo-living is that larger proportions of women live with a partner or as lone parents with children. In part this is because if a residential union dissolves and there are children, the children overwhelmingly remain with their mothers and men often become solo households. There is however relatively little attention to the experiences, motivations and circumstances of these solo-living men in existing research.

Solo-living and demographic trends

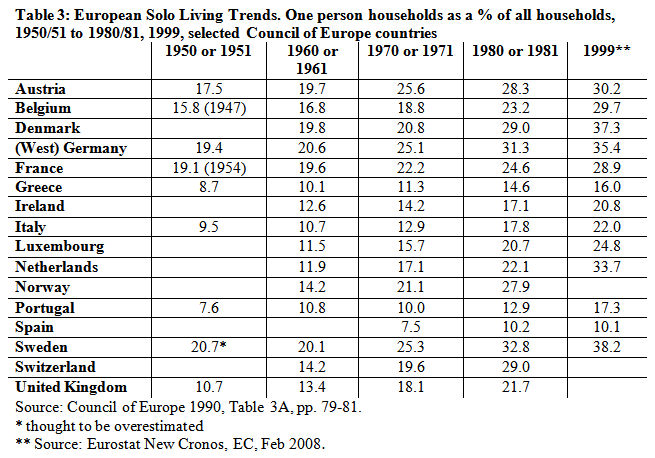

3.1 An interrelated package of demographic changes characteristic of post-industrial 'Western' societies reflect and constitute a transformation of the context in which people may or may not partner and parent. They include new patterns of partnering (later marriage, increased cohabitation and births outside of marriage, higher rates of partnership dissolution); increased childlessness (or a return to previously higher levels); an increase in the average age of bearing a first child and smaller family sizes. Controversy focuses around which are the most significant factors driving change and whether or not it is ever possible to identify primary factors (Caldwell and Schindlmayr 2003; Hobcraft 2004; Frejka 2004; Kohler et al, 2002). Replacement of an idealised 'male breadwinner model' with a dual earner model household and the increasing likelihood of women combining caring for children with employment is generally cited as a key triggering factor, with technologies of reproduction enabling women to control their fertility a necessary condition. Second wave feminism, shifts in balances of power between men and women and demise in conventional notions of appropriate gender roles are also generally recognised as underlying factors. As noted above, these explanations all put particular weight on changes in women's lives and consequently women's decision making.3.2 Discussion of the increase in solo-living is obviously not independent of the trends of deferred and interrupted partnership and later and lower fertility (Kaufmann, 1994). As Table 3 shows, there has been a steadily increasing trend in solo living across a wide range of European countries over the last 50 years, irrespective of the individual rates being low or high.

|

3.3 If it is the case that solo-living has the same roots as these other broad demographic shifts and if women are in the vanguard, it might have been anticipated that women would outnumber men as solo-livers. However, not only are women not in the majority, the demographic context of why they are not includes the persistence of some traditional elements of partnering and parenting and differences in the hazards of negotiating family life for men and women.

3.4 Despite many changes altering the context of 'Western' couple relationships between men and women, the average age of first co-resident partnership remains younger for women than men across a wide range of countries. Women typically partner men who are older than themselves and therefore have children with men older than themselves. This may leave women a shorter period of possibility of solo-living prior to partnerships. The persistence of unequal divisions of labour in bringing up children also leave women with less likelihood than men of solo-living after relationship breakdown if there are children. When partnerships involving children end through divorce or separation, if re-partnership does not directly follow, women are typically left living with children in lone parent families, and men are left living alone (if they don't return to their natal families). Unfortunately the ESS does not ask respondents whether they had ever had a child, but marital status and previous living arrangements are investigated. While Table 2 does not suggest men are more likely to enter solo-living than women following the breakdown of a legal marriage, it shows a larger proportion of solo-living men have formerly cohabited without marriage, a third compared with a quarter of solo-living women.

3.5 Table 2 also shows one way that women were markedly more likely to enter solo-living than men: the proportion of widows is higher among solo-living women aged 30-59 (13%) than among solo-living men of this age (2%). Women are more likely to be widowed than men because men are typically older than their partners and because of higher rates of mortality among men.

3.6 These differences are a descriptive context that raise questions about why more men are solo-living than women. They begin to be suggestive of the possibility that opportunities for choosing solo-living rather than being left solo-living or a single parent may be more open to men than women. It can be anticipated that persistent inequalities in income between men and women affecting their abilities to establish independent households are another factor. Across all of these parts of Europe, women have less earning power on average than men and in this sense they have less opportunity to set up households as solo-livers.

3.7 There is considerable debate among demographers concerning explanations for the variation between countries with low and very low fertility, and between Europe and the USA. It is generally agreed that low fertility is the result of delayed partnership and parenting rather than a desire for fewer children. Therborn (2004) describes four contemporary 'western' variants in the pattern of change in the 'social sexual order' of coupling that have occurred since 1960. Solo-living is not named as such, but 'youth independence', leaving the parental home to live independently, is identified as a significant aspect of some patterns of change. The USA exemplifies one pattern, characterised by contradictory trends which he labels 'the dualism of marriage and non-marriage': higher rates of young marriage, virginal marriage and young childbearing than Europe but also high rates of youth independence, single parenthood and divorce. Northern and western European offers a second pattern combining early youth independence with late marriage. Cohabitation and sex before marriage is a more established norm than in the USA. In contrast, the third pattern of southern European is for young people to live with their parents until they marry, marriage is late and divorce rates and rates of lone parenthood are low. The fourth pattern is of transition in Eastern Europe and the degree of permanent divergence from long established early nearly universal marriage is not yet clear. Divorce rates are high but as yet there is still more marriage, less cohabitation and less early sexual activity than in the northern and western European pattern.

