Sociology and, of and in Web 2.0: Some Initial Considerations

by David Beer and Roger Burrows

University of York; York St John University

Sociological Research Online 12(5)17

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/5/17.html>

doi:10.5153/sro.1560

Received: 14 May 2007 Accepted: 2 Sep 2007 Published: 30 Sep 2007

Abstract

This paper introduces the idea of Web 2.0 to a sociological audience as a key example of a process of cultural digitization that is moving faster than our ability to analyse it. It offers a definition, a schematic overview and a typology of the notion as part of a commitment to a renewal of description in sociology. It provides examples of wikis, folksonomies, mashups and social networking sites and, where possible and by way of illustration, examines instances where sociology and sociologists are featured. The paper then identifies three possible agendas for the development of a viable sociology of Web 2.0: the changing relations between the production and consumption of internet content; the mainstreaming of private information posted to the public domain; and, the emergence of a new rhetoric of 'democratisation'. The paper concludes by discussing some of the ways in which we can engage with these new web applications and go about developing sociological understandings of the new online cultures as they become increasingly significant in the mundane routines of everyday life.

Keywords: Sociology of Web 2.0, Sociology of Digitization, Digtization of Sociology, Social Networking Sites, Sociological Description, Online Cultures

Introduction

1.1 By the time you get to read this paper in its published form, even in the hypertextual pages of Sociological Research Online, what it describes may well have become part of the cultural mainstream. (Keen, 2007) It will be mundane. This is a major challenge for sociology in a world where 'internet time' (Wellman and Haythornthwaite, 2002) now runs at a clock speed several orders of magnitude faster than that of academic research. Sociological reactions to this problem of cultural 'speed-up' broadly fit into one or other of two basic strategies (Gane, 2006). On the one hand, some suggest that the discipline needs to match the speed-up of the world by 'going with the flow' and becoming more 'technologized' (Lash, 2002; Lunenfeld, 2000). On the other hand, and seemingly contrary to this, others suggest that in such times of cultural speed-up the discipline should either call for social and cultural slow-down (McLuhan, 1997; Virilio, 1986; 2000), slow down itself (Baudrillard, 2001; 2002), or perhaps even both. Of these two options we would probably err towards the first. We at least want to attempt to go with the flow. We are of the view that the discipline would do well at the present juncture to follow the lead of writers such as Pickstone (2002), Latour (2005) and Lash and Lury (2007) and embrace a renewed interest in sociological description (Savage and Burrows, 2007) as applied to new cultural digitizations. This means that it is necessary for us to 'technologize' ourselves rather more than has hitherto been the case. At a time of rapid socio-cultural change a renewed emphasis on good – critical, distinctive and thick – sociological descriptions of emergent digital phenomena, ahead of any headlong rush into analytics, seems to us to be a sensible idea. We need to understand some of the basic parameters of our new digital objects of sociological study before we can satisfactorily locate them within any broader frames of theoretical reference.1.2 Our concern here is with a cluster of contemporary networked technologies which, popular rhetoric suggests, are reworking hierarchies, changing social divisions, creating possibilities and opportunities, informing us, and reconfiguring our relations with objects, spaces and each other. If this is indeed the case then they obviously have a huge sociological significance. However, they are also technologies that have very quickly become incorporated within the mundane realities of everyday life (especially for many young people) and, as such, are in danger of quickly sinking from sociological view unless we remain alert to their broader significance (Wellman and Haythornthwaite, 2002).

1.3 Our focus here is on some significant developments in internet culture which have emerged in the last two years or so, but which have so far received little in the way of any sustained sociological investigation. We are interested in trying to ascertain what sociological agendas are relevant to understanding the large scale shift toward user-generated web content – a movement defined by the related practices of (to use the argot of the field) 'generating' and 'browsing', 'tagging' and 'feeds', 'commenting' and 'noting', 'reviewing' and 'rating', 'mashing-up' and making 'friends'. Our concern is to produce some introductory notes for the general sociological reader towards the development of a sociology of (what has come to be known as) Web 2.0 – a supposedly second upgraded version of the web that is more open, collaborative, and participatory (O'Reilly, 2005). Here we use this term – Web 2.0 – simply as an initial sensitising concept, albeit one that we recognise is already contaminated by the rhetorical strategies of web designers, the sales patter of commercial futurists, and the new cultures discourse of the popular media. We use the term simply as a device to refer to a cluster of new applications and related online cultures that possess a conceptual unity only to the extent that it is possible to decipher some significant socio-technical characteristics that they have in common. The Web 2.0 we begin to characterise and describe here is complex, ambivalent, dynamic, laden with tensions and subversions, and, we would argue, of increasing sociological significance.

1.4 The paper is divided into three sections. The first describes Web 2.0 and draws on examples from sociology to introduce and illustrate the applications that are covered; we call this simply sociology and Web 2.0. The second section then moves toward how we might begin to think sociologically about these Web 2.0 applications. We continue to use examples from sociology but the aim of this section is to begin to sketch out a possible sociology of Web 2.0. We then conclude with a discussion of the various ways that we might be able to engage sociologically with these new web applications, how we might get inside these web cultures and use them for sociological purposes (conducting research, finding things out, teaching, and so on). This final section may then be thought of as a brief discussion of sociology in Web 2.0.

Sociology and Web 2.0

2.1 We see through a range of already very well know websites, such as http://www.wikipedia.organd http://www.myspace.com, that networks are taking shared responsibility for the construction of vast accumulations of knowledge about themselves, each other, and the world. These are dynamic matrices of information through which people observe others, expand the network, make new 'friends', edit and update content, blog, remix, post, respond, share files, exhibit, tag and so on. This has been described as an online 'participatory culture' (Jenkins et al., 2006) where users are increasingly involved in creating web content as well as consuming it.2.2 Thus far there has been little systematic research into the activities that are generating this new web content or, indeed, who it is that is involved. However, what has already become clear is that a more active and participatory role is being taken by web users in these developments. Indeed, research from the Pew Internet & American Life project reported as far back as 2005 (a long while ago in 'Internet time') found that 'more than half of all teens who go online create content for the internet' (Lenhardt and Madden, 2005: 8). This is sure to have escalated with the significant rise of content generated Web 2.0 applications and particularly social networking sites (SNS) such as MySpace in the interim. Perhaps the most common user-generated content prior to this explosion was the personal blog or weblog. Blogs are run as spaces where individuals, or groups, write for an online audience. These are often described as online diaries that users frequently update. The types of entries made vary quite considerably and are not always limited to the type of entries that you might expect to see in a diary. So for instance we find sociologists operating sociologically informed blogs where they discuss their work, academic conferences, recent publications, contemporary debates in the discipline and so on. Examples of this include http://www.purselipsquarejaw.org, a blog run by Anne Galloway to communicate her research and activities, and http://www.homecookedtheory.com, a blog run by Melissa Gregg as part of her academic research into blogging. We find now that sociological research on Web 2.0 is being developed through blogging see for instance Maz Hardey's blog at http://properfacebooketiquette.blogspot.com/. Also notable here is the blog http://www.spaceandculture.org that runs alongside the publication of the print journal of the same name. A further note should also be made of the recent foray of the British Sociological Association (BSA) into the world of blogging with their blog accompanying the 2007 Annual conference, http://www.bsaconf.blogspot.com/. In more general terms the importance of blogging is that it became an established practice for creating user generated content and shifted the emphasis in web cultures away from more static toward dynamic content and toward user engagement (we see for instance the importance of the comments made by visitors in response to posts on blogs).

2.3 Blogging has continued as a common practice in internet cultures, but over the last two to three years we have seen the emergence of other user-generated web applications. Indeed, these Web 2.0 applications have now become some of the most visited sites on the web with MySpace alone reportedly receiving 'more "hits" per day than the now ubiquitous Google' (Robinson, 2006: 20). Web 2.0 applications then have become an embedded and routine part of contemporary everyday life, particularly for young people (Lenhardt and Madden, 2005) but, even before sociologists have begun to get a handle on the phenomena, the processes of cultural speed-up (Gane, 2006) that we noted above have begun to come into play; it has recently been reported, for instance, that following the rapid rise of MySpace during 2006 it is now considered 'so last year' by its predominately 'teen' audience (Noguchi, 2006; Sessums, 2006).

2.4 To open up this definition of Web 2.0 a little further we can adopt a recursive strategy by turning (as do many of our students of course) to the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia, which is a paradigmatic instance of a collaboratively produced Web 2.0 application. Here, at the time of writing, Web 2.0 is described as:

'a phrase coined by O'Reilly Media in 2004 [to refer to] a supposed second generation of internet based services – such as social networking sites, wikis, communication tools, and folksonomies – that emphasize online collaboration and sharing among users. O'Reilly Media, in collaboration with Media Live International, used the phrase as a title for a series of conferences and since 2004 it has become a popular (though ill-defined and often criticized) buzzword among certain technical and marketing communities.' (Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2)

2.5 Wikipedia is perhaps the leading example of how this type of open and collaborative practice operates to create an online repository of ideas and knowledge formed into a dynamic document that changes from day-to-day. Here users are involved as producers and consumers of the information, both browsing for and adding content to the project (although, of course, some users merely browse without contribution).

2.6 A second key feature of Web 2.0 is the operation of software 'above the level of a single device' (O'Reilly, 2005). The point here is that in place of information storage on any single device Web 2.0 applications make information accessible through any web enabled interface. Here information moves from the private device out into the network allowing for it to be accessed from a range of mobile and desktop interfaces at anytime and from anywhere. This represents an instance where the 'technology itself – in terms of both applications and operating software – moves from the desktop to the webtop' (Lash, 2006: 580). For Lash this has created an 'age of the portal' where 'the data find you' (Lash, 2006: 580). This is highlighted as we are frequently confronted with recommendations, news specific to our interests or about our friends, suggested purchases and other things of supposed interest. These 'knowing' (Thrift, 2005) systems anticipate, through strategic data mining and classification, and search us out rather than the reverse.

2.7 The rise of Web 2.0 has been genealogically connected with the type of business that survived the 'bursting of the dot-com bubble in the fall of 2001' (O'Reilly, 2005); that is to say that it is sites with Web 2.0 characteristics - those closest to the participatory model - that are now flourishing (O'Reilly, 2005; Maness, 2006). Use of the term is also becoming ubiquitous. A search for 'Web 2.0' on Google, for example, retrieved 'about 124,000,000 results' at the time of writing, and entering it into the still experimental Google Trends (http://www.google.com/trends) revealed a significant escalation in recorded searches from mid-2005 onward (with by far the most searches originating in the USA and South East Asia).

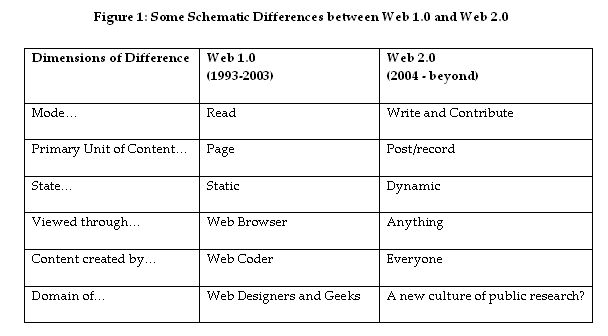

2.8 Understandably, ongoing debates continue over exactly what is meant by Web 2.0. As O'Reilly points out, there are those 'decrying it as a meaningless marketing buzzword, and others accepting it as the new conventional wisdom' (O'Reilly, 2005: 1). However, in lieu of a more descriptive and historical account of Web 2.0, the technical details of which this paper is not concerned, the basic features of Web 2.0 outlined can be schematised, as in Figure 1 (which is a slightly amended version of one originally developed by Michael Hardey of the Hull York Medical School, which itself was inspired by O'Reilly (2005)), and provides us with a useful sensitising conceptual mapping of our topic of inquiry.

2.9 To further develop this we will focus on four types of Web 2.0 application around which our discussion can be organised: wikis, folksonomies, mashups and, most significantly we sense, social networking sites (SNS).

|

Wikis

2.10 Wikis can be understood as user-generated resources constructed and edited by anyone who wishes to contribute, the most well-known example of which, as we have already discussed, is the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia. Other examples of wikis include http://www.encyclopedia.com, http://www.martindalecenter.com, and http://www.onelook.com. The pages generated on these Wikis are linked together by a network of live hyperlinks in the text that allow users to skip through to related pages. The term Wiki is an abbreviation of "Wiki Wiki" meaning "quick" in Hawaiian and has been in use for describing this phenomenon of open collaboration for around 10 years.

2.11 The first Wiki was created by Ward Cunningham, a software designer from Portland in Washington, who wanted to have a simple database system that would allow him to easily exchange design patterns with his international contacts and for the design team to work collaboratively from different geographical locations (Korica et al., 2006: 2). This type of 'software…enables every user to easily change the content of a page by clicking on an "Edit Page" button' (Korica et al., 2006: 2). It is this edit facility, open to anyone, that is the key feature of wikis. The second key feature is the 'sophisticated version control which enables users to see recent changes and the history of the changes of a Web page' (Korica et al., 2006: 2). This function allows users to make and track changes in the editing processes, correcting 'mistakes' and tracking additions that are 'inaccurate' or out of date.

2.12 In short, wikis can simply be described as 'open web-pages, where anyone registered with the wiki can publish to it, amend it, change it' (Maness, 2006: 6). This, of course, generates a range of questions about the reliability and authority of information. The open editing means that these sites are open to vandalism and subversive actions as well as questions about accuracy, sources of information, standards, and the possibility of mistakes.

2.13 An interesting sociological example of this can be found in the wikipedia entry on Harvey Sacks (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harvey_Sacks), who is often credited with founding conversation analysis. The neutrality of the entry is disputed and clicking through on the 'talk page' page and the 'history' tab reveals a quite amazing set of ongoing claims, counter-claims, edits and re-edits. Here we see that these collaborative ventures track the dialectics of thought on Sacks as users dispute the entries and interpretations of other users. The text of the Wiki then becomes a product of the tensions in the discipline and an outcome of disputed territory. Rather than the fixed authoritative accounts of the printed word, these are dynamic entries that tell us not only about the searched term but also about the turbulent underpinnings of 'collective intelligence' (O'Reilly, 2005). It will be interesting to see how sociology – and other disciplines of course – respond to this. A fascinating example will be to track how the ambitious Theory, Culture and Society New Encyclopaedia Project (http://www.sagepub.net/tcs/bin/main.aspx?page=encyclopedia) develops.

Folksonomies

2.14 One of the key practices behind Web 2.0 is tagging, this involves locating and marking or classifying a webpage with a metadata label. Tagging 'enables users to create subject headings for the object at hand…[and]…to add and change not only content (data), but content describing content (metadata)' (Maness, 2006: 8). Tags act as metadata operating behind web pages enabling them to be organised into classified networks. The result is that tagging makes 'lateral searching easier' (Maness, 2006: 8). We can move in non-linear directions from one page onto pages that have something in common, or, when finding similar pages tag them to enable other users to make the same connections.

2.15 Two of the most widely used folksonomies are del.icio.us.com and flickr.com. Del.icio.us enables users to keep their bookmarked pages together and to look through other users' bookmarks to create new sets of tagged links. So, for example, searching for sociology on Del.icio.us finds 18,500 bookmarked and tagged pages to browse through. Flickr is a photo repository that allows the user to store, search, sort and share pictures. Searching Flickr for the name of the college in which the authors wrote the majority of this article for instance finds a handful of photos of the building. Using the broader search terms of 'sociology lecture' 18 photos are found of sociology lectures including a link to a series of pictures of Zygmunt Bauman delivering a lecture at Växjö University in Sweden.

2.16 Finally, the most well known and highly used folksonomy is the online video repository http://www.youtube.com. YouTube now hosts over 100 million video downloads per day and it has even been suggested that this may offer a viable alternative to mainstream cinema or television (Bradshaw, 2006). By way of example, in March 2007 almost 500 videos had been tagged as 'sociology' – one, a 4-minute interview with Michael Mann, Professor of Sociology at UCLA (who we will meet again later on), was also tagged with 'Michel' (sic), 'Mann', 'social', 'power', ' world' and 'history'. The others included student's sociology projects or clips of students performing various 'stunts' in sociology classes. A notable example of a sociology video on Youtube is the paradoy of sociology at the University of Chicago which can be found at http://uk.youtube.com/watch?v=PohmxAOlN5Q&mode=related&search=

Mashups

2.17 Mashups are 'hybrid applications, where two or more technologies or services are conflated into a completely new, novel, service' (Maness, 2006: 9). The term has been appropriated from pop music where a DJ takes, for example, a vocal track from one song and combines it with the instrumental track of another to produce something new. Many Web 2.0 applications are, in fact, mashups of various sorts (Maness, 2006: 9). Mashups are used to create various applications, although they 'often (but not always) have a mapping component' (Lerner, 2006: 1). One infamous example not based on maps is Gizoogle ( http://www.gizoogle.com), which converts webpages into politically incorrect Snoop Dogg style discourse.

2.18 The point of mashups is that they present existing information in new ways. In the case of mashed-up maps, this enables patterns to emerge in the data. This means that as information about crime rates, for example, become mashed up with google maps, the user can see instantly groupings of crimes. Take for instance this account of an encounter with a mashup taken from the open source software focused Linux Journal:

'One of the first Mashups I saw was the Chicago crime map. The Chicago Police Department publishes a regular bulletin of crimes that have taken place within the city, and their approximate location…I was living in Chicago at the time it came out, and (of course) used the listing to find out just how safe my neighbourhood was. The information always had been available from the police department, but it was only in the context of a mapping application that I was really able to understand and internalize this data' (Lerner, 2006: 1).

2.19 A history and inventory of mashups are available at http://www.mashups.com and further discussion of some of the possible sociological implications of mapping mashups – especially for the possibility of the emergence of a new public culture of social research - can be found in Hardey and Burrows (2008).

Social Networking Sites

2.20 Social networking sites (SNS) are perhaps the most socially significant of the Web 2.0 applications, particularly as the number of users continues to escalate and as they converge a range of other Web 2.0 phenomena (see for example the map-mashup SNS site http://www.mymapspace.com). MySpace already has over 130 million members (a 'population' already over twice that of the UK) and Facebook around 18 million.

2.21 SNS users build profiles about themselves, posting photos, information about their backgrounds, views, work, and so on, and make 'friends' with other users. These networks often enmesh virtual and physical friendship groups as they 'support both distant and geographically proximate relationships' (Golder, et al., n.d.). For example, SNS are often used by people who know each other from colleges or work places to organise physical meetings, to discuss things that happened that day, to set up events and so on. Also users make new connections in the virtual that then later become real-world connections. This creates an interesting convergence of virtual and physical worlds. Connections and friendships now stretch out across physical and virtual spaces as users communicate with 'real-world' friends through SNS and other Web 2.0 applications (Wellman, 2001). University students on the same courses at the same university, for instance, use SNS to discuss their work, lectures and their lecturers (as we shall see below), arrange social events, and share pictures of get-togethers.

2.22 Already if we search the groups formed on the SNS Facebook (http://www.facebook.com) we find numerous collectives have been formed to discuss sociology and related matters, these include names such as 'Sociology Society', 'Sociology – we like men with beards', and 'The Sociology and Social Policy Elite'. These various groups host sociology students from universities all over the world. Indeed, many sociology students, particularly undergraduates are members of Facebook. The institution at which the authors were based at the time of writing, which has nearly 10,000 students in its network, currently has 268 student profiles connected with sociology (a significant majority of all sociology students)

2.23 The cultural impact of the new SNS has been significant in another way as well, connected as it is to the rise of particular artists and to a new series of connections between popular music performers and their audience (Beer, 2006). Indeed, it is now the case that 'more than 240,000 artists…are using MySpace as a way to market themselves and build a fanbase' (Cohn, 2005). It is common, almost compulsory, for popular music performers and bands to have profiles on SNS through which they can communicate with their fans (or so we are led to believe). In fact it is now unusual for bands not to have some form of presence. Cohn claims that the change here is that:

'For fans, MySpace allows them to keep up-to-date on bands in an intimate way. Fans…can leave comments on a band's site…and band members often respond to fans, creating a real dialogue between artists and their followers.' (Cohn, 2005)

2.24 Again the suggestion is that a new series of connections and a 'democratisation' of the musical landscape is emerging as established artists communicate with their public, and where new and unsigned bands can distribute their music, create a fanbase and become popular without the backing of the corporate music industry.

Sociology of Web 2.0

3.1 There seems to us to be at least three interrelated issues that the Web 2.0 phenomena invokes that require sociological engagement: the changing relations between the production and consumption of content; the mainstreaming of private information posted to the public domain; and, our main focus here, the emergence of a new rhetoric of 'democratisation'. This is not to say that these are entirely new areas of interest for investigation or that these issues have emerged solely out of Web 2.0 applications, rather what we are pointing toward here are issues that it seems to us are particularly pressing if we wish to move toward sociological accounts of Web 2.0. As these developing online technologies remediate that which went before, so too we find theoretical remediations are required as we rethink familiar sociological issues in light of Web 2.0.The changing relations between the production and consumption of content

3.2 In a recent report on libraries and Web 2.0, Maness concluded that 'the line between the creation and consumption of content in these environments was blurred' (Maness, 2006). Indeed, the blurring of production and consumption has become a common theme in the literature on the digitization of culture (Taylor, 2001; Théberge, 1997). Perhaps the key-defining feature of Web 2.0 is that users are involved in processes of production and consumption as they generate and browse online content, as they tag and blog, post and share. This has seen the 'consumer' taking an increasingly active role in the 'production' of commodities (Thrift, 2005). Indeed, it is the mundane personal details posted on profiles, and the connections made with online 'friends', that become the commodities of Web 2.0. It is the profile, the informational archive of individuals' everyday lives, that draws people into the network and which encourages individuals to make 'friends'. In the case of http://www.xuqa.com the popularity of those in the network even takes centre stage in the form of online popularity contests where, the site informs us, users 'socialize and compete to become the richest and most popular person in the game'. In the case of wiki's and folksonomies it is the construction of collaborative projects – as collections of photos or videos and the literature that comes out of communal contribution – that may be understood as the commodity. Although it remains unclear what the motivations for participating in such collaborative ventures are, it is certainly clear that there are millions of (what we might call) 'wikizens' making active contributions to the shaping of content and the virtual spaces through which they navigate.

3.3 The pressing questions here relate to the 'cultural circuits of capital' (Thrift, 2005) that underpin Web 2.0. First, it is important to note that although these networks are free-to-access and user-generated they remain overwhelmingly commercial. Second, it is the user profile that has become the commodity of Web 2.0, as users engage in simultaneous acts of production and consumption. This is not just the profiles of cultural luminaries, but also of the 'ordinary' user. Even making connections in the network is an act of production as it generates a path with its own history. This is illustrated most clearly by the SNS Facebook, which provides news about what your 'friends' have been up to every time you log-on (this includes the people they have made 'friends' with, the groups they have joined, and the changes they have made to their profiles). We return here to Lash's (2006) emphasis upon the importance of 'the feed' and the image of the data actively 'finding' us. The movement toward the user-generated profile as commodity, and even the collaborative accumulation of repositories of the wiki, folksonomy and mashup, may be understood in broader terms as a part of the 'changes in the form of the commodity [that] point to the increasingly active role that the consumer is often expected to take.' (Thrift, 2005: 7). Understanding these commodities requires analytic attention to be focused on the transformation in the nature of the relations between production and consumption as they become simultaneous and even ambient in the routine activities that generate the content of Web 2.0.

The mainstreaming of private information posted to the public domain

3.4 The act of production, particularly in the case of SNS, creates a situation in which private information becomes open and accessible to anyone with access to the Internet. Thoughts, views, education/employment information, personal photographs and so on become accessible as private information is posted to the public domain. Indeed, one might think about this as another manifestation of a more general process associated with the new technologies that seems to necessitate the ever more detailed codification of habitus (Burrows and Gane, 2006). This, in itself, is an interesting shift in the values of privacy that people attach to such information, as wikizens are willing to detail some of the most private information about themselves where anyone can access it, and this, of course, also raises a number of pressing questions about surveillance. Who is accessing this information? What are they using it for? Already it has been reported that the Pentagon's National Security Agency is funding research into the 'mass harvesting of information' posted on social networking sites (Marks, 2006).

3.5 A recent study of MIT students disclosure of information and the protection of this information on Facebook found that 'Facebook was firmly entrenched in college student's lives, but users had not restricted who had access to this portion of their life' (Jones and Soltern, 2005: 4). In addition to this the researchers found that 'third parties were actively seeking out information' (Jones and Soltern, 2005: 4). In this instance the researchers concluded that in light of the threat to privacy it will come down to the 'common sense' of users to moderate the disclosure of their own information as they become aware of the consequences. However, it would seem that these notions of 'common sense' will more than likely have shifted along with changes in understandings and values attached to privacy. In other words we see little attempt here to conceal information. Rather the emphasis appears to be about revealing as much information as possible in line with the projected image that the user wishes to cultivate.

3.6 The more general point here though is that as users participate in generating or producing content they build up an archive of their 'everyday life' that is openly accessible. As we have noted, this type of information about preferences, choices, and other personal details are considered valuable in an age of 'knowing capitalism' where data-mining and predictive technologies are prominent. But the self-production of such data also allows for the emergence of a new more general culture of 'sort' to be facilitated. It is not just places (Burrows and Ellison, 2004) or those looking for 'love' (Suna et al., 2006) that are now being 'sorted' and/or 'matched' – something far more generic is happening. The browsing function on MySpace is interesting here. Selecting the 'advanced' option for browsing generates a form that enables profiles to be found that fit certain criteria. Profiles can be located by entering responses to a range of criteria including: gender; age; relationship status; what they are looking to get out the network; geographical location (including distance from a particular postcode); ethnicity; body-type; height; sexual orientation; education; religion; income; number of children; and so on. Browsing these criteria generates a list of profiles that fit and that may be ordered in relation to proximity to the stated location or some other criteria. Similarly on Facebook, we may click on a preference, a favourite film or musician for instance, and a list of members of the network who share that preference is generated. These then form vast expanses of data about people that can be sorted and accessed.

A new rhetoric of 'democratisation'

3.7 Finally, Web 2.0 has been ushered in by what might be a thought of as rhetoric of 'democratisation'. This is defined by stories and images of 'the people' reclaiming the Internet and taking control of its content; a kind of 'people's internet' or less positivley, the emergence of the cult of the amataur (Keen, 2007). This, we are led to believe, has led to a new collaborative, participatory or open culture, where anyone can get involved, and everyone has the potential to be seen or heard. According to this vision there are opportunities for our thoughts to get heard, our videos to be seen, and our music to be listened to. This rhetoric demands detailed and critical interrogation to reveal: how it is formed; the formation of new hierarchies and social divisions; the power of the new culture industries; the problems and subversions afforded by the collaborative culture; patterns of social participation; the creation of new 'in-crowds'; the operations of new viral marketing strategies; and, who it is that gets heard above the din that is Web 2.0. As we have noted, despite the rhetoric of 'democratisation' Web 2.0 is a commercial and lightly regulated market. It is then also a space where a virulent form of consumerism can easily undermine 'democratic ideals'. Many service providers who are already subject to comment on sites such as http://www.tripadvisor.co.ukor the reviews and feedback sections of retail sites such as http://www.amazon.co.uk, know about the implications of this. Colleagues in academia have, hitherto, not been subject to such processes. However, it is on the way.

3.8 Consider, by way of example, Facebook in the UK. As we noted above (at the time of writing) at our own institution nearly 10,000 students are registered with this popular SNS. Over one-half of those registered check their profiles at least once a day. Not surprisingly, some of the discussion is about academic staff. As part of Facebook one is able to form various groups; so we have a Sociology Society for example that has 150 members, an Urbaphilia group for staff and students interested in urban studies, a feminist conversation analysis group and so on. Students also form groups dedicated to the dis/appreciation of various staff members (none from Sociology as it turns out) – often with overtones of sarcasm and in-jokes that are not always easy to decipher. So, one group describes its function as follows:

This group is for the many who have fallen asleep or skipped X's lectures, and also for the few that endured great boredom by actually attending them.Another as a:

Group dedicated to the University's worst lecturer…If you have ever had the displeasure of sitting through one of her lectures you will know the burning desire to end your life because she is that bad.Example postings include the suggestion that:

We should get a petition going against the worst lecturers teaching us the hardest modules! Or just send the department the link to this page.

3.9 Other postings are openly sexist and offensive. One member of staff about to go on maternity leave is subject to a discussion that includes the comment:

Hold on, pregnant AGAIN? Is this the same pregnancy as was at the end of last year or a whole new one? If the latter, she certainly doesn't waste time, does she?

3.10 Also, in a separate incident a Facebook group was set up with the express intention of complaining about a particular exam paper. The group accumulated over 170 members and was used as the hub for coordinating the student complaints. This included the posting of a letter that could be cut and pasted with email links for where to send it.

3.11 The press has picked up on some of the implications of these Web 2.0 technologies for higher education after students posted mobile phone video material of lecturers on YouTube without their knowledge or permission (Baty & Bins, 2007). One unfortunate academic filmed scratching his crotch during a lecture had to endure the clip being downloaded from the site over 8000 times. But the implications go far further than being merely scandalous as we face up to what are effectively dehumanised accounts of lecturers. What are the implications for the health and welfare of staff on the receiving end of such public criticism? Imagine the anguish of discovering a Facebook group dedicated to ridiculing you, where your perceived inadequacies and even personal issues are being discussed by students in an open forum. And what of the students who open up their private life and thoughts to a public audience? The posts made are automatically connected to the user and their profile so can easily be tracked back. Who is watching? The university? Future employers? Is this empowering anyone? Are formal systems of measurement and feedback being bypassed by these informal postings and ratings? Are staff and students more accountable? These are significant questions that lead into even larger ones concerning the future of surveillance, trust and privacy in a Web 2.0 enabled consumer society. We also see here links to issues encountered in other sectors, and particularly the health sector, with regard to the consequences of the availability of this type of information for working practices and self-identity. There are new and forthcoming emotional challenges here facing those working in academia and across a range of areas.

3.12 These largely unsystematic evaluations of the work of academics on UK SNS pale into insignificance in comparison with what is already quite mundane in a North American context. Other Web 2.0 sites, themselves often linked to SNS, offer open access comment on all staff in all institutions of higher learning by students. For example http://www.ratemyprofessors.com advertised as 'where students do the grading' contains more than 6,750,000 separate ratings of over 1 million academic staff working in over 6000 institutions in the USA and Canada. The site also has provision for comments about staff in the UK but (so far) there has been little traffic.

3.13 On these sites students can not only grade staff using quantitative scales (rather like most systems of formal course evaluations) they can also rate the sexual attractiveness of the member of staff (by allocating a number of red hot chilli peppers as a measure of their 'hotness'). However, it is the free-form comments that must be of most concern to readers. Examining the entries of a well-respected Department of Sociology we find one member of staff who has been rated by almost 40 students. He is apparently very highly regarded as he is rated very highly on all of the scales and, in addition, is considered to be rated 'hot' in terms of attractiveness. His qualitative evaluations are glowing:

Simply the best Prof I have ever had!!! He is smart, has a sense of humour, and he just brilliant! If you are going to take theory, take it with Dr X. you will not regret it, and there cannot be a better Prof to teach your weber, marx and durkheim!!!

The best lecturer ever. I never thought theory could be so interesting. He's hilarious and brilliant. He can make any topic interesting. Marking and tests are fair. Would love to take more classes with him.

3.14 However, not all staff are so well respected. One staff member rated very poorly on all scales (resulting in a blue coloured 'smiley' face looking very upset) is subjected to what can only be described as abuse:

I hate him so much. He missed 4 classes, and when he did show up, I was elsewhere quietly protesting. Should read more contemporary urban theory and get out of the 1970s.

He is an unorganized, pompous, inconsiderate and lazy teacher. I wish I had never wasted time and money on his class.

3.15 Another example, explicitly linked to Facebook in the USA, is a mashup called http://www.pickaprof.com, which presents information on over 98,750,000 grade histories, almost 11.5 million ratings and reviews on over 880,000 Professors by 580,000 Facebook 'friends'. So, if we look at Michael Mann at UCLA again – probably one of the most prestigious and pre-eminent British sociologists of his generation - who we have already met in a video downloaded from YouTube we can see that of the 14 students who took one of his modules 53 per cent obtained 'A' grades and 47 per cent got a 'B' - a GPA of 3.57.

Sociology in Web 2.0?

4.1 Before entering into a discussion of the things we have highlighted above it is necessary first to clarify our position. When we talk, for instance, of a rhetoric of democratisation we are not talking of Web 2.0 as a democratising force. We are instead pointing to the way in which Web 2.0 is being constructed or, as we say here, ushered in by particular discursive frameworks. It is not really our place at this juncture to say if Web 2.0 is empowering or democratising, it is too early; conversely we do not wish to cultivate a moral panic over the consequences of these things. We are also happy to accept that 'Web 2.0' may have already become a 'zombie category' (Beck, 2004). As such the benefit of using Web 2.0 terminology is open to debate. Maybe it is here that sociology could begin to make a contribution?4.2 In this paper we have briefly highlighted a range of 'flickering connectivities' (Hayles, 2005), or, in the case of SNS, flickering friendships. Understanding these connectivities, their motivations, how they come about, the hierarchies and divisions, and even who it is that populate and contribute to these applications is a problem with which we are now faced if we wish to form sociological understandings of Web 2.0. As we indicated at the outset of this paper, it is our sense that by the time this paper is published this type of user-generated application - whether we continue to refer to it as Web 2.0 or some other such term - will have become part of the cultural mainstream. There is a possibility that the technologies we have described are contributing to a major remediation of television, radio, music, writing, art, possibly academia, and even the processes of meeting people and making 'friends'. It is the place and responsibility of sociology to react. The question then, even if we wish to delve further into a range of sociological issues to append the brief list we have summarised above, is how?

4.3 One possibility is that future research will have to 'come from inside the information itself' (Lash, 2002: vii). There are two issues here. First, we need to be inside of the networks, online communities, and collaborative movements to be able to see what is going on and describe it. If we take Facebook for instance, it is not possible to enter into and observe the network without becoming a member, providing an institutional email, entering some personal details and generating a profile. Therefore, in order to get some idea of users and their practices it is necessary to become a 'wikizen'. The social researcher will need to be immersed, they will need to be participatory, and they will need to 'get inside' and make some 'friends'. We will have to become part of the collaborative cultures of Web 2.0, we will need to build our own profiles, make some flickering friendships, expose our own choices, preferences and views, and make ethical decisions about what we reveal and the information we filter out of these communities and into our findings. Our ability to carry out virtual ethnographies will – by necessity – involve moving from the role of observer to that of participant observer.

4.4 A second issue is that once inside these networks we may explore the possibilities of using Web 2.0 applications, and particularly the interactive potentials of SNS, as research tools or research technologies (this is not necessarily limited to research into Web 2.0, SNS could be used to conduct research on any topic). Interviews and even focus groups could comfortably be conducted through SNS, either privately or in the open. Of course, there are a range of alternatives here. We can imagine the construction of virtual ethnographies accounting for these communities of users and their practices. Perhaps, more significantly, what we have, particularly with SNS, are vast archives on the everyday lives of individuals - a sort of ongoing codification of habitus - their preferences, choices, views, gender, physical attributes, geographical location, background, employment and educational history, photographs of them in different places, with different people and different things. These are open and accessible archives of (what was once thought of as sensitive) information that may be used to develop understandings of these people and to track out communities or networks of friends. These archives could be used to track preferences, connections, personal histories, views, friendships that may be data-mined, mapped, network analysed, discourse analysed and so on. There are possibilities then for tailoring innovative research strategies that take advantage of the interactive potentials of these new media and of the data that they hold. But can we, should we, use it to study itself?

4.5 As sociologists what we may need to do is take a leaf out of the 'wikizens' book and adapt to the possibilities of research from within the information flows. Mimicking, in a sense, the desire of wikizens to find out about each other and the connections people make by browsing through SNS. 'Wikizens' are already engaged in sociological research of sorts (Hardey and Burrows, 2008). SNS in particular reveal a sociological tendency in web users as they search and browse through profiles of their fellow 'wikizens', reading about them, looking at photographs and so on. This engagement in a vernacular sociology – an ongoing interest in the mundane lives of other people – could be read as a potentially positive thing (as people are seen to take an interest in one another). However, we are not really sure, apart from the practices intimated by our cursory investigations, how people use these networks or for what outcome. It would seem that we have seen a radical shift in senses and values of privacy, where people are prepared to expose details about themselves without concern, the formation of web cultures that are about getting noticed, accumulating 'friends', posting videos and music that gets circulated, and all of the rest. We may, for instance, begin to place Web 2.0 into broader contexts of celebrity culture – the celebration of the mundane, reality TV, celebrity reality TV, gossip magazines, and the 'voting out' cultures of X-factor and any other number of programmes. It is certain that one significant difference between the citizen and the 'wikizen' is the value that they place on privacy.

4.6 In terms of conceptualising this change it would seem that Urry's (2003) recent call for new concepts that better capture the contemporary complexity turn is entirely fitting. There are clearly possibilities for generating new concepts or for reinvigorating old concepts in light of what is happening. On the later we can imagine reworkings of the concept of the flâneur for instance. Here we can visualise the 'wikizen' as flâneur, wandering without direction around wikis, folksonomies, mashups and SNS, taking in the surroundings without concern for a final destination. Indeed, recently the flâneur has been re-energised as a concept for understanding the experiences of virtual space – the 'virtual flâneur' (Featherstone, 1998), the 'cyborg' flâneur (Shields, 2006), and the 'flâneur electronique' (Atkinson & Willis, 2007). The problem is that unlike the flâneur wandering around the Paris arcades as described in Benjamin's 1930s Arcades Project (1999), or even the more recent reworkings of the flâneur wandering around virtual space, the wikizen is instead involved in generating and shaping the environments that they wander through and observe. The point here is that in light of Web 2.0 it is necessary to reconsider how we conceptualise what is happening. The first step may well be to construct more complete and differentiated descriptions of what is happening in Web 2.0, who is involved, and the practices entailed, in order to inform and enrich new concepts or reworkings of our theoretical staples. It is here that a movement toward a more descriptive sociology may fit.

4.7 As a final note, once we have entered into these Web 2.0 applications it may also be worth giving some thought as to how they may be used to teach sociology. We can imagine here students building their own sociologically motivated mashups, collaborating to put together wiki's on sociological topics, running seminars online through SNS, continuing to use SNS groups and profiles to informally discuss sociology or using folksonomies to tag and collate sociology content online (allowing students to create their own reading lists, or perhaps even using SNS as archived data sources on which to draw for short term research projects and dissertations). Of course, this may already be happening.

4.8 We set out from the premise that what is needed is a renewed interest in sociological description. Admittedly we have not been able to offer the depth of description here that we would have liked – although one of the many benefits of publishing this article in Sociological Research Online is that the reader can click on links to investigate the examples further. We would emphasise that this piece is really only a cursory introduction and represents only some early thoughts on a topic that now requires sustained attention from sociologists in the round, and not just those with substantive interests in new media. At the moment it is hard to locate areas that go untouched by the implications of user-generated and openly accessible content – and these implications are sure to spread out across social and cultural spheres over the coming months and years. As we have pointed out here, it even has a range of implications for us as sociologists. Not only does it create for us new opportunities for research, and maybe teaching, but these applications are already being used to say things about us, about the concepts and writers that we use, about our teaching, and about our institutions. Whatever we may choose to call it, it is important that we at least acknowledge that we are being subject to processes of remediation, and to begin to think through how we might respond.

References

ATKINSON, R. & Willis, P. (2007) 'Charting the Ludodrome: The mediation of urban and simulated space and the rise of the flâneur electronique' Information, Communication & Society vol. 11, no. 6, forthcoming.

BAUDRILLARD, J. (2001) Impossible Exchange, Verso, London.

BAUDRILLARD, J. (2002) The Spirit of Terrorism, Verso, London.

BATY, P. & Binns, A. (2007) 'Lecturers pilloried online', The Times Higher Education Supplement, 2 March, p.1 and pp.8-9.

BECK, U. (2002) 'The Cosmopolitan Society and its Enemies', Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 19, no. 1-2, pp. 17-44.

BEER, D. (2006) 'The Pop-Pickers Have Picked Decentralised Media: The Fall of Top of the Pops and the Rise of the Second Media Age', Sociological Research Online, vol. 11, no. 3, <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/11/3/beer.html>

BENJAMIN, W. (1999) The Arcades Project. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

BRADSHAW, P. (2006) 'And now for some snuff comedy…', The Guardian, G2, 24 October, pp.28-29.

BURROWS, R. and Ellison, N. (2004) 'Sorting Places Out? Towards a Social Politics of Neighbourhood Informatisation' Information, Communication and Society, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 321-336.

BURROWS, R. and Gane, N. (2006) 'Geodemographics, Software and Class' Sociology, vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 793-812.

COHN, D. (2005) 'Bands Embrace Social Networking', Wired News, 18 May, <http://www.wired.com/news/culture/1,67545-0.html>(7 December 2006).

FEATHERSTONE, M. (1998) 'The Flâneur, the City and Virtual Public Life' Urban Studies, vol. 35, no. 5-6, pp. 909-925.

GANE, N. (2006) 'Speed Up or Slow Down? Social theory in the information age' Information, Communication & Society, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 20-38.

GOLDER, S., Wilkinson, D. & Huberman, B. (n.d.) 'Rhythms of social interaction: messaging within a massive online network', Cornell University Library, <http://arxiv.org/abs/cs.CY/0611137>(15 March 2007).

HARDEY, M. and Burrows, R. (2008) 'Cartographies of Knowing Capitalism and the Changing Jurisdiction of Empirical Sociology' in N. Fielding, R.M. Lee and G. Blank (eds) Handbook of Internet and Online Research Methods London: Sage.

HAYLES, N.K. (2005) My Mother Was A Computer: Digital Subjects and Literary Texts. Chicago and London: The Chicago University Press.

JENKINS, H., Clinton, K., Purushotma, R., Robinson, A. J., & Weigel, M. (2006). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century. MacArthur Foundation. Available at <http://www.digitallearning.macfound.org/>

JONES, H. and Soltren, J.H. (2005) 'Facebook: Threats to Privacy', Project MAC: MIT Project on Mathematics and Computing, http://www-swiss.ai.mit.edu/6.805/student-papers/fall05-papers/facebook.pdf (16 March 2007).

KEEN, A. (2007) The Cult of the Amateur: How Today's Internet is Killing Our Culture. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

KORICA, P., Maurer, H., and Schinagl, W. (2006) 'The Growing Importance of e-Communities on the Web', Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference on Web Based Communities, San Sebasitan, Spain.

LASH, S. (2002) Critique of Information. London: Sage.

LASH, S. (2006) 'Dialectic of Information? A response to Taylor' Information, Communication & Society, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 572-581.

LASH, S. & Lury, C. (2007) Global Culture Industry: The Mediation of Things. Cambridge: Polity.

LATOUR, B., (2005) Reassembling the Social, Oxford, Clarendon,

LENHART, A. & Madden, M. (2005). 'Teen Content Creators and Consumers', Pew Internet & Amercian Life Project, <http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Teens_Content_Creation.pdf>(12 December 2006)

LERNER, R.M. (2006) 'At the Forge: Creating Mashups', Linux Journal, Issue 47, July.

LUNENFELD, P. (2000) Snap to Grid, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

MANESS, J.M. (2006) 'Library 2.0 Theory: Web 2.0 and its implications for Libraries', Webology, vol. 3, no. 2, <http://www.webology.ir/2006/v3n2/a25.html>

MARKS, P. (2006) 'Pentagon sets sights on social networking websites', NewScientist.com, 9 June, <http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=mg19025556.200&print=ture>(7 December 2006).

MCLUHAN, M. (1997) Marshall McLuhan Essays: Media Research, Technology, Art,

Communication, ed. M. A. Moos, G & B Arts International, Amsterdam

NOGUCHI, Y. (2006) 'In Teens' Web World, MySpace Is So Last Year', Washington Post, October 29, <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/10/28/AR2006102800803_pf.html> (12 December 2006).

O'REILLY, T. (2005) 'What is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software', O'Reilly, <http://oreillynet.com/1pt/a/6228> (7 December 2006).

PICKSTONE, J., (2000) Ways of Knowing. Manchester, Manchester University Press.

ROBINSON, J. (2006) 'Mister Space Man', Observer Music Monthly, December 2006, p.20.

SAVAGE, M. and Burrows, R. (2007) 'The Coming Crisis of Empirical Sociology', Sociology, vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 885-899.

SESSUMS, C.D. (2006) 'Teenagers and social networking: "MySpace is so Last Year"', 29 October, <http://elgg.net/csessums/weblog/136334.html>(7 December 2006).

SHIELDS, R. (2006) 'Flânerie for Cyborgs' Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 23, no. 7-8, pp. 209-220.

SUNA, T., Hardey, M., Huhtinen, J., Hiltunen, Y., Kaski, K. Heikkonen, J. and Ala-Korpela, M. (2006) 'Self-Organising Map Approach to Individual Profiles: Age, Sex and Culture in Internet Dating' Sociological Research Online, vol. 11, no. 1, <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/11/1/suna.html>

TAYLOR, T.D. (2001) Strange Sounds: Music, Technology & Culture. New York & London: Routledge.

THÉBERGE, P. (1997) Any Sound Your Can Imagine: Making music/consuming technology. Hanover & London: Wesleyan University Press.

THRIFT, N. (2005) Knowing Capitalism, London, Sage

URRY, (2003) Global Complexity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

WELLMAN, B. (2001) Physical place and cyberplace: The rise of personalizised networking. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 227-252.

WELLMAN, B. and Haythornthwaite, C. (eds) (2002) The Internet in Everyday Life Oxford: Blackwell.

VIRILIO, P. (1986) Speed and Politics, Semiotext(e), New York.

VIRILIO, P. (2000) The Information Bomb, Verso, London.