Public Intimacy in Neighbour Relationships and Complaints

by Elizabeth Stokoe

Loughborough University

Sociological Research Online, Volume 11, Issue 3,

<http://www.socresonline.org.uk/11/3/stokoe.html>.

Received: 26 Dec 2005 Accepted: 7 Jun 2006 Published: 30 Sep 2006

Abstract

This paper examines neighbour relationships as an example of non-familial intimacy. It focuses on the way disputes between neighbours often hinge on notions of obtrusive public intimacy, in which the sights and sounds of normatively private domestic lives become sources of complaint. The analyses are based on approximately 150 hours of naturally-occurring interaction with neighbours including telephone calls to mediation centres, environmental health departments and anti-social behaviour units, neighbour mediation interviews, police-suspect interrogations in neighbour crime, and neighbour issues broadcast on television and radio. It was found that while the neighbours maintain good relations at the edges of private spaces, the physical arrangements of domestic properties, with their shared boundaries, means that personal information can be transmitted and observed as a routine matter of course. Disputes often have their basis in the illegitimate breach of boundaries, and in the unwanted and unavoidable receipt of the sights and sounds of other people's intimate lives.

Keywords: Neighbour Relationships, Intimacy, Complaints, Disputes, Ethnomethodology

Introduction

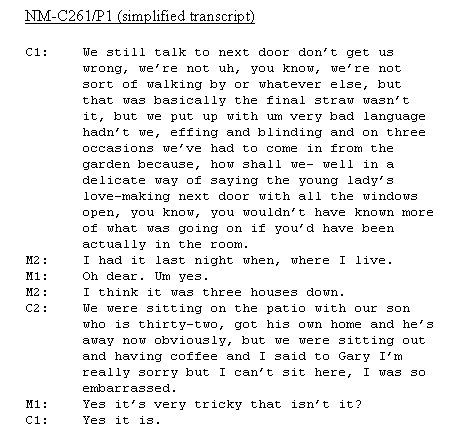

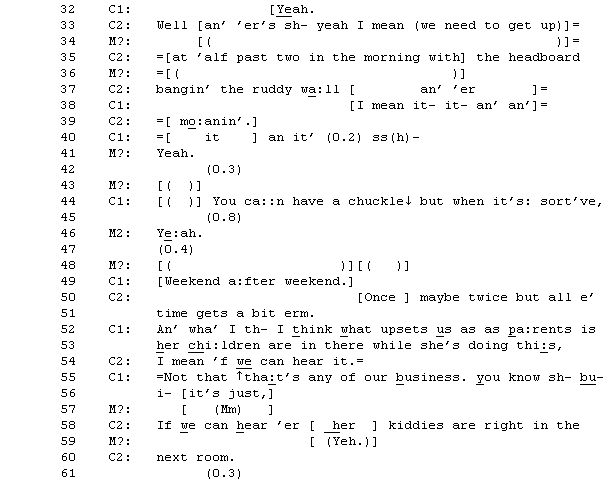

There is normally one position in your house from which you can see your neighbours doing things in their house. This can be the source of illicit pleasure until you realize that there's also the very same position in their house from which they can see what you're doing in your house. Go and borrow a cup of sugar and check it out for yourself (How to … have neighbours, Guy Browning, 2004).1.1 The topic of this paper is a relationship context that is particularly interesting with regards to non-familial intimacy: the neighbour relationship. More specifically, it focuses on the way disputes between neighbours often hinge on notions of obtrusive or public intimacy, in which the sights and sounds of normatively private domestic lives become sources of complaint. Let us start with a data extract to illustrate the paper's topic. It comes from a neighbourhood 'mediation' session, in which two mediators (M1 and M2) are interviewing two clients (C1 and C2), who comprise one party in a neighbour dispute. The eventual aim of mediation is to resolve disputes, by getting both parties to talk through their problems in the presence of a neutral mediator. The clients are complaining about their next-door neighbour's noise:

|

1.2 The "final straw" in the clients' complaint is the sounds of their neighbour's "lovemaking". A basic point about this sequence is that it is the proximity of their adjoining houses that provides the physical situation for the clients to hear intimate moments from their neighbour's life. However, their neighbour's "lovemaking" is overhearable not just because of this proximity, but also because she has left her windows open. The clients' account is one of passive overhearing – they are not being nosy – they cannot help but hear these sounds. Indeed, the sounds are so loud, and so specific, that "you wouldn't have known more of what was going on if you'd have actually been in the room". The clients' reported reaction is one of "embarrassment", such that they remove themselves from the location from where they can hear.

1.3 Whilst M1's response to the story ("Oh dear") treats it as a complaint, other types of responses to obtrusive, third-party intimacy are possible. What counts as a complainable matter is, therefore, something that speakers have to 'work up', given that any sound or activity can be understood in myriad ways. Other responses to stories about hearing one's neighbours having sex might include (1) vicarious interest or pleasure, (2) moral indignation and disapproval, or (3) an 'ethnographic' or informational interest (i.e. because intimacy is standardly private, we do not get to know how other people engage in sexual activities) (see Gurney, 2000). And, of course, people may try to bring off (1) as (3)! In our example, the clients' complaint, their reported reaction, and the mediators' responses tell us what counts, in our culture, as a transgression of normative neighbour relationships. The sounds of lovemaking should be contained within the boundaries of private space, they should not be overhearable, windows should be closed to contain them, and people should care about whether or not they can be heard doing intimate things.

1.4 The physical proximity of most dwellings means that people can get to know a lot about their neighbours, even though they might not know their names (note that C1 refers to "next door") or even recognize their faces (Laurier, Whyte & Buckner, 2002). They get to know their neighbours' daily routines, when they are on holiday, what kind of domestic arrangements they have, whether they have children, and what they own (cars, pets, plants, a powerful stereo, musical instruments, etc.). Neighbours can hear (and overhear) arguments, toilet flushes, children playing, music and television choices, sexual intercourse; they can smell next-door's dinner, painting, and pets; and they can see who comes and goes and at what time, who lives in the house, the type of house it is and its state of repair and choice of décor, and so on. And, as we will discover in this paper, people can build character-implicative assessments and judgements about their neighbours on the basis of this information. Neighbour relationships therefore need careful management with regard to the transmission of normatively personal, private activities from one dwelling to another. Homes are built to construct a particular kind of space, with boundaries (fences, doors, walls) within which people can live a private life. In our culture, "privacy" is a valuable commodity: a selling point for estate agents who, for example, emphasize that gardens are "not overlooked". However, the fact that most dwellings have shared boundaries (either adjoining interior walls, windows to see in and out of, or exterior fences) means that the private relationships of people and their neighbours can be somewhat transmitted to people who are not in that relationship. As Raban (1974: 6) notes, houses transmit "unasked-for intimacies, private sights, private sounds".

1.5 This current analysis of neighbour disputes contributes to broader fields of study. First, it adds to research in community and environmental psychology, sociology, and cultural geography, on topics pertaining to people's experiences of, and attitudes towards, various aspects of their neighbourhoods and communities. This work is generally conducted via large-scale surveys, questionnaires and/or interviews, designed to gather information about, for example, residents' reactions to changes in their neighbourhood and causes of pleasure, stress or conflict (e.g. Bonaiuto, Bonnes & Constinsio, 2004; Lee & Campbell, 1997; Vallance, Perkins & Moore, 2005). In some studies, factors such as 'environmental satisfaction', 'sense of community', and 'place attachment' are used in correlational studies to predict, for example, levels of physical and psychological well-being (e.g. Chuang, Cubbin, Ahn & Winkleby, 2005; Prezza, Amici, Roberti & Tedeschi, 2001). Measurable variables that increase people's 'sense of community' include high 'degrees of neighbouring' or 'levels of neighbouring activity' (e.g. Unger & Wandersman, 1983). The actual practices involved in 'neighbouring' are not always made explicit, although some authors list Likert-type items on their questionnaires to which subjects can respond (e.g. Skjaeveland & Garling, 1997; for a review, see Bridge, Forrest & Holland, 2004).

1.6 Second, a small number of studies focus particularly on 'noise' as a source of dispute between neighbours (van Dongen, 2001; Grimwood & Ling, 2001). Again, such studies generally rely on large-scale, self-report questionnaire methods to isolate the causes and subjective effects of neighbour noise, aiming to identify which categories of noise cause problems, for which individual type of person, and in what type of dwelling. Reported physical and psychological effects of neighbour noise include hearing loss, stress, sleep disruption, cognitive deficits and poor physical and mental well-being (e.g. Bronzaft, 2002). Stokoe and Hepburn (2005) observe that in much of this work, noise is treated (explicitly or implicitly) as a physical thing, with a straightforward meaning, that can be measured scientifically in terms of wavelengths, frequency, decibels, and the like. However, they show how 'noise' is a locally, contingently constructed phenomenon that cannot be separated from its social production and interpretation. The current paper further develops such an understanding of 'noise' as a situated phenomenon, accounts and descriptions of which cannot be separated from the interactional context in which they are produced. Relevant to this is Gurney's (2000) interview-based study of the social construction of 'coital noise', in which he examines people's accounts of and responses to hearing their neighbours' sexual activities. Gurney's work is an example of a larger body of new constructionist work in psychology, geography and sociology, which examines the discourse of place, space, exclusion, nationhood and boundaries (e.g. Cresswell, 1996; Dixon & Durrheim, 2000; Gunn, 2001).

1.7 Third, the paper updates and adds detail to the classic British and American ('Chicago School') micro-sociological and ethnographic accounts of communities and neighbourhoods and their social problems, as well as more recent sociological accounts of, say, the rise and decline of the concept of 'community', and the role of social class, age, gender and ethnicity in community and neighbour relations (Gans, 1962; Park, Burgess & McKenzie, 1925; Willmott, 1963; see also Crow & Allan, 1994; Galster, 2001; Warr, 2005). For example, in his study of a New York housing complex, McGahan (1972) interviewed residents about their role as neighbours. He devised measures of neighbouring that assessed 'extensiveness' (the range of neighbour relationships a person had) and 'expressiveness' (the level of intimacy in those relationships). From the participants' responses, McGahan defined the 'good' neighbour as someone who is "friendly, but not a friend', 'willing to chat, but … does not intrude on your privacy" (p. 402).

1.8 A more recent study provides similar information in a U.K. context. In Phillipson, Bernard, Phillips and Ogg's (1999) investigation of older people's experiences of community change, residents from three towns were interviewed about their neighbourhoods and being a neighbour. Phillipson et al cite the following definition of a typical neighbour:

He, or rather she, was someone who did not expect to spend time in your home or pry into your life, who exchanged a civil word in the street or over the backyard fence, who did not make a great deal of noise, who could supply a drop of vinegar or a pinch of salt if you ran short and who fetched your relatives or the doctor in emergencies. The good neighbour's role was that of an intermediary, in the direct as well as indirect sense … She was the go-between, passing news from one family to another, one household to another. Her role was a communicative, but not intimate, one (Townsend, 1957: 121, cited in Phillipson et al, 1999)

1.9 The authors found that Townsend's definition, though nearly fifty years old, remained relevant. For their participants, talking to someone in the street during the past month, or inviting someone into your house in the past six months, comprised a 'high' level of contact between neighbours. As McGahan (1972) argued, neighbours are friendly, but not too friendly (see also Crow, Allan & Summers, 2002).

1.10 The sociological accounts described above comprise what is still a relatively small literature that focuses specifically on neighbour relationships. Although much is written about community- and neighbourhood-related topics, there remains remarkably little explication of what it means to be a 'neighbour', or how everyday neighbour relationships are managed (although see Laurier et al, 2002). Moreover, a key problem with both the questionnaire and interview-based research described is that, while the latter is designed to deal with the 'reductive' problems of the former, both collect decontextualized information and generalize it from the research context to everyday life. In other words, they treat the information gathered in interviews and questionnaires, about being a 'neighbour' and the activities involved in 'neighbouring', as "surrogates for the observation of actual behaviour" (Heritage & Atkinson, 1984: 2). As Sacks (1992: 27) writes of 'Chicago School' ethnography, "[t]he trouble with their work is that they're using informants; that is, they're asking questions of their subjects. That means that they're studying the categories Members use, to be sure, except at this point they are not investigating their categories by attempting to find them in the activities in which they're employed". So in questionnaire studies, which include 'tick-box' responses to questions and candidate answers proposed by the questionnaire-constructor, we learn little about the situated practices involved in 'being a neighbour' and more about the researcher's preconceptions thereof (Harré, 1979; see Stokoe & Wallwork, 2003). This is relevant to wider debates across the social sciences about the status of interviews as a data-gathering resource (e.g. Edwards & Stokoe, 2004; Potter & Hepburn, 2005; Rapley, 2001), in which researchers ask their participants about their experiences of X, their attitudes towards Y, and then treat the resulting data as a representation of X and Y regardless of the artifactual nature of the data collected.

1.11 In contrast, the aim of this paper is to study naturally-occurring interactions between people who are in the business of being neighbours. It analyses people interacting with each other and various institutional representatives in which what counts as a neighbour relationship, and what it means to be a 'good' or 'bad' neighbour, are the very issues at hand. Therefore, this paper aims to gain some insights into a pervasive but under explored feature of social life: the sights, smells and sounds of people and their neighbours' intimate lives.

Data and Method

2.1 The data set[1] comprises approximately 150 hours of neighbour dispute discourse across different contexts: 30 hours of neighbour mediation; 200 telephone calls to mediation centres; 150 telephone calls to environmental health departments, 130 police-witness interrogations, and approximately 30 hours of neighbour-relevant television and radio broadcasts. All participants consented to have their talk recorded and analysed for research purposes. All names and identifying features of the data have been anonymized.2.2 The recorded data were initially transcribed verbatim. Other sections were further transcribed using Jefferson's (2004) system for conversation analysis. The paper takes an ethnomethodological (Garfinkel, 1967) approach, which involves explicating the 'ethnomethods' that people (members) use to accomplish their everyday lives. It focuses particularly on how complaints about neighbours' activities are produced as transgressions or breaches of the unstated normative social and moral order. Thus the neighbour complaints can be treated as everyday examples of what Garfinkel called the "breaching experiment": disruptions of ordinary action that enable the researcher to "detect some expectancies that lend commonplace scenes their familiar, life-as-usual character, and to relate these to the stable social structures of everyday activities" (ibid.: 37). Although Garfinkel studied artificial breaches (e.g. he instructed his students to act as if they were boarders in their own homes), which contrast somewhat with the norm-oriented practical activities of 'complaining', 'justifying', 'defending' (etc.), we can use neighbour complaints as keys to the concepts and practices that maintain the normative social order (see Cresswell, 1996: 22 on 'spatial Garfinkeling'). This is important since neighbouring functions quietly and goes unexplicated when the order of the relationship is respected and maintained: it is only when breaches occur that people start to articulate the otherwise unspoken norms of social life.

2.3 I therefore collected together all the sequences in which notions of intimacy, privacy, transgression, and knowledge about neighbours, cropped up. Each extract was considered for what it revealed about normative neighbour relationships and their maintenance, what constituted a breach of those relationships, what counted as being a 'good' or 'bad' neighbour, what sorts of accounts these descriptions were embedded within, and what kinds of institutional and interactional activities were being achieved in their construction.

Analysis and Findings

3.1 The first section of the analysis establishes the spatial regulation of normative neighbour relationships. Across the data, the kinds of practices that constitute ordinary (that is, smooth-running, as-yet-unbreached) neighbour relationships were described by participants in two kinds of narrative accounts: in scene-setting descriptions of life before the dispute, and in response to questions from mediators about what clients would like to happen as a result of mediation. What these accounts have in common is the notion that 'good' neighbour relationships are not intimate relations; rather, they occur at the boundaries of private spaces. The second section of analysis examines sequences of talk in which the speakers display different kinds of knowledge about their neighbours' intimate lives, as well as the way expectations about what neighbours are likely to know about each other are collaboratively developed between clients and institutional representatives. Finally, we consider several sequences in which the speakers' complaints (or crimes) turn precisely on the inappropriately public transmission of intimate and personal activities and information.The normative distance of neighbour relationships