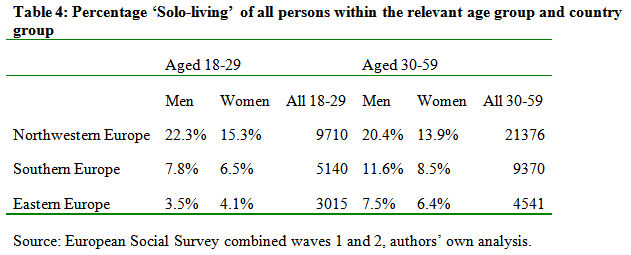

3.8 In Table 4 the countries of the ESS are grouped according to Therborn's categorisation into northwestern (Sweden, Norway, Finland, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, France, UK, Austria, Germany), southern (Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece) and eastern European (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia) groups.

|

3.9 While solo-living is increasing among working age adults in parts of southern and eastern Europe, it is of far greater significance in northwestern Europe. The preponderance of men solo-living is also most marked in northwestern Europe. Rates in the USA (Table 1) are closer to the pattern of southern than northwestern Europe. In northwestern Europe trends fuelling solo-living are combined - growth in delayed or deferred partnering and high rates of partnership breakdown; only the former is shared with southern Europe and the latter with eastern Europe. In addition to the increase in periods outside of partnership, there is also the increased separation of partnering from co-residence (the trend labelled as 'living apart together'), but this should affect men and women equally and is unlikely to match the significance of deferred partnership and partnership breakdown. In northwestern Europe trends in partnership formation seem to be combined with other conditions that make establishing a solo-living household more beckoning to men than women.

3.10 Despite some common structural changes such as lengthening education and delaying access to stable employment arguably extending the transition to adulthood for young people across the 'western' countries, there are also significant cultural variations between the USA, northwestern Europe and elsewhere in Europe in conventional routes out of the parental home. These in turn interact with the availability of affordable housing for young adults and local possibilities available to young men and women for sustaining an independent income (Bendit et al. 1999; Heath and Miret, 1996; Iacovou and Berthoud, 2001). As Therborn noted, leaving home remains strongly associated with marriage in the southern European countries and it is not at all unusual for young adults to remain at home well into their late twenties and early thirties (Heath and Miret, 1996; Iacovou and Berthoud, 2001; Kaufmann, 1994), while in northwestern Europe it is not unusual for young adults to spend a period living independently without co-residing with a partner, a pattern that has also recently developed in the USA (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). Some types of living arrangements, for example student residences, multiple occupancy households, and bed-sit solo-living, act as transitional arrangements between the parental household and a more settled partnered or, for some, more settled solo household (Heath, 2004). The high incidence of partnership dissolution across the adult life course means that the territory of transitional housing, including various forms of solo-renting, is no longer reserved for the life-cycle stage of 'youth'. Returning to the parental home is likely to be less attractive as a possible long term solution when partnership breaks down if it is normative for young adults to live independently of parents prior to partnership.

3.11 Kaufmann's 1994 review of European evidence of solo-living noted that it was most common among men who were either poor or rich. Geographers studying the regeneration of city centres have focused on solo-living as an urban phenomenon with particular concentrations of young professionals (Hall et al., 1999). British data indicate that working-age solo-livers continue to include people living on state benefits in poor quality housing as well as occupants of smart expensive city centre apartments, while solo-living is also not exclusively an urban phenomenon (Chandler et al 2004, Glanville et al 2005, Wasoff and Jamieson, 2005a, b). At the same time, British rural housing studies confirm there are more opportunities for men to be solo-living than women, by demonstrating that childless unpartnered women are the most disadvantaged in rural housing markets (Jones, 2001).

Solo-living, and claims about flights from partnership?

4.1 If the predominance of working-age men in solo-living households has not been seen as a puzzle by demographers, it should have been for participants in sociological debate about the causes of social change in personal life that put women in the vanguard. At one extreme there are claims that excessive individualism, fuelled by labour market conditions and a cultural emphasis on consumption, results in women abandoning their traditional altruism and being as ready to turn their backs on family and long term committed relationships as men. Giddens's counterclaims that as personal life became more fluid, women lead in taking the opportunity to create more democratic and intensely intimate relationships is at the other extreme. In the North American context, empirical research suggesting that men, albeit only some and not all men, and not women have led a 'flight from commitment' (Ehrenreich, 1983; Gerson, 1993) sits alongside continued claims about the corrosive effect of individualism on women's commitments to family (Bellah et al., 1985) . Hochschild's (1989) phrase 'stalled revolution' sums up a widely held view that a main cause of disillusion with family life for women is that men have not travelled far enough to meet women's moves towards equality. But Hochschild also wrote about 'cultural cooling' and women turning away from the 'culture of our mothers' to that of our fathers (2003). Nonetheless, on both sides of the Atlantic, research evidence has shown the continued appeal of marriage or marriage like long-term relationships for both men and women (Cherlin, 2004; Lewis, 2001, Jamieson 1998).4.2 There is as yet little published British work on the personal and familial relationships of men that directly addresses issues of relevance to solo living, despite the fact that the sociology of masculinity and men's studies has incorporated the study of men's personal lives. Men's continued engagements with hegemonic masculinity (Connell 2005, Connell and Messerschmidt 2005) is a strong strand of the sociology of masculinity and men's studies, complementing wider concerns with gender equality in heterosexual partnerships in the feminist literature. These wider literatures addressing men's orientations to heterosexual relationships in Britain do not clearly indicate men in a new flight from committed personal relationships so much as a continuation of difficulties in negotiating equal and emotionally intense relationships associated with hegemonic masculinities. Interview studies of young men's sexuality continues to show that for many men their first sexual relationships with women involve preoccupation with affirmation of masculinity and an imagined audience of other men (Holland et al 1998, Wight 1994) albeit this is an orientation that often changes across a life course as a romantic relationship becomes established (Holland et al 1998, Wight 1996).

