Social Capital and Community Building through the Internet: A Swedish Case Study in a Disadvantaged Suburban Area

by Sara Ferlander and Duncan Timms

Södertörn University College, Stockholm; University of Stirling

Sociological Research Online 12(5)8

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/5/8.html>

doi:10.5153/sro.1594

Received: 18 May 2006 Accepted: 2 Sep 2007 Published: 30 Sep 2007

Abstract

The rapid diffusion of the Internet has considerable potential for enhancing the way people connect with each other, the root of social capital. However, the more the Internet is used for building social capital the greater will the impact be on those whose access and/or usage is curtailed. It is therefore important to investigate the impacts of Internet on groups at risk of digital and social exclusion. The aim of this article is to examine how the use of the Internet influences social capital and community building in a disadvantaged area. Quantitative and qualitative data from a case study in a suburban area of Stockholm are used to evaluate the social impacts of two community-based Internet projects: a Local Net and an IT-Café. Each of the projects was aimed at enhancing digital inclusion and social capital in a disadvantaged local community. The paper examines the extent to which use of the Internet is associated with an enhancement of social participation, social trust and local identity in the area. The Local Net appears to have had limited success in meeting its goals; the IT-Café was more successful. Visitors to the IT-Café had more local friends, expressed less social distrust, perceived less tension between different groups in the area and felt a much stronger sense of local identity than non-visitors. Visitors praised the IT-Café as providing a meeting-place both online and offline. The Internet was used for networking, exchange of support and information seeking. Although it is difficult to establish causal priorities, the evidence suggests that an IT-Café, combining physical with virtual and the local with the global, may be especially well suited to build social capital and a sense of local community in a disadvantaged area. The importance of social, rather than solely technological, factors in determining the impact of the Internet on social capital and community in marginal areas is stressed.

Keywords: Disadvantaged Area, IT-Café, Local Community, Local Identity, Local Net, Social Capital, Social Networks, Sweden, the Internet, Trust

Introduction

1.1 The Internet is increasingly becoming a part of everyday life in Western societies (Wellman & Haythornwaite 2002; Wellman 2004; Boase et al. 2006). Computers, communications and social networks have intertwined, making the Internet a part of the household and community (Wellman et al. 2006). The rapid diffusion and use of the Internet has the potential for enhancing the way people connect with each other, the root of social capital: 'the ability of actors to secure benefits by virtue of membership in social networks' (Portes 1998 p. 6).1.2 Most writers are optimistic about the potential of the Internet for increasing social capital in local communities, providing a means for enhancing social interaction, community identity and trust (e.g. Beamish 1995; Schuler 1996; Ferlander 2003; Gaved & Anderson 2006). A minority, however, adopt a more dystopian view, claiming that the use of the Internet may come at the expense of local community (e.g. Nie & Erbring 2000). Doheny-Farina (1996) argues that the Internet might simply provide a means for people to get out of the local community. Nie (2001) argues that although the Internet can foster global interactions, it may also keep people indoors, leading them to neglect interactions in the community. However, Wellman (2002) has noted that the Internet provides a means for bridging the local the local and the global, adopting the Japanes neologism 'glocalization' to describe this facility. He also suggests that the Internet is used as a complement to other forms of communication rather than a substitute.

1.3 Recent studies suggest that the creation of social capital through the Internet principally benefits those already privileged (Zinnbauer 2007). Thus, there is a risk that the diffusion and development of the Internet will create new forms of exclusion and division, with people living in marginal areas being especially vulnerable (Ferlander & Timms 2006).

1.4 The more the Internet is used for developing and maintaining social capital, the greater will the impact be on those whose access and/or usage is curtailed. Castells (2001) has acknowledged this danger: 'In a global economy, and in a network society where most things that matter are dependent on these Internet-based networks, to be switched off is to be sentenced to marginality…' (p. 277).

1.5 Sweden is often cited as being at the vanguard of the Information Society. More than four-fifths of Swedish households have access to the Internet at home. During the first quarter of 2005, 95 percent of all people aged 16-44 and 85 percent of those aged 45-54 reported using the Internet. More than half those aged 16-74 used a computer on a daily basis (Statistics Sweden 2005). At the same time, there remain considerable variations in both access and usage, with those occupying more vulnerable social positions – especially in terms of education, age and ethnicity - or living in deprived communities being at most risk of exclusion (ITPS 2003; Statistics Sweden 2005; Ferlander & Timms 2006). Statistics Sweden (2005) report that less than 89 percent of those with higher education qualificartions have Internet access at home; amongst those leaving with less than an upper secondary education qualification the figure is 67 percent. Among two parent families 93 percent have Internet access at home; among single parent families the figure is 69 percent. 50 percent of women aged over 55 years used the Internet at home in Spring 2005. Given the ubiquity of access the differences are significant and particular interest attaches to efforts to embed the use of the Internet in less advantaged areas and among those occupying disadvantaged positions.

1.6 This paper examines two approaches which share the goal of using the Internet to enhance social capital and community in a relatively marginalised area in Stockholm: a Local Net and an IT-Café. Local Nets are computer networks located in geographically based communities and characterised by a focus on local issues, digital inclusion and community building. The aim is to use the Internet to form an online community, which will enhance offline community (Blanchard 2004). Local Nets generally provide private access to local web pages (and the Internet) in people's homes; IT-Cafés, on the other hand, provide access to the Internet in a public setting. Liff et al. (1998) note that IT-Cafés are usually located in urban settings and provide computer and Internet access alongside café provision. This sets IT-Cafés apart from other community access points, such as those provided in public libraries or schools and it has been argued that the social aspect of IT-Cafés is at least as important as the technological one in determining their impact (Stewart 2000). IT-Cafés can function as informal 'third places' (Oldenburg 1989), providing an arena for both physical and virtual interaction (Ferlander 2003).

1.7 The need for more robust empirical research on local computer initiatives in general, and within disadvantaged areas in particular, has been noted by several writers (e.g. Keeble 2003; Loader & Keeble 2004; Ferlander & Timms 2006; Gaved & Anderson 2006). The relationship between Local Nets and social capital has been widely discussed, but subject to little empirical research (Prell 2003). Even less academic attention has been paid to IT-Cafés (Wakeford 2003). In this study, we aim to examine how the use of the Internet has influenced social capital and community building in a disadvantaged area of Stockholm, which has been the site of both a Local Net and an IT-Café.