4.3 The significant literature on fatherhood in Britain (Clarke and O'Brien 2002, Dermott 2008, Haywood and Mac an Ghaill, 2003, O'Brien and Shemilt 2003, Warin et al 1999) demonstrates wide variation in practices and that the ideal of an emotionally engaged hands-on father is widespread as well as that of father as provider. Fathers are represented among men who are solo living as so-called 'absent fathers', fathers who do not live with their children most of the time, although they may be very involved with them. The literature on 'absent fathers' again demonstrates enormous variation from those who reorient their lives to deepen their relationships with their children in response to the loss of a coresident relationship to those who lose all contact (Bradshaw et al, 1999, Trinder et al 2002). Estimates of the extent of the latter vary but no evidence suggests that it has been increasing over time. The orientation of young childless men to becoming a father is less studied in Britain (O'Brien and Jones 1995) than in the USA (Kaufman and Goldscheider 2007,Marsiglio et al, 2001) but the existing evidence does not suggests men turning away from fatherhood or life long relationships as aspects of their ideal future.

4.4 Although new research is now ongoing, investigation of the motivations and practices of people living on their own at ages normally associated with co-resident partnership and parenting has concentrated on unpartnered women living alone. This reflects, in part, the assumption that women are at the vanguard of change, leading to investigation of whether women were choosing and celebrating living outside of a partnership with men rather than in unequal relationships.

4.5 However, rather than showing women as fleeing from such partnerships, this research offers some insights into why solo-living might be less attractive to women than men. Studies in Europe and North America from the 1990s to the present show that the majority of solo-living unpartnered women have not actively chosen this path and typically begin solo-living with a sense that being coupled is the normal and most desirable state. The experience of continued marginalisation in couple and family oriented societies was a key theme emerging from the early research of Gordon (1994). Sharp and Ganong's (2007) recent U.S. study of unmarried white college educated women aged 28-34 speaks of their sense of a 'missed transition', reflecting earlier British work characterising unpartnered women as in the shadow of marriage (Chandler, 1991). This study, along with Trimberger's (2005) research with ethnically diverse middle-class women, confirms that women in the USA who remain unpartnered have not typically chosen this path. Sharp's and Ganong's respondents were not reconciled to being single but living in a state of uncertainty about the future in which they hedged their bets by both searching for a partner and seeking to secure their quality of life without one. Moreover, studies of younger women and men find women apparently less committed to a period outside of partnerships than men. A British study of single young people in their twenties found both men and women citing advantages of living outside of partnership arrangements for the moment, but while women said they were 'not looking' for a partner they also admitted more openness to the possibility. Young men were much more likely to associate and celebrate a life-style of sexual freedom and freedom to roam with solo-living than were young women (Jamieson et al, 2002).

4.6 This literature begins to suggest that solo-living may be less attractive to women because of the common, albeit sometimes mistaken, assumption that it means settling for being unpartnered. Socially managing the absence of a partner remains more difficult for women than men and the concept of an unpartnered woman continues to have a negative resonance in most western cultures. In Britain, Reynolds and Wetherell (2003, 2007) used focus groups to explore understandings of 'single' for women, concluding it is a 'troubled category'. Although participants did produce positive accounts of singleness as independence, choice, self-actualisation and achievement, they were always aware of negative accounts as personal deficit and experiences of social exclusion. Moreover, the positive versions of being single make it difficult to acknowledge any desire to be partnered, as this runs the risk of being constructed as deficient and desperate. This theme is echoed in other small scale studies (MacVarish 2006; Simpson 2005, 2006). Thus, while in some cultural and socio-economic contexts taking on a mortgage for a home may be seen as a rational part of gathering resources in preparation for partnership by both men and women, the establishment of an independent and non-transitional home may nevertheless be more difficult for women not only because of their lower incomes but because it can be read as acceptance of remaining unpartnered.

4.7 While unpartnered solo-living women do not typically depict themselves as intentionally unpartnered, research also demonstrates that the longer women remain solo-living and solo the less in the shadow of partnership they become. Simpson's research study of unpartnered women found participants living alone depicting this positively, despite several recalling initial trepidation. A majority expressed a preference for living alone and no intention of changing their living status, and, for several, this was portrayed as a source of real pleasure (2005: 228). In one of the few longitudinal qualitative research studies, Trimberger (2005) found that, nine years after an initial interview, women were now much more positive about their lives and had ceased to search for a partner. There are no equivalent longitudinal studies on men's experiences of being unpartnered and living alone.

4.8 Some recent British research that looks at unpartnered men and women does suggest that some groups in the population are moving away from the hegemony of being coupled as the ideal state of adulthood. Roseneil and Budgeon have argued that, rather than being in the shadow of couple relationships, many of their research participants produced accounts of themselves and their lives that successfully de-centred sexual partners (Budgeon 2006, Roseneil and Budgeon 2004,Roseneil 2006). This fits with researchers who suggest the growing importance of adult friendships (Pahl and Spencer 2004, Spencer and Pahl 2006) and a shift in the focus of personal life from the gendered, heterosexual, co-resident, family-founding couple, to a more fluid network of intimates including friends, lovers and neighbours. This view contrasts sharply with the tenor of early research on solo-living women which concluded that many thought that loving intimacy was easier in the context of monogamous partnership, marriages and families (Gordon 1994: 107). However more research is required before generalising from recent small studies of often relatively privileged groups.

Does solo-living make people different?

5.1 If women are often wary of solo-living and largely accidental solo-livers, they are unlikely to consider themselves as very different from women who live with partners. However, the research suggests that as women come to increasingly value their solo-living status, it may become incorporated into their sense of identity. Is solo-living likely to become an aspect of identity for men? For example, are there some who see themselves in permanent pursuit of the sexual freedom and the freedom to roam, that some young British men talked to researchers of (Jamieson et al, 2002)?5.2 It may be theoretically productive to consider what the consequences are for men and women of solo-living as a distinctive site of social construction, for example as a site from which to construct intimate relationships. Different strategies for maintaining intimate relationships are required of those living alone than of those living with others. Because domestic space is not shared, it cannot automatically produce occasions for face-to-face intimacy. If such interactions, intimate or not, are to be an everyday business, they must occur outside the household unless everyday arrangements involve people crossing its threshold. Home can only stage such interactions when others come in. It is immediately obvious that there may be very different possibilities for men and women of feeling safe and remaining respectable while inviting others into their home. The extent of differences will be more stark in some countries and communities.

5.3 As the previous section makes clear, there are very limited data with which to address such questions comparing men and women, since very little qualitative research has focused on men. Survey data do not readily lend themselves to explorations of motivations and subjectivities but rather to comparing the characteristics and behaviours of solo-living men and women with those of men and women living with others, asking the simpler question 'Are they different?' The answer to this question nevertheless might be another step towards deeper insights.

5.4 The use of survey data for cross-sectional comparisons of the socio-economic characteristics of working-age solo-livers and their peers in Britain has confirmed that both groups are heterogeneous (Hall et al 1999; Chandler et al 2004, Glanville et al 2005, Wasoff and Jamieson, 2005a, b). Such comparisons show that while some presumed patterns of differences between solo-livers and others may not exist, nonetheless there are some differences. In the British context, Wasoff and Jamieson (2005a, b) note slightly more polarisation into advantaged and disadvantaged circumstances among solo-living men and women of working age than among those living with others. In particular, a larger minority proportion of solo-livers have disadvantaged circumstances. For example, comparison of housing circumstances shows that access to home ownership is lower and use of social housing higher among working-age solo-livers. Rates of economic inactivity are also higher than among those living with others. Analysis of the ESS similarly indicates the proportion having experienced at least three months of unemployment is higher among working-age solo-livers than among their peers living with others. The gap is larger for men than women, and consistent across Therborn's categories of European countries. In the UK, differences in periods of economic inactivity include a significantly larger proportion of solo-livers who are permanently sick or disabled (Wasoff and Jamieson, 2005a, b). In the ESS, subjective measures of health show slightly higher reporting of bad health by solo-livers but the difference is not large. These data suggest the possibility of a larger sub-group of disadvantaged men and women among solo-livers than among those living with others.

Solo-living and social networks

5.5 Some of the claims and counter claims concerning solo-living have presumed a distinction between the social capital or social networks of those living alone in comparison to those living in more conventional familial arrangements. Again this has been the subject of study in various countries. In an early detailed study of the social networks of solo-living households, Bien and colleagues, based on data from a 1988 representative random sample of the adult population of the Federal Republic of Germany, found that people aged 18-55 living alone were not more socially isolated than those living with others, with social networks 'nearly similar in size, density and frequency of contact to their counterpart' (1992: 172). One difference the authors noted was in the balance between friends and family in the social network of solo-livers with the former predominating to a greater extent, although family were not absent. This is consistent with friends forming a more developed support system for solo-livers than for those who live with partners. More recent British data echoes these findings (Glanville et al 2005, Wasoff and Jamieson 2005a, b). Wasoff and Jamieson also examined gender differences both within the solo-living group and those living with others in patterns of contact with friends, relatives and neighbours. They found greater differences between men and women than between those living solo and with others. Solo women aged 30-59 report consistently higher levels of social involvement with family and community than men in the same age category. Research on kin relationships in northwestern Europe and North America has frequently described women as taking on more of a role of 'kin keepers' than men. Their work suggests that this difference persists among men and women living on their own.

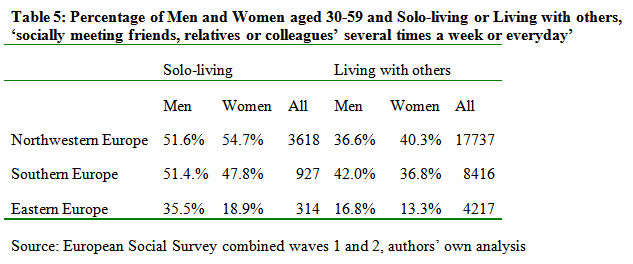

5.6 In the ESS categories of relationship were not separated, rather people were asked 'How often you socially meet with friends, relatives or colleagues'. Across all three regions, a higher proportion of solo-livers answered several times a week or weekly than those living with others. However, the directions of gender differences were not consistent across the three regions. In northwesten Europe women were more likely to meet others socially than men, whether they lived alone or not, but the opposite was true in southern and eastern Europe, indicating that working-age solo-living for women is associated with less sociability in countries where it remains exceptional.

|

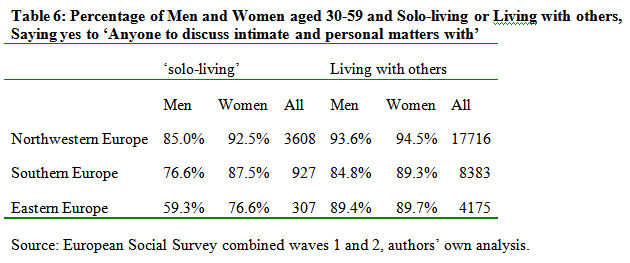

5.7 Sociability and support are not the same thing, and it cannot be assumed that the higher levels of sociability among solo-livers reflect the creation of a wider support network by solo-livers than by their peers who live with others. There are two questions in the ESS survey which measure the availability of support. The first, shown in Table 6, asked people if they had 'anyone to discuss intimate and personal matters with'. This shows a rather different picture. The majority in all categories answer yes to this question. In northwestern and southern Europe, there is a small but consistent difference between men and women and between solo-livers and those living with others, such that women living with others are the most likely and men solo-livers the least likely to have such support . Solo-living men, despite being shown in Table 5 to be more sociable than their male peers, are less likely than their male peers to have anyone they can discuss intimate and personal matters in all three country groupings. However, the difference between men on their own and men living with others is only large in eastern Europe.

|

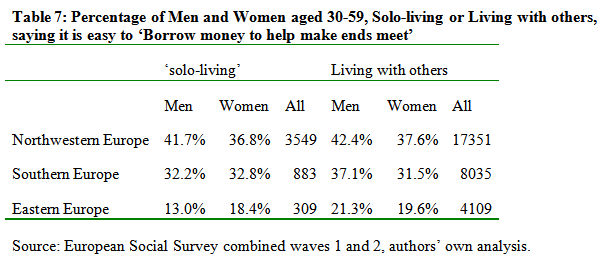

5.8 Finally the ESS also asked about the ease of borrowing money, something that is much more difficult in eastern Europe than in the more affluent northwestern Europe. Here there are no big differences between solo-livers and those living with others, except again for solo-living men in eastern Europe, who are the least likely to find it easy to borrow money.

|

5.9 Like country specific studies, these data confirm that in northwestern Europe, the part of Europe with high rates of solo-living, solo-living men and women are not typically socially isolated or very different from their peers in terms of their access to social support. Indeed differences are greater across parts of Europe than they are between solo-livers and those living with others or between men and women in any one part. One gender difference is cross cutting: it is everywhere less common for men who live alone to claim somebody with whom they can discuss intimate and personal matters, although everywhere the majority are able to do so and differences are typically small. This lack of marked distinction between those living alone and those living with others in northwestern Europe is consistent with movement in and out of solo-living and the limited separation between those who live alone and those who do not. Obviously, the ESS does not in itself offer a full picture. The more marked differences between men and women in eastern Europe than elsewhere remain unexplained. Furthermore, as the data do not address the impact of solo-living on men's and women's sense of self, the relationship between subjectivities and solo-living remains unexplored.

Conclusions

6.1 In making the case that solo-living is analytically separate from 'being single' and that solo-living at ages conventionally associated with co-residence with a partner and parents should be the focus of further study we do not wish to exaggerate the social category nor suggest a new social problem. In combination, the various sources of research drawn on above demonstrate that people who live on their own are neither a homogenous group nor a discrete population that is obviously distinct in characteristics or practices from those who live with others. Rather, we are appealing for further international research which starts with but then unpicks the category through comparatively focusing on difference between genders, socio-economic contexts and cultural circumstances, including those of regions and nations. We advocate in-depth qualitative work exploring the significance of solo-living for men's and women's sense of self, including a focus on solo-living as a distinct site for practices of intimacy and friendship, as well as exploring the bigger picture with snapshots of households generated by surveys and of flows in and out of solo-living through longitudinal data.6.2 Essentially, the reasons for more focused comparative study of working-age solo-living are that it is a growing and widespread trend that is not yet fully understood and often misrepresented. The implication that solo-living is the outcome of shared motivations by a homogenous group of solo-livers is one such misrepresentation. The most striking misrepresentation is the way in which assumptions about the trend gloss over the fact that more men live on their own than women. This is particularly inconvenient for those who wish to continue to recycle widely critiqued versions of the 'individualisation thesis' as accounts of transformations in personal life that place women in the vanguard.

6.3 Variations in solo-living by country reflect variations in the timing and fragility of partnering in combination with the cultural conventions, opportunities and practices which shape patterns of leaving the parental home. However, it seems that the relative consistency across countries of working-age men being more likely to live alone than women can in part be explained by widespread and persistent gender differences that resonate more with traditional behaviour and gender inequalities than women's ability to drive social change: more young women than young men live in heterosexual partnerships; women typically earn less than their male peers and are therefore less economically able to establish independent households; heterosexual partnerships typically involve an age gap with women as the junior partner; when relationships break down women are left looking after any children.

6.4 While socio-demographic data suggest that working-age women's lower rates of solo-living partly reflect lesser opportunities, small scale qualitative studies also suggest an absence of inclination. These studies speak of solo-living women who had not sought to disassociate themselves from being partnered or raising children and who retain some sense of a stigma attached to being a woman on her own. At the same time, they demonstrate that living alone can be a pleasurable and transformative experience for some women encouraging commitment to living alone but not withdrawal from a wider social life. However, this picture and the possible futures that it suggests is not informed by much understanding of the motivations, intentions and identities of men living alone despite the fact that they are the main constituent of working-age solo-living. Living alone is a very particular site for the social construction of a domestic life and a home from which to orchestrate sociability and intimacy with others. It cannot simply be assumed that the consequences for men living alone in terms of their sense of self or forms of engagement with the wider social world will be broadly similar to that of solo-living women who are equivalently rich or poor or from the same cultural and national context.

Notes

1. Regional and Population weights are applied on all tables derived from ESS that combine countries and regional weights alone are applied for comparison between individual countries.2. In all ESS tables, age bands are derived from years of birth as follows: recode yrbrn (1893 thru 1944 =1) (1945 thru 1971 =2) (1972 thru 1992 =3) into agebands.

3. Table 2 The first rows are derived from additional analysis showing that among never married solo-living men, 42.6% have lived with a partner without marriage and among never married solo-living women 46.6% have lived with a partner without marriage.

References

ADKINS, L. (2005).'Reflexivity: Freedom or habit of gender?' in Adkins, L and Skeggs, B. Feminism After Bourdieu Blackwell, Oxford.BAUMAN, Z. (2005). Liquid Life. Cambridge: Polity.

BAUMAN, Z. (2003). Liquid Love: On the Frailty of Human Bonds. Cambridge: Polity.

BAUMAN, Z. (2001). The Individualized Society Cambridge: Polity.

BECK, U. (1992) Risk Society: Towards A New Modernity, London: Sage.

BECK, U. & BECK-GERNSHEIM, E. (1995). The Normal Chaos Of Love. Oxford: Polity Press.

BELLAH, R.N., MADSEN, R., SULLIVAN, W.M., SWIDLER, A.,TIPTON, S.M, (1985) Habits of the Heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

BERGER, P. and KELLNER, H. (1964). 'Marriage and the construction of reality: an exercise in the microsociology of knowledge'. Diogenes 12: 1-24. [doi:10.1177/039219216401204601]

BIEN, W., MARBACH, J. & TEMPLETON, R. (1992) 'Social Networks of Single-Person Households', in Marsh, C. and Arber, S. (eds.) Families and Households: divisions and change. London: Macmillan.

BENDIT, R.; GAISER, W. & MARBACH, J. (1999).Youth and Housing in Germany and the European Union. Opladen: Leske+Budrich.

BUDGEON, S. (2006). Friendship and Formations of Sociality in Late Modernity: the Challenge of 'Post Traditional Intimacy'. Sociological Research Online, 11 /3. [doi:10.5153/sro.1248]

BRANNEN, J. and NILSEN, A. (2005) 'Individualisation, choice and structure: A discussion of current trends in sociological analysis'. Sociological Review 53: 412-428. [doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00559.x]

BRADSHAW, J., STIMSON, C., SKINNER, C. and WILLIAMS, J. (1999) Absent Fathers? London: Routledge. [doi:10.4324/9780203252376]

CALDWELL, J. & SHINDLMAYR, T. (2003). Explanations of fertility crisis in modern societies: A search for commonalities Population Studies 57, pp. 241-263. [doi:10.1080/0032472032000137790]

CHANDLER, J., WILLIAMS, M., MACONACHIE, M., COLLETT. T. & DODGEON, B. (2004). Living alone: its place in household formation and change. Sociological Research Online, 9:3. [doi:10.5153/sro.971]

CHANDLER, J. (1991). Women Without Husbands: An Exploration Of The Margins Of Marriage. London: Macmillan.

CHARLES, N., DAVIES,, C.A. and HARRIS, C. 2008. Families in Transition: Social Change, Family Formation and Kin Relationships. Bristol: Policy Press.

CHERLIN, A. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family 66, pp. 848-861. [doi:10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00058.x]

CLARKE, L. AND O'BRIEN, M. (2002) 'Father involvement in Britain: the research and policy evidence' in Day, R.D. and Lamb, M. (eds.) Reconceptualising and Measuring Fatherhood New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

CONNELL, R.W. (1995) Masculinities Cambridge: Polity Pres.

CONNELL, R.W. and MESSERCHMIDT, J.W. (2005) 'Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept'. Gender and Society 19: 829-859. [doi:10.1177/0891243205278639]

CROW, G. (2002) 'Families, moralities, rationalities and social change ' in Carling, A., Duncan, S. and Edwards, R. (eds.) Analysing Families. London: Routledge.

DERMOTT, E. (2008) Intimate Fatherhood: A sociological analysis. Abingdon: Routledge.

DORLING D., VICKERS, D. THOMAS, B., PRITCHARD, J. and BALLAS, D. (2008) Changing UK: The Way We Live Now. http://www.sasi.group.shef.ac.uk/research/changingUK.html consulted 15th December 2008.

DUNCAN, S. and SMITH, D. (2006) 'Individualisation versus the geography of 'new' families'. Twenty-First Century Society 1: 167 - 189. [doi:10.1080/17450140600906955]

EHRENREICH, B (1983). The Hearts of Men: American dreams and the flight from commitment. NY Anchor Press/Doubleday.

FREJKA, T. (2004) 'The "curiously high" fertility of the USA' Population Studies 59, pp. 89-92.

GERSON, K. (1993). No Man's Land: Men's Changing Commitments to Family and Work. New York: Basic Books.

GIDDENS, A. (1992). The Transformation of Intimacy Cambridge: Polity Press.

GIDDENS, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

GIDDENS, A. (1990). The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

GIERVELD, J. (2004). Remarriage, Unmarried Cohabitation, Living Apart Together: Partner Relationships Following Bereavement or Divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family 66, pp. 236-243.

GLANVILLE, K. MACONACHIE, M., SUTTON, C. AND CHANDLER, J. (2005) Solo Living in Devon: Project Report. Plymouth: School of Sociology, Politics and Law, University of Plymouth.

GORDON, T. (1994). Single Women: On The Margins? Basingstoke: Macmillan.

GOLDSCHEIDER, F. & GOLDSCHEIDER, C. (1999). The Changing Transition to Adulthood: Leaving and Returning Home. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

GROSS, N. (2005) 'The Detraditionalization of Intimacy Reconsidered '. Social Theory 23: 286-311 [doi:10.1111/j.0735-2751.2005.00255.x]

HALL R, OGDEN P E., HILL C. (1999). Living alone: evidence from England and Wales and France for the last two decades. In S McRae (Ed.) Changing Britain. Families and Households in the 1990s. pp. 265-296 Oxford: Oxford University Press.

HALL R, OGDEN P E (2003). The rise of living alone in Inner London: trends among the population of working age. Environment and Planning A 35, pp. 871-888. [doi:10.1068/a3549]

HASKEY, J (2005). Living arrangements in contemporary Britain: having a partner who usually lives elsewhere; Living-apart-together, LAT. Population Trends 122, pp. 35-46.

HAYWOOD, C., MAC AN GHAILL, M. (2003). Men and Masculinities. Buckingham: Open University Press.

HEATH, S. & CLEAVER, E. (2003).Young, Free and Single: Twenty-somethings and Household Change. London: Macmillan.

HEATH, S. & MIRET, P. (1996). Living in and out of the parental home in Spain and Great Britain: a comparative approach. Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure Working Paper Series, 2.

HEATH, S (2004). Shared households, quasi-communes and neo-tribes. Current Sociology, 52, 2, pp. 161-179. [doi:10.1177/0011392104041799]

HOBCRAFT, J. (2004) 'Method, theory and substance in understanding choices about becoming a parent: Progress or regress?' Population Studies 58, pp. 81-84

HOCHSCHILD, A. (2003). The Commercialization of Intimate Life Berkeley: University of California Press.

HOCHSCHILD, A. (1989). The Second Shift: Working Parents and the Revolution at Home. New York: Viking Adult.

HOLLAND, J., RAMAZANOGLU, C., SHARPE, S. and THOMSON, R. 1998. The Male in the Head: Young people, heterosexuality and power London: The Tufnell Press.

HOLMES, M. (2006).'Love Lives at a Distance: Distance Relationships over the Lifecourse', Sociological Research Online 11

IACOVOU, M. AND BERTHOUD, R. (2001). Young people's lives: A Map of Europe. Colchester: Institute for Social and Economic Research.

IRWIN, S. (2005). Reshaping Social Life London: Routledge.

JAMIESON, L. (1999) 'Intimacy Transformed? A Critical Look At The 'Pure Relationship', Sociology 33:477-494

JAMIESON, L. (1998). Intimacy: Personal relationships in modern societies Polity Press, Cambridge.

JAMIESON, L. (1987). 'Theories of family development and the experience of being brought up' Sociology 21: 591-607. [doi:10.1177/0038038587021004007]

JAMIESON, L, STEWART, R., LI, Y., ANDERSON, M., BECHHOFER F. AND MCCRONE, D. (2002). Single, 20 something and seeking? in Allan, G & Jones, G. (eds.) Social Relations and the Life Course Palgrave, London pp. 135-154.

JONES, G. (1991). Fitting Homes? Young People's Housing and Housing Strategies in Rural Scotland, Journal of Youth Studies, 4, pp. 41-62 [doi:10.1080/13676260120028547]

JOWELL, R AND THE CENTRAL CO-ORDINATING TEAM (2003). European Social Survey 2002/2003: Technical Report (ESS Round 1). London: Centre for Comparative Social Surveys.

JOWELL, R. AND THE CENTRAL CO-ORDINATING TEAM (2005). European Social Survey 2004/2005: Technical Report (ESS round 2). London: Centre for Comparative Social Surveys.

KAUFMANN, J. (1994). One person households in Europe. Population 49, 4-5, pp. 935-958

KAUFMAN, G. and GOLDSCHEIDER, F. (2007) 'Do men "need" a spouse more than women? Perceptions of the importance of marriage for men and women'. Sociological Quarterly 48: 29-46. [doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2007.00069.x]

KOHLER, H., BILLARI, F., ORTEGA, J. (2002). The Emergence of Lowest-Low Fertility in Europe During the 1990s. Population and Development Review 28, pp. 641-680. [doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2002.00641.x]

LEVIN, I. (2004). Living apart together: A new family form. Current Sociology 52, pp. 223-240. [doi:10.1177/0011392104041809]

LEWIS, J (2001).The End of Marriage, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

MACFARLANE, A. (1978).The Origins of English Individualism: the Family, Property and Social Transition Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

MCNAY, L. (2000). Gender and Agency: Reconfiguring the Subject in Feminist and Social Theory Cambridge: Polity.

MACPHERSON, C.B. (1962).The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke Oxford: Oxford University Press.

MACVARISH, J. (2006).What is 'the Problem' of Singleness?', Sociological Research Online, 11 (3). [doi:10.5153/sro.1418]

MARKS, N. D. (1996). Flying solo at midlife: Gender, marital status, and psychological well-being. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, pp. 917 –932. [doi:10.2307/353980]

MARSIGLIO, W., HUTCHINSON, S. and COHAN, M. (2001) 'Young Men's Procreative Identity: Becoming Aware, Being Aware, and Being Responsible'. Journal of Marriage and the Family 63: 123-135. [doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00123.x]

O'BRIEN, M. and SHEMILT, I. (2003) Working fathers: earning and caring. Manchester: EOC.

O'BRIEN, M. and JONES, D. (1995) 'Young people's attitudes to fatherhood' in Moss, P. (ed.) Father Figures: Fathers in the families of the 1990s Edinburgh: HMSO.

PAHL, R. E. AND SPENCER, L. (2004). Personal Communities: not simply families of 'fate' or 'choice'. Current Sociology, 52,pp. 199-221. [doi:10.1177/0011392104041808]

REYNOLDS, J. WETHERELL, M AND TAYLOR, S. (2007) Choice and Chance: negotiating agency in the narrative of singleness. The Sociological Review 55, pp. 331-251. [doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2007.00708.x]

REYNOLDS, J. AND WETHERELL, M. (2003). The Discursive Climate of Singleness: The Consequences for Women's Negotiation of a Single Identity. Feminism and Psychology, 13, pp. 489-510. [doi:10.1177/09593535030134014]

ROSENEIL, S. AND BUDGEON, S. (2004). Cultures of Intimacy and Care Beyond 'the Family': Personal Life and Social Change in the Early 21st Century', Current Sociology, 52, pp. 135-159. [doi:10.1177/0011392104041798]

ROSENEIL, S. (2006).'On Not Living with a Partner: Unpicking Coupledom and Cohabitation' , Sociological Research Online 11.

SANTORE, D. (2008) 'Romantic Relationships, Individualism and the Possibility of Togetherness: Seeing Durkheim in Theories of Contemporary Intimacy'. Sociology 42: 1200-1217. [doi:10.1177/0038038508096941]

SHARP, E. AND GANONG, L. (2007).'Living in the Gray: Women's Experiences of Missing the Marital Transition' Journal of Marriage and the Family 69, pp. 831-844 [doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00408.x]

SIMPSON, R. (2006). The Intimate Relationships of Contemporary Spinsters. Sociological Research Online 11 (3) [doi:10.5153/sro.1422]

SIMPSON, R. (2005) Contemporary Spinsterhood in Britain: Gender, Partnership Status and Social Change, PhD thesis, University of London.

SKOLNICK, A. (1991) Embattled Paradise: The American Family in an Age of Uncertainty. Basic Books, New York

SMART, C. (2007) Personal Life: New Directions In Sociological Thinking, Cambridge : Polity

SPENCER, L. AND PAHL, R.(2006) Rethinking Friendship: Hidden Solidarities Today. Princeton University Press.

STACEY, J. (1990). Brave New Families: Stories of Domestic Upheaval in Late Twentieth Century America. NY: Basic Books.

STACEY, J. (1996). In the Name of the Family: Rethinking Family Values in the Postmodern Age. Boston: Beacon Press.

THERBORN, G. (2004). Between Sex and Power: Family in the world 1900-2000. NY: Routledge.

TRIMBERGER, E. KAY (2005).The New Single Woman. Boston: Beacon Press.

TRINDER, L., BECK, M. and CONNOLY, J. (2002) Making contact: how parents and children negotiate and experience contact after divorce York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

WARIN, J., SOLOMON, Y., LEWIS, C. and LANGFORD, W. (1999) Fathers, Work and Family Life. London: Family Policy Studies Centre.

WASOFF, F. and JAMIESON, L. (2005a).Solo-living Across the Adult Lifecourse: Full Research Report. ESRC End of Award Report, RES-000-22-0531, Swindon: ESRC.

WASOFF, F., JAMIESON, L AND SMITH. A. (2005b). Solo-living, Individual and Family Boundaries across the adult lifecourse in McKie, L and Cunningham-Burley, S (eds) Families and Society: Boundaries and Relationships. Bristol: Policy Press

WIGHT, D. 1994. 'Boys Thoughts and Talk about Sex in a Working-Class Locality of Glasgow'. Sociological Review 42: 702-737.

WIGHT, D. 1996. 'Beyond the predatory male' in Adkins, L. and Merchant, V. (eds.) Sexualizing the Social: Macmillan.

WILLIAMS, M. (2007). Solo-living and Life Course Changes 1991-2001: Full Research Report. ESRC End of Award Report, RES-000-22-1413. Swindon: ESRC

WILLIAMS M., MACONACHIE M., AND CHANDLER, J. (2004).Baseline Study of Solo-Living and Longterm Illness: Full Research Report.. ESRC End of Award Report, RES-000-22-0081. Swindon: ESRC.