Social Capital

2.1 Social capital has become one of the most popular terms in the social sciences (e.g. Bourdieu 1985; Coleman 1988; Putnam 1993; Portes 1998; Lin 2001). Differences in the detailed specification of social capital are apparent between theorists, but the core of the concept rests in the availability of resources which can be accessed through social relationships (e.g. Coleman 1990; Putnam 2000; Woolcook 2001; Ferlander 2003; Ferlander 2007). In one of the most frequently quoted statements, Putnam (1995) defines social capital as 'features of social organization such as networks, norms and social trust that facilitate co-ordination and co-operation for mutual benefit' (p. 67).2.2 Social capital can be grounded in a variety of different network characteristics, relating to such variations as the difference between weak and strong relationships (Granovetter 1973) and between bonding, bridging and linking connections (Woolcook 1998). Strong ties are with people emotionally close to the individual; weak ties are with people emotionally distant. Bonding connections are with people similar to oneself; bridging connections are with people different from oneself. Linking connections can be described as a sub-dimension of bridging connections. Whereas bridging ties span horizontal networks, connecting people of similar status, linking ties span vertical chains, linking people across hierarchical groups. Bridging and linking – cross-cutting - social capital provide access to wide informational support; bonding social capital is more likely to provide emotional and instrumental support. It has been suggested that the former may be crucial for 'moving on', providing access to diverse information and resources (Granovetter 1982). Linking relationships may be especially important for poor and excluded communities (Szreter & Woolcook 2004), as these forms of connections have direct implications for social empowerment (Woolcook 2001). Bonding social capital is crucial for 'getting by', providing a fundamental source of social support and a sense of community. It has also been noted that bonding ties may encourage excessive localisation and social exclusion, cutting people off from the wider society and increasing social segregation (Portes & Landolt 1996; Ferlander 2003).

2.3 Most statements about social capital stress its positive value. Social capital has, for instance, been linked to educational achievement (e.g. Coleman 1988), democracy (e.g. Putnam 1993), economic opportunities (Granovetter 1985) and health (e.g. Kawachi et al. 1997; Ferlander 2007). Low social capital can result in social exclusion, reflecting limited access to resources available through social participation and networking (Ferlander 2003) such as learning, health and economic opportunities (Zinnbauer 2007).

2.4 Putnam (2000) has presented evidence that there was a decline in social capital in the United States during the latter half of the twentieth century. He argues that this period saw a decline in socializing, trusting and joining community organizations. The decline resulted in increased isolation with people paying little attention to their local communities. There has been heated debate about whether a similar erosion has taken place in other societies (e.g. Hall 2002; Offe & Fuchs 2002; Rothstein 2002). Regardless of the temporal trajectory, at any one time there is likely to be an uneven distribution of social capital (e.g. Bourdieu 1985; Putnam 2002). Poorer areas tend to have lower overall levels of social capital than more affluent ones (Ferlander & Timms 2001) and there is a significant variation in the nature of the networks involved, with poorer areas tending to have relatively lower levels of bridging and higher levels of bonding connections than more affluent areas (Woolcook 1998).

2.5 Since it has been argued that social capital generally has a positive value, but may be in decline and is unevenly distributed, it is vital to look at its creation. A weakness of much of the existing research and theory in the field is that much more attention has been paid to the consequences of social capital than to its causes (Glaeser 2001; Field 2003). In order to develop policies designed to enhance social capital, research about its formation is needed. Given that social capital is based upon social relationships, anything that acts as a mechanism for communication can be expected to have an influence on it. It is in this context that the role of the Internet becomes salient.

The Internet and Social Capital

3.1 There is a considerable amount of work concerned with the way in the Internet influences social capital (e.g. Ferlander 2003; Huysman & Wulf 2004; Van Bavel et al. 2004; Best & Krueger 2006). Putnam (2000) describes the relationship between the Internet and social capital as follows: 'Social capital is about networks, and the Net is the network to all ends' (p. 171). The Internet has the potential to create and maintain social capital, through its capacity for facilitating new ways of communication, networking, collaboration and the exchange of information and support. The Internet seems well designed for the creation and maintenance of various forms of social capital, such as strong and weak ties, and both bonding (interest-specific) and bridging (non-local) social capital (Ferlander 2003). According to Wellman & Gulia (1999): 'Computer-supported social networks sustain strong, intermediate, and weak ties that provide information and social support in both specialized and broadly based relationships…' (p. 188).3.2 The Internet, and especially email, is often used to maintain links with existing strong ties, such as close friends and family, complementing other forms of communication. At the same time the Internet expands the range of possible networks, and the creation and maintenance of weak ties appears to be easier online than offline. The Internet also facilitates the search for others sharing specific interests, creating bonding social capital. However, although certain online groups host discussions of particular interest, they also gather diverse people, increasing bridging social capital on many levels (Ferlander 2003). The World Bank (2007) also notes the bridging nature of the Internet: 'Information technology has the potential to increase social capital – and in particular "bridging" social capital, which connects actors to resources, relationships and information beyond their immediate environment' (p. 3). This illustrates the spatial aspect of social capital. Bonding social capital can be based on local connections, and bridging social capital on wider, potentially global, forms of social capital. Davies (2004) points out that 'the medium has the rare ability to support any scale of social group and users can connect to local and non-local networks simultaneously, creating bridges between the two' (p. 4).

3.3 Research in relatively affluent areas, with high pre-existing levels of social capital, has shown that membership in Local Nets tends to be associated with an increased level of social participation, both online and offline (e.g. Hampton 2001; 2003; Kavanaugh & Patterson 2002; Mesch & Levanon 2003). Studies of Netville in Toronto and the Blacksburg Electronic Village have concluded that the Internet has positive effects on social capital, especially weak ties, and community building. However, it has been argued that social capital and community attachment may be a prerequisite for the success of local ICT initiatives (e.g. Putnam 2000; Van Bavel et al. 2004). Kavanaugh and Patterson (2001) argue that the success of the Blacksburg project may have been related to its location in a community with high pre-existing levels of social capital. It remains to be seen whether similar effects are apparent in more disadvantaged areas, with lower initial levels of social capital and a weaker sense of community.

The Case Study

4.1 The case study is located in a multi-cultural suburban area called Skarpnäck, c. 10 kilometers southeast of Stockholm city centre. The area was developed in the mid-1980's, with houses arranged in apartment blocks around central car-free courts. The area has a population of around 8600, including many disadvantaged individuals, such as single parents, residents with a low level of income and residents with a foreign background. In 1998, 28 percent of the residents had a foreign background (foreign citizens born abroad or in Sweden or foreign-born Swedish citizens) and 28 percent were also single parents (of all households with children). In 1999, the median income was 178,000 SEK (cf. 205,200 SEK in the rest of Stockholm) (USK 2000; Ferlander 2003).4.2 The area has been stigmatized in the media, where it has been described as having 'high levels of social problems and criminality'. An article in the main Stockholm newspaper Dagens Nyheter (Bengtsson 1999) is almost apocalyptic:

'Skarpnäck was to be the new suburb where one had learnt from mistakes from older suburban areas. However, ... Skarpnäck is the vision that crashed. The social problems are immense and people are fleeing the area. Still, Skarpnäck is probably only at the beginning of its descent... Today criminality is also a big problem. Of all suburbs Skarpnäck had the highest number of reported crimes per inhabitants in 1996-1997... Nowhere else is the gap between Swedes and foreign citizens as big as in Skarpnäck' (p. 3).

4.3 Another sign of the area's stigmatization is its occurrence in the online Urban Slang website: 'Sweden may not be know for their gansters and ghettos, but Skarpnack be da roughest innan da beznaz. Gypsies will steal your bike and sell it back to ya'.

4.4 According to survey data from the Stockholm Office of Research and Statistics, many residents share the negative perceptions of the area held by outsiders. In 1997, for instance, the local community had the highest numbers of respondents complaining about theft and burglary of any area in the city (Ivarsson 1997). It must be stressed, however, that the qualitative findings in our study show that many residents were happy in the area, completely disagreeing with the negative perceptions propagated by outsiders.

The Local Net and the IT-Café

5.1 The Local Net, Skarpnet, was launched in 1998 by the main housing association in the area, with the explicit aim of tackling local social problems. It was one of the first Local Nets in Sweden and received considerable positive attention in the media. Skarpet was run by a single enthusiast – an IT-manager from the housing company – with no local management committee (although it was intended that a number of volunteers living in the area would be appointed as 'ambassadors' to demonstrate the system and provide general help). The site was monitored and the administrator insisted that all communications should be in Swedish - a significant decision given the number of immigrants and the multiplicity of languages spoken in the area.5.2 The initiative aimed to provide subsidised connection to a local website (and to the Internet) at home for all residents in the area, providing access to local (and global) services, such as information about local events and the opportunity to 'chat' with local politicians. Access to the Local Net was free; access to the Internet was based on the same tariff as dial-up services. Skarpnet was mounted on a pre-existing 2Mbits cable network, enabling the telephone to be used while surfing, and was intended to be accessed through user-friendly set-top boxes. These features were unusual in 1998. Despite these advantages, the project failed to achieve critical mass. It was abandoned two years after its inauguration. In its place, an IT-Café was established.

5.3 The IT-Café opened in 2000, located in the 'Culture House', on the main thoroughfare of the area. It was managed by a relatively young local resident well-known in the area. This manager personifies the 'public figure' described by Jacobs (1961) – an individual who is prominent at circulating information and at brokering introductions. In contrast to the single authority behind the Local Net, the IT-Café was sponsored by a combination of the three main housing associations in the area, the local council and an Internet provider. Visitors to the IT-Café were offered subsidised access to 13 computers and the Internet, with, if needed, informal IT-support and help from the manager. The prices were low: 10 SEK for half an hour (c. 1 euro) and 100 SEK for a monthly membership card, which gave unlimited access during the opening hours of the Café. In addition to the equipment, the IT-Café offered a variety of subsidised computer courses for its visitors, including ones specially designed for elderly users. In the coffee area just outside, users could - and did - meet and chat face-to-face.

5.4 The prospectus for the Local Net included the intention of increasing digital inclusion, improving the reputation of the area, enriching social contacts and enhancing the sense of local community. The IT-Café had similar aims, explicitly aiming to decrease the digital divide and increase social integration in the area. Whereas the Local Net mainly focused on building social capital and local community through the creation of a local online community, the IT-Café focused on increasing social interation – online and offline – through the provision of a physical meeting place. On the web site of the IT-Café, the following aims were stated: 'To increase knowledge about the new media and to create a place where people, old and young and from different nationalities, can meet and in that way increase communication between people in the area'.

5.5 In short, each of the initiatives was explicitly aimed at combating the digital divide and at enhancing social contacts and social cohesion in the area. This article focuses on the two latter goals of the projects: to increase social capital and a sense of local community (for an evaluation of their effects on digital inclusion, see Ferlander & Timms 2006).

Research Methods

6.1 The question examined in this paper is: To what extent can the use of the Internet (re-) create social capital and a sense of local community in a disadvantaged urban area? More specifially, we will focus on the impacts of the projects on social contacts, trust, tensions between different groups and a sense of local identity. Computer usage, attitudes and expectations of the projects will also be examined.6.2 The evaluation of the two computer schemes involved a mix of quantitative and qualitative approaches, with questionnaire surveys being supplemented by in-depth interviews and focus groups. Two different comparisons were made in terms of the social impacts of the projects: one cross-sectional and one before and after study.

Questionnaires

6.3 The sample population for the Local Net survey consisted of tenants of the housing association setting up the scheme. The sample frame contained 400 tenants: 200 randomly selected tenants (out of 1000) not connected to the network and the 200 who were connected. Questionnaires were distributed in early 1999. Responses were obtained from 177 residents: 90 who were not connected to the Local Net and 87 who were. Information on those using the IT-Café was obtained from 94 questionnaires placed in the Café in early 2001, with 61 being filled in by visitors (from an unspecified numbers of users). Questionnaires were also delivered to 90 visitors who at some point had bought membership cards: 33 were returned. The IT-Café sample was compared with the samples collected before its opening: the 87 respondents connected to the Local Net and the 90 respondents who were not connected.

6.4 The response rate in the Local Net study was 45 percent. This rate is regarded as reasonably satisfactory, given the high mobility and number of different languages spoken in the area. Many surveys had also recently been conducted in the area, which led to a degree of 'survey resistance'. Comparisons with statistics from the Stockholm Office of Research and Statistics (USK) suggest that the Local Net and the IT-Café samples were generally representative of the overall characteristics of the community population (USK 2000). The Local Net sample is representative in terms of number of years spent in the area, gender and ethnicity. The non-connected sample is also representative in terms of education and ethnicity. The IT-Café sample is representative of the overall population in terms of education and ethnicity.

6.5 The Local Net questionnaires contained approximately 50 questions (the IT-Café survey was slightly shorter), divivided into the following topics: demographic factors, computer experience, patterns of ICT usage, perceptions of the ICT projects, social networks, social support, trust and sense of community. In this article, social capital is measured through questions about social contacts and trust. The sense of local community is measured through questions about tensions between different groups and a direct question about the strength of a feeling of local identity.

6.6 Social contacts were measured through the following question: 'How many really close friends do you have (a close friend is someone you can talk to with about everything)?' There were two response alternatives: 'Close friends in the local area' and 'Close friends outside the area'. Trust was measured using the Srole anomia-scale (Srole 1956), including the key question: 'These days you don't really know whom to trust.' Sense of local community, the second goal of the two projects, was measured through questions about social integration and community attachment: 'Do you believe there is tension between different groups?' 'If you think there is tension, which groups are you thinking about?' and 'To what extent do you feel "locally anchored" and rooted in the area where you live? (State your level of rootednes on this scale from 0, no roots, to 10, very strong roots)'. The latter question has been used in previous surveys (Ivarsson 1990; 1993; 1997; 2000), adding a comparative element.

6.7 Bonding, bridging and linking social capital was measured in geographical terms as well as in more traditional social terms. The first question, concerning number of close friends, measured social capital based upon strong social ties, but simultaneously tapped into the local and non-local dimensions of social capital. The geographical distinction was between local and non-local friends: social contacts within the area (bonding social capital) were compared with those outside the local area (bridging or linking social capital). Within the area, bonding and bridging social capital were investigated through questions about social integration (tensions between different groups) and the sense of local identity. This dimension, community attachment, is according to Wellman and collagues (2001) an important form of social capital. For an explicit discussion about the relationship - and differences - between social capital and community, see Ferlander (2003).

6.8 There is a growing discussion about the measurement of social capital, especially the differences between bonding, bridging and linking social capital. Although social capital is often seen as a multidimensional concept, most empirical studies rely on one-dimensional measures. The most common indicators are membership of voluntary associations and generalized trust. Social connections with family and friends are other common indicators of informal forms of social capital. In this study, we have used indicators that have been used in many previous studies of social capital, but we do not claim to encompass all the dimensions of the concept. The development of empirical indicators, especially ones which can distinguish between bonding, bridging and linking forms of relationships, should be a priority for future research. For a further discussion on the measurement of social capital, see Ferlander (2003; 2004; 2007).

Interviews and Focus Groups

6.9 Data from the questionnaires were enhanced by qualitative information obtained in in-depth interviews and focus groups. Interviews and discussions were primarily conducted in Swedish, with translations provided by the authors. Eleven residents (connected and non-connected) and key people in the Local Net project, including the two ambassadors and the project manager, were interviewed in the first study. These interviews were mostly conducted in 1999. In 2000-2, nineteen current or previous users of the IT-Cafe´ along with the IT-Cafe´manager were also interviewed (in individual interviews or focus groups).

6.10 The respondents for the in-depth interviews and the members of the focus gropus were selected by natural choice or snowball sampling. About half of the in-depth interviews, the ones conducted with 'key-people', such as the project managers, were selected by natural choice. The rest of the interviews were mainly conducted with residents connected to the Local Net. The sample frame used for the focus groups was a list of visitors who at some point had bought membership cards at the IT-Café. The rest of the participants were selected by 'snowball sampling'. According to Gilbert (1993), snowball sampling is suitable 'when the target sample members are involved in some kind of network with others who share the characteristic of interest' (p. 74). For a further description of sampling and methodological issues, see Ferlander (2003; 2004).

Findings

7.1 Despite its good intentions, positive press coverage and the support of the housing company, the Local Net largely failed to achieve its objectives, having a minimal impact on social capital and community in the area. In contrast, the IT-Café appears to have been much more successful, with those making use of the Café exhibiting significantly enhanced levels of social capital and sense of community, as well as making use of the Internet and the IT-Café for a variety of social activities, such as networking, exchange of support and information seeking.The Local Net

7.2 Even at its peak, there were relatively few people connected to the Local Net and most of them can be described as traditional computer users - young, well-educated males (Ferlander 2003; Ferlander & Timms 2006).

Computer Usage

7.3 Even among those who were connected, there was little usage of the local network. Technical problems affected both the broadband cable and the set-top boxes (which were eventually replaced by standard PC's). Although neither setback was long lasting, each helped to erode confidence, especially among less experienced users. A more serious shortcoming was the paucity of local content and the relative absence of attractive services. The shortcomings were clear to interviewees:

Anders (48): 'This net is so incredibly limited… there is not much information on it… The site is damn boring!'Thomas (31): 'I want to meet people online, but there is nobody there… So far I think it's pretty dead with this project – except that the connection is very fast.'

Magnus (54): 'I don't visit Skarpnet very often. Sometimes I go there, but it has not really started.'

7.4 Notwithstanding the relative lack of use, residents were enthusiastic about the potential of the Local Net for local engagement. The facility that was anticipated most eagerly was the provision of local information. At the same time, many residents were interested in and did use Skarpnet as a means of getting access to the Internet. The absence of relevant local material led to the Local Net becoming primarily a gateway to the outside world. Many respondents thought that Skarpnet could enhance social inclusion for its members, providing external links to the wider society.

Impacts on Social Capital and Local Community

7.5 Under these circumstances it is not surprising that the Local Net appears to have had little impact on social capital in the local community. There were few significant differences between residents connected and those not connected to the Local Net in terms of number of close friends, trust and perceived tensions between different groups.

7.6 The findings show that the residents - connected as well as non-connected to the Local Net - had low levels of social capital in 1999. They had few close friends locally and the area was characterised by high levels of distrust and perceived tension between different groups, especially in relation to ethnicity and age. Respondents showed significantly lower levels of local identity than those surveyed in other areas of Stockholm (Ivarsson 1997; Ferlander 2003). A major contributing factor to the low level of social capital, according to the discussions in the focus groups, was the lack of local services and meeting-places in the area.

7.7 One of the few differences between the connected and the non-connected residents was in terms of their sense of local identity. Residents connected to the Local Net expressed a stronger sense of local identity than those who were not connected. This may be related to the project aim to offer a local service in an otherwise rather deprived area. The Local Net was advertised as providing a virtual meeting-place where residents could deal with local issues.

Attitudes and Expectations of the Local Net

7.8 Despite lack of local usage and the limited impact on the local community, most respondents remained positive about the Local Net initiative. Almost three-quarters of those surveyed (73 %) – connected and non-connected - were positive towards the project and very few were negative (4 %). The expectations about the potential of the Local Net as a means for enhancing social capital were also high, among both the connected and the non-connected. About a third of the samples – with no difference between the two groups - thought the Local Net had the potential to increase social contacts, trust and the sense of community in the area, even if it had failed to do so in its operation. Reasons given for believing it could have a positive effect included its potential for enhancing social contacts (34 %), social cohesion (32 %) and local identity (34 %). More than half of the respondents (58 %) believed that Skarpnet would enhance the reputation of the area. Few respondents thought otherwise.

7.9 There were few differences in expectations between those connected and those not connected to the Local Net. However, the connected respondents were more positive about the potential impact of Skarpnet on local identity than the non-connected (42 % versus 25 % thinking it would enhance the identity of the area). Conversely, they were less positive in terms of their expectations about its likely impact on social contacts in the area, with 27 percent of the connected thinking it would increase contacts compared with 43 percent of the non-connected. Some interviewees thought that this was because not everyone was interested in using the Local Net for the creation of social contacts:

Anders (48): 'They (residents) are only interested in the fast connection (to the Internet), so they can do what ever they want.'Magnus (54): 'Skarpnet won't make it become like Italy here in Skarpnäck. Swedes are pretty difficult. You have to attract them somehow. However, the network could be good for increasing contacts between different groups, as you don't know whom you are talking to.'

7.10 Despite being negative, the last interviewee suggested that the Local Net had the potential to increase social integration and bridging social capital in the community. Another resident connected to Skarpnet also thought it had the potential to build bridges between different local groups:

Thomas (31): 'I believe a Local Net could create meetings in the area. The good thing with IT is that one can be anonymous and not judge anyone due to gender, ethnicity etc. There are no prejudices online. Through a Local Net people might realise that they should meet face-to-face, and if they live in the same area that can create really "cool" meetings, for example between an immigrant and a racist. When they eventually meet they cannot say: "What – is it you? Get lost!"'.

The IT-Café

8.1 In contrast to the limited use made of the Local Net, the IT-Café had a regular number of daily users including many visitors from disadvantaged groups, such as elderly people, single parents and people with a foreign background (Ferlander 2003; Ferlander & Timms 2006).Computer Usage

8.2 Not surprisingly, the prime reason quoted by respondents for visiting the IT-Café was access to computers and the Internet. There were also a number of important ancillary reasons, often stressing social aspects of the IT-Café experience such as the availability of informal computer support, the provision of subsidised courses and the chance to meet people and share experiences. Online social activities, such as email and chat, were very popular, in particular among younger users. Among this group, the Internet seemed to complement other forms of communication among people who already had established strong ties, but were able to use the Internet as a means of extending them outside the local community. As put by three of the visitors:

Lucia (22): 'Thanks to email I can keep in touch with my friends in Italy.'Ashmed (27): 'I use email to keep in touch with friends, partly from Skåne (south of Sweden) where I'm from and also with some who have moved abroad.'

Ricardo (21): 'I mainly email my friends and my girlfriend who lives in Umeå (north of Sweden).'

8.3 Among visitors with a foreign background, the Internet was used for seeking news and, as stated in one of the quotes above, contacts 'back home': foreign-language news pages were a popular download. In addition to the use of email for maintaining connections with family and friends, the Internet was used for making new links. It was appreciated for its potential to open up new contacts with different types of people from all over the world and also for the chance of meeting people sharing similar interests:

Eva (48): 'You have a greater range for meeting people from the whole country and from other countries.'Julio (24): 'I chat with girls from different parts of Sweden, like Umeå or Gävle.'

Athena (26): 'I often chat in foreign chats. I love to chat with people that I don't know - just because many of them are different to me... I have not made any friends, friends, but I have definitely expanded my social network. '

Shazia (38): 'It is very easy to get contacts. The world becomes so small. You can go everywhere and find people with the same interests.'

8.4 In general, the Internet was especially valued for its facility for reaching the outside world, creating bridges between what is recognised as being a disadvantaged area and the wider society. Many visitors stated that they felt more included in the Information Society and the wider society as a result of using the IT-Café.

Impacts on Social Capital and Local Community

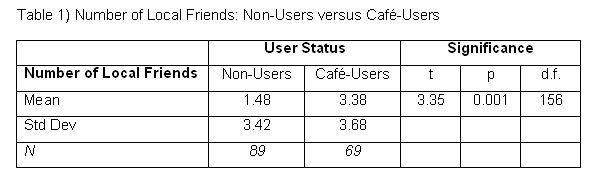

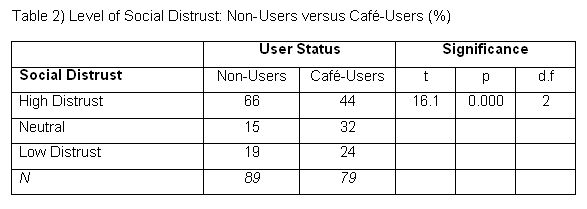

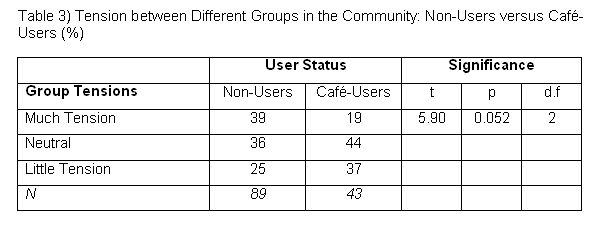

8.5 The findings show that social capital and a sense of local community were significantly higher among IT-Café users than among the residents surveyed two years earlier. Visitors to the IT-Café reported having significantly more local friends, expressed less social distrust, perceived less tension between different groups and felt a stronger sense of local identity than the earlier respondents. USK data (Ivarsson 2005) suggest that there was no general increase in the social capital indicators for Skarpnäck during this time, indicating no major changes in the local community between the first and the second study: IT-Café visitors were clearly distinctive.

|

8.6 Table 1 shows that respondents visiting the IT-Café reported twice as many friends in the local community as non-visitors (3.4 vs. 1.5). It may, of course, have been the case that the IT-Café attracted those who were already gregarious, but participants in the focus groups suggested that the difference reflected the meetings that took place in the IT-Café, with contacts being created and maintained in the Café online as well as offline:

Manager: 'I think the Café can lead to new contacts... People may sit here in the Café, perhaps talk and later say "hi" to each other in the street.'Jurgita (47): 'People socialise in the Café. I have seen that. And my children have met other children here.'

|

8.7 Table 2 shows significant difference between IT-Café visitors and non-visitors in terms of trust. As measured by questions from the Srole anomia scale (1956), people who visited the IT-Café tended to have a lower level of generalized social distrust than those who did not visit: less than half the IT-Café users (44 %) agreed that 'You do not really know whom to trust these days', compared with two-thirds of the non-users. Possible reasons for the lower levels of distrust among the Café-visitors identified in the interviews and focus groups included meetings with members from different groups in the Cafe, providing a non-threatening perspective on social heterogeneity, and the range of information on different cultures available on the Web. One visitor explained it like this:

Birgitta (59): 'You get a feeling that the people who come here are pretty decent... When you come in here, without thinking about it, you take it for granted that the people are pretty decent. This may increase general trust in the whole area.'

|

8.8 As shown in Table 3, there was a significant difference between Café-users and non-users in terms of their perception of tensions in the community. Non-users were much more likely to specify conflict than users of the IT-Café, quoting both inter-generational and inter-ethnic tensions. About two-fifths of the non-users (39 %) thought that there was tension between different local groups compared to only about one fifth in the IT-Café sample (19 %). As in the case of mistrust, focus group participants and interviewees suggested that the reason for there being less perceived tension in the community among Café users was related to the non-threatening meetings between different groups which took place in and through the IT-Café. Several respondents mentioned the mutual respect between people with different backgrounds, facilitated by the Café:

Katitzi (26): 'I have got in touch with many people in the Café. If you sit here you naturally talk to other people – different people: immigrants, Swedes, older people, youngsters... It's important that there is something – a kind of meeting place for everyone. Not just a youth club or something only for the mentally ill. This is something for everyone.'Greta (81): 'Today the girl next to me has helped me. We've become friends. They're so sweet these young people.'

Manager: 'I feel touched when I see a youngster helping an elderly person or when an immigrant asks straight out in the room about the spelling of a word. These things happen here in the IT-Café, and I definitely think that the Café integrates people in the area.'

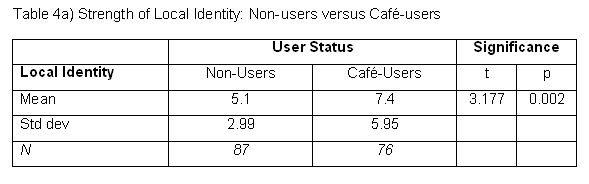

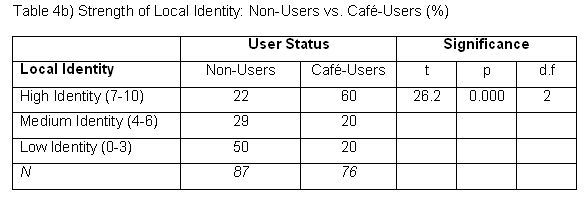

8.9 One of the major differences between IT-Café visitors and those questioned two years earlier is the strength of local identity. Visitors to the Café expressed a much stronger sense of local identity than non-visitors.

|

8.10 Table 4ª demonstrates that before the opening of the IT-Café, in 1999, the sense of local identity in the area was low: 5.1 on a scale from 1 (no local identity) to 10 (very strong local identity). Using the same question, the Stockholm Office of Research and Statistics found that the average score among residents in the area has been low, slightly over five, for the previous 5-10 years (Ivarsson 1990; 1993; 1997; 2000). This compares with an average of 6.7 in Stockholm as a whole, and is one of the lowest scores in the Metropolitan area. The mean on the identity scale for IT-Café-visitors in 2001 was 7.4, significantly higher than the figure recorded for non-users two years earlier - and, indeed, above the average for Stockholm as a whole. On this measure of local community, the IT-Café appears to have been especially successful.

8.11 As Table 4b shows, far more IT-Café respondents (60 %) felt a strong sense of local identity (score 7+) than non-users of the Café (22 %). Conversely, only a fifth (20 %) of the IT-Café sample felt a low level of local identity, compared to half (50 %) of the non-users.

|

8.12 Visitors to the IT-Café were clearly exceptional, expressing a much stronger sense of local identity than non-visitors. Interviews and focus group responses suggested that the IT-Café played a significant causal role in encouraging local pride and identity, acting as an informal physical and virtual meeting place. As three focus groups participants put it:

Athena (26):' I think it was a super idea. This area needs an IT-Café instead of cutting down everything important here. It is important that there is something – a kind of meeting-place for everyone. And computers are something everyone needs now.'Jurgita (47): 'If you compare with other areas, they don't have IT-Cafés. You cannot surf on the Internet there.'

Greta (81): 'I think the Café increases the standard in the whole area. Absolutely.'

Attitudes and Expectations

8.13 The survey data shows that attitudes towards the IT-Café and expectations of its impact in terms of social capital and community building were very high – significantly higher even than those stimulated by the Local Net. Almost everyone surveyed was positive toward the IT-Café (98 %) and nobody was negative (cf. Local Net: 73 % and 4 %). More than two-thirds of respondents thought the IT-Café had already enhanced social capital in the area, with 70 percent saying that it had encouraged social contacts (cf. 27 % of those connected to the Local Net). Users also believed that the Café would increase the sense of local community, with 66 percent saying that it would enhance local identity and 48 percent that it would have a direct impact on social cohesion (cf. Local Net: 34 % and 32 %). The vast majority of respondents (80 %) thought the area would become more attractive as a result of the IT-Café (cf. 58 % of those connected to the Local Net).

Discussion

9.1 The basis of social capital is connectivity. Anything which has an effect on the ability of people to connect with others is likely to play a crucial role in the development of social capital. To the extent that opportunities are opened up for people to meet with others in a context which encourages networking, trust, mutual respect and local identity, social capital will be enhanced. Both the Local Net and the IT-Café reviewed here sought to provide just such a context.Summary of Results

9.2 Skarpnet failed to reach most of its stated goals. Despite the widespread interest in using it for local purposes and high expectations, technological problems in combination with a lack of local services led to little local usage and the impact on local participation and levels of trust in the local community was insignificant. The Local Net was more successful in terms of facilitating networking outside the local area, fostering bridging and linking forms of social capital. The few users of the Local Net mainly used it as a gateway to the Internet, reflecting the concern expressed by Doheny-Farina (1996) that Local Nets might simply provide means for local residents to 'get out of town'. Although not reaching its goals in terms of local usage and the creation of local or bonding social capital, the role of the Local Net in building links to the wider society was a potentially significant achievent in terms of social inclusion and social empowerment. These are important aspects for people in a disadvantaged area (Szreter & Woolcook 2004), but the demise of the project meant that this potential could not be pursued.

9.3 In contrast to the Local Net, the IT-Café seems to have met virtually all its goals: attracting many visitors from disadvantaged groups, notably pensioners and immigrants, and encouraging a general increase in computer-skills, increasing both digital and social inclusion (Ferlander & Timms 2006). The IT-Café also appears to be related to an enhancement of several indicators of social capital in the local community. Users of the IT-Café had significantly more local friends, higher levels of trust and a stronger sense of social cohesion and community identity than the non-visitors surveyed earlier.

9.4 The IT-Café provided a physical meeting place which faciliated social networking, especially the development of weak ties bridging different local groups, and led to decreased tensions between them. The physical aspect of the IT-Café had positive impacts upon local ties and bonding social capital. Nonetheless, visitors to the Café, in common with the users of the Local Net, mainly used the Internet for non-local networking (bridging and linking social capital) including the creation and/or maintenance of both weak and strong, and interest-specific (bonding) ties. The Internet was used for the maintenance of non-local strong bonding social capital, with many visitors using the Internet to keep in touch with family and friends outside the local community. People with a foreign background kept in touch with people in their home countries via email and used the Internet to search for relevant information such as foreign newspapers. The IT-Café facilitated social participation among its visitors at both local and global scales: 'glocalization' personified (Wellman 2002). The Internet was used for the creation and maintenance of diverse forms of social capital spanning geographical and social boundaries (Wellman & Gulia 1999; Ferlander 2003).

9.5 As is generally the case in synchronous research, it is difficult to disentangle causal priorities in the present study. It can be argued that visitors to the IT-Café already had high levels of local social connections and a strong sense of local community beforehand: visitors to local meeting-places tend to be people who are already socially engaged and they might, indeed, have been attracted to the Café through local acquaintances. Although this possibility cannot be excluded, respondents in the focus groups and interviews were adamant that the IT-Café had had a marked and positive effect on the development of social contacts, the growth of mutual understanding and trust and the sense of local identity. Respondents believed that none of these would have occurred if the IT-Café had not existed.

Criteria for Successful Social Capital and Community Building Internet Projects

10.1 It is dangerous to generalize from a single case, but it seems that the IT-Café was rather effective in terms of enhancing social capital and building community, while the Local Net was much less successful. The differing impacts of the Local Net and the IT-Café highlight the importance of social factors in building social capital and community in areas with low initial levels of social capital.10.2 There are a number of differences between the Local Net and the IT-Café which may have influenced their relative degrees of success. The difference in the nature and location of access to the Internet is, perhaps, the most obvious distiction between the two projects. Whereas the Local Net depended on individualised, private access in resident's homes, the IT-Café provided public access in a communal space. The Local Net suffered from the lack of face-to-face reinforcement available to the uses of the IT-Café. The physical aspect – a meeting place open for everyone – in itself seems to have been very important for building social capital and community in Skarpnäck.

10.3 The provision of face-to-face support and training was an important factor in the success of the IT-Café. Many digitally excluded groups, especially elderly people, exhibit a lack of interest and confidence in using technology. In order for them to overcome these barriers to participation in the Information Society it is essential to provide support and training. People need both motivation and skills to use the Internet for building community and social capital. The face-to-face support and courses offered in the IT-Café – by the manager and on the basis of self-help by the visitors themselves - played a significant role in increasing visitors' interest and ability to use the Internet for social activities. Skarpnet failed to satisfy this criterion; the IT-Café met it.

10.4 There was also a difference in focus between the two projects. The Local Net focused on building a local online community, the IT-Café focused on providing a physical meeting place where residents could learn about the Internet and and use it to reach the outside world. The emphasis on local issues was stronger in the Local Net than in the IT-Café. Paradoxically this may have been a handicap: it may be more difficult to attract local Internet usage than global usage, especially in disadvantaged areas which are characterised by low levels of social capital and a weak sense of community. For the survival of a Local Net it is crucial to make local online services as attractive as those available elsewhere on the Internet. Without relevant content, based on the needs of the community, Local Nets will not be used for local social capital building. The failure of Skarpnet to attract local material was both a symptom and a cause of its demise.

10.5 The final – and related - difference concerns the management of the two projects. The IT-Café was seen as being a genuinely communal facility; the Local Net was perceived as being primarily the property of the housing company. It is a basic assumption of the community networks movement (Schuler 1996) that for community-based Internet initiatives to be a positive force for the enhancement of social capital and community building they must be rooted in the locality itself. A bottom-up approach, with local residents contributing to the creation and content of the project, is important for its survival. This may however be difficult in a community with low levels of social capital.

10.6 The demise of the Local Net can be interpreted as providing further support for the belief that successful Local Nets, based on home access, demand high and pre-existing levels of social capital and community (e.g. Putnam 2000; Kavanaugh & Patterson 2001). This may be one of the reasons for the difference in outcomes between Skarpnet and the well-known Netville project in an affluent Canadian area (Hampton 2001). More generally, there is likely to be a two-way relationship between the Internet and social capital. The success of the IT-Café indicates that use of the Internet is not inimical to the enhancement of social capital and that, given the right social context, it can enhance both local and wider forms of social capital. The ability to combine online with offline and the local with the global, is of especial relevance for the creation of social capital in disadvantaged local communities. How to use the Internet for social capital and community building in disadvantaged areas is a topic that warrants further investigation.

Postscript

11.1 The success of the IT-Café was closely linked with the role played by its manager and his success in obtaining funding and local political support. In 2004, the manager left the Café and funding was reduced. In the light of this, the management committee, representing both users and funders, introduced a number of changes in the operation of the Café. These involved closer integration with the other activities taking place in the Culture House and a concentration on audio-visual activities. The new centre, the Mediaroom, is open on a more resticted basis than the old Café – three afternoons a week. Its web site invities residents in Skarpnäck to 'Come and make films, surf, study or why not email local politicians?'11.2 The community-building activities associated with the IT-Café are being continued in the Fältprojekt. This was set up in March 2003 following a series of meetings in the IT-Café and involves both local volunteers and the two main housing associations in Skarpnäck. The fältprojekt aims 'to improve residents' feelings of security and community, to increase local democracy, and to facilitate the development of strong social networks anchored in the locality'. The project has set up ten neighbourhood groups (Gårdarna), each of which has its own website. The project fulfils many of the aims originally set out in the prospectus for Skarpnet, including the provision of information on local clubs and activities, facilities for local meetings and political action addressing local issues. The successful establishment of the neighbourhood groups stands as a testament to the lasting impact of the IT-Cafe on social capital in Skarpnäck.

Acknowledgements

This research has been funded by the Department of Psychology, University of Stirling, and three different EU Projects: SCHEMA (Social Cohesion through Higher Education in Marginal Areas), ODELUCE (Open and Distance Education and Learning through University Continuing Education) and the UNIVe Project. The authors would also like to thank Professor John Field, University of Stirling, for his comments on an earlier draft. Finally, we would like to thank those residents who participated in the study for their time and valuable contributions.

References

BEAMISH, A. (1995) Communities On-Line: Community-based computer networks. Master's Thesis, Department of Urban Studies and Planning. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.BENGTSSON, J. (1999) 'Skarpnäck – Visionen som kraschade. Dagens Nyheter 991103.

BEST, S.J. and KRUEGER, B.S. (2006) 'Online Interactions and Social Capital: Distinguishing between new and existing ties', Social Science Computer Review, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 395-410.

BLANCHARD, A. (2004) 'The Effects of Dispersed Virtual Communities on Face-to-Face Social Capital' in M. Huysman and V. Wulf (editors) Social Capital and Information Technology. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

BLANCHARD, A. and HORAN, T. (1998) 'Virtual Communities and Social Capital', Social Science Computer Review, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 293-307, <http://www.idea-group.com/downloads/excerpts/garson.pdf>.

BOASE, J., HORRIGAN, J.B., WELLMAN, B. and RAINIE, L. (2006) The Strength of Internet Ties. Washington, D.C.: Pew Internet & American Life Project, <http://www.pewinternet.org/PIP_Internet_ties.pdf>.

BOURDIEU, P. (1985) 'The Forms of Capital' in J.G. Richardson (editor) Handbook for Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. New York: Greenwood.

CASTELLS, M. (2001) The Internet Galaxy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

COLEMAN, J. (1988) 'Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital', American Journal of Sociology, Issue Supplement, pp. S95-120.

COLEMAN, J. (1990) Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

DAVIES, W. (2004) Proxicommunication - ICT and the Local Public Realm. iSociety report. London: The Work Foundation, <http://www.theworkfoundation.com/research/isociety/proxi_main.jsp>.

DOHENY-FARINA, S. (1996) The Wired Neighborhood. New Haven: Yale University Press.

FERLANDER, S. (2003) The Internet, Social Capital and Local Community. Doctoral Dissertation. Stirling: University of Stirling, <http://www.crdlt.stir.ac.uk/publications.htm>.

FERLANDER, S. (2004) 'E-learning, Marginalised Communities and Social Capital: A mixed method approach' in M. Osborne, J. Gallacher & B. Crossnan (editors) Researching Widening Access to Higher and Further Education: Issues in international research. London: Routledge.

FERLANDER, S. (2007) 'The Importance of Different Forms of Social Capital for Health', ACTA Sociologica, Vol. 50, No. 2, pp. 115-128.

FERLANDER, S. and TIMMS, D. (2001) 'Local Nets and Social Capital', Telematics and Informatics, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 51-65.

FERLANDER, S. and TIMMS, D. (2006) 'Bridging the Dual Digital Divide: A Local Net and an IT-Café in Sweden', Information, Communication & Society, Vol. 9, No 2, pp. 137-159.

FIELD, J. (2003) Social Capital. Key Ideas. London: Routledge.

GAVED, M. and ANDERSON, B. (2006) The Impact of Local ICT Initiatives on Social Capital and Quality of Life, Chimera Working Paper 2006-6, Colchester: University of Essex.

GILBERT, N. (1993) Researching Social Life. London: Sage.

GLAESER, E.L. (2001) 'The Formation of Social Capital', ISUMA, Canadian Journal of Policy Research, Vol. 2, pp. 34-40.

GRANOVETTER, M.S. (1973) 'The Strength of Weak Ties', American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 78, pp. 1360-80.

GRANOVETTER, M.S. (1982) 'The Strength of Weak Ties: A network theory revisited' in P. Marsden and N. Lin (editors) Social Structure and Network Analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

GRANOVETTER, M.S. (1985) 'Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of embeddedness', American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 85, pp. 489-515.

HALL, P.A. (2002) 'Great Britain: The Role of Government and the Distribution of Social Capital' in R.D. Putnam (editor) Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society. New York: Oxford University Press.

HAMPTON, K. (2001) Living the Wired Life in the Wired Suburb: Netville, glocalisation and civil society. Doctoral Dissertation. Toronto: University of Toronto, <http://www.mysocialnetwork.net/downloads/khampton01.pdf>.

HAMPTON, K. (2003) 'Grieving for a Lost Network: Collective action in a wired suburb', The Information Society, Vol. 19, No. 5, pp. 1-13, <http://www.mysocialnetwork.net/downloads/mobilization-final.pdf>.

HUYSMAN, M. and WULF, V. (editors). (2004) Social Capital and Information Technology. Cambridge: MIT Press.

ITPS, SWEDISH INSTITUTE FOR GROWTH POLICY STUDIES (2003) A Learning ICT Policy for Growth and Welfare, ITPS's final report on its assignment of evaluating the Swedish ICT policy. Stockholm: Elanders Gotab.

IVARSSON, J-I. (1990) Medborgarinflytande i Stockholm. Levnadsförhållanden och medborgaraktiviteter i sex stadsdelar. Utredningsrapport 1990:4. Stockholm: USK.

IVARSSON, J-I. (1993) Stadsdelsnämndsförsöken i Stockholm – invånarnas reaktioner och synpunkter. Utredningsrapport 1993:3. Stockholm: USK.

IVARSSON, J-I. (1997) Så tycker brukarna om servicen i stadsdelen. Utredningsrapport 1997:3. Stockholm: USK.

IVARSSON, J-I. (2000) Servicen i stadsdelen 1999 – så tycker brukarna, en jämförelse med 1996. Utredningsrapport 2000: 1. Stockholm: USK.

IVARSSON, J-I. (2005) Situation och service in stadsdelen 2005: så tycker brukarna, jämförelser med 1996, 1999 och 2002. Stockholm: USK <http://www.stockholm.se/files/103500-103599/file_103518.pdf>.

JACOBS, J. (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

KAVANAUGH, A.L. and PATTERSON, S.J. (2001) 'The impact of community computer networking on community involvement and social capital.' American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 45, pp. 496-509.

KAVANAUGH, A.L. and PATTERSON, S.J. (2002) 'The impact of community computer networks on social capital and community Involvement in Blacksburg' in B. Wellman and C. Haythornthwaite (editors) The Internet in Everyday Life. Oxford: Blackwell.

KAWACHI, I., KENNEDY, B.P., LOCHNER, K. and PROTHROW-SMITH, D. (1997) ‘Social Capital, Income Inequality, and Mortality’, American Journal of Public Health,Vol. 87, pp. 1491-1498.

KEEBLE, L. (2003) 'Why Create? A Critical Review of a Community Informatics Project', Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Vol. 8, No. 3, <http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol8/issue3/keeble.html>

LIFF, S., FRED, S. and WATTS, P. (1998) Cybercafés and Telecottages: Increasing public access to computers and the Internet. Survey report, Virtual Society? Programme, Economic and Social Research Council, United Kingdom, <http://virtualsociety.sbs.ox.ac.uk/text/reports/access.htm>.

LIN, N. (2001) Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

LOADER, B. and KEEBLE, L. (2004) A Literature Review of Community Informatics Initiatives. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation, <http://www.jrf.org.uk>.

MESCH, G.S. and LEVANON, Y. (2003) 'Community Networking and Locally-based Social Ties in Two Suburban Localities', City & Community, Vol. 14, No. 5, pp. 335-351.

NIE, N.H. (2001) 'Sociability, Interpersonal Relations, and the Internet', American Behavior Scientist, Vol. 45 (3): pp. 420-35.

NIE, N.H. and ERBRING, L. (2000) Internet and Society: A Preliminary Report. Stanford: Stanford Institute for the Quantitative Study of Society (SIQSS), Stanford University, and interSurvey Inc. <http://www.stanford.edu/group/siqss/Press_Release/Preliminary_Report.pdf>.

OLDENBURG, R. (1989) The Great Good Place. New York: Paragon House.

OFFE, C. and FUCHS, S. (2002) 'A Decline of Social Capital? The German Case' in R.D. Putnam (editor) Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society. New York: Oxford University Press.

PORTES, A. (1998) 'Social Capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology', Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 24, pp. 1-25.

PORTES, A. and LANDOLT, P. (1996) 'The Downside of Social Capital', The American Prospect, Vol. 26, <http://www.prospect.org/archives/26/26-cnt2.html>

PRELL, C. (2003) 'Community Networking and Social Capital: Early investigations', Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Vo. 8, No. 3, <http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol8/issue3/prell.html>

PUTNAM, R.D. (1993) Making Democracy Work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

PUTNAM, R.D. (1995) 'Tuning in, Tuning out: The strange disappearance of social capital in America', Political Science and Politics, Vol. 28, pp. 664-683.

PUTNAM, R.D. (2000) Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon Schuster.

PUTNAM, R.D. (2002) Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society. New York: Oxford University Press.

ROTHSTEIN, B. (2002) 'Sweden: Social Capital in the Social Democratic State' in R.D. Putnam (editor) Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society. New York: Oxford University Press.

SCHULER, D. (1996) New Community Networks: Wired for change. New York: ACM Press. Seattle Community Network. 2004, <http://www.scn.org>.

SROLE, L. (1956) 'Social Integration and Certain Corollaries: An explanatory study', American Sociological Review, Vol. 21, pp. 709-716.

STATISTICS SWEDEN (2005) Use of Computers and the Internet by Private Persons in 2005. Stockholm: Statistiska centralbyrån

STEWART, J. (2000) 'Cafematics: Cybercafés and the Community' in M. Gurstein and P.N. Hershey (editors) Community Informatics: Enabling Communities with Information and Communication Technologies. Idea Group Publishing.

SZRETER, S. and WOOLCOOK. M. (2004) 'Health by Association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health', International Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 33, pp. 650-667.

THE WORLD BANK (2007) 'Social Capital and Information Technology', <www.worldbank.com>

USK (2000) Områdesfakta. Available at: <http://www.usk.stockholm.se/internet/omrfakta>

VAN BAVEL, R., PUNIE, Y., BURGELMAN, J.C., TUOMI, I. & CLEMENTS, B. (2004) ICTs and Social Capital in the Knowledge Society. Report of a Joint DG JRC/DG Employment Workshop. IPTS, Seville, 3-4 November 2003.

WAKEFORD, N. (2003) 'The Embedding of Local Culture in Global Communication: Independent Internet Cafés in London', New Media & Society, Vol. 5, pp. 379-399.

WELLMAN, B. (2002) 'Little Boxes, Glocalization, and Networked Individualism' in M. Tanabe, P. Van den Besselaar and T. Ishida (editors) Digital Cities II: Computational and Sociological Approaches. Berlin: Springer, <http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/~wellman/publications/littleboxes/littlebox.PDF>.

WELLMAN, B. (2004) 'Connecting Communities: On and offline', Contexts, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 22-28.

WELLMAN, B. and GULIA, M. (1999) 'Net Surfers don't Ride Alone', in B. Wellman (ed.), Networks in the Global Village (pp. 331-366). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

WELLMAN, B., HASSE, A.Q., WITTE, J. and HAMPTON, K. (2001) 'Does the Internet Increase, Decrease or Supplement Social Capital? Social networks, participation and community commitment', American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 45, pp. 436-55, revised version <http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/~wellman/publications/netadd/hungarian-article2.PDF>

WELLMAN, B. and HAYTHORNWAITE, C. (2002) The Internet in Everyday Life. Oxford: Blackwell.

WELLMAN, B., HOGAN, B., BERG, K., BOASE, J., CARRASCO, J-A., COTÉ, R., KAYAHARA, J., KENNEDY, T.L.M. and TRAN, P. (2006) 'Connected Lives: The project', in P. Purcell (editor) Networked Neighbourhoods: The connected community in context. Berlin: Springer.

WOOLCOOK, M. (1998) 'Social Capital and Economic Development: Towards a theoretical synthesis and policy framework', Theory and Society, Vol. 27, pp 151-208.

WOOLCOOK, M. (2001) 'The Place of Social Capital in Understanding Social and Economic Outcomes', ISUMA, Canadian Journal of Policy Research, Vol. 2.

ZINNBAUER, D. (2007) What can Social Capital and ICT do for Inclusion?, Institute for Prospective Technological Studies. Seville: European Commission Joint Research Centre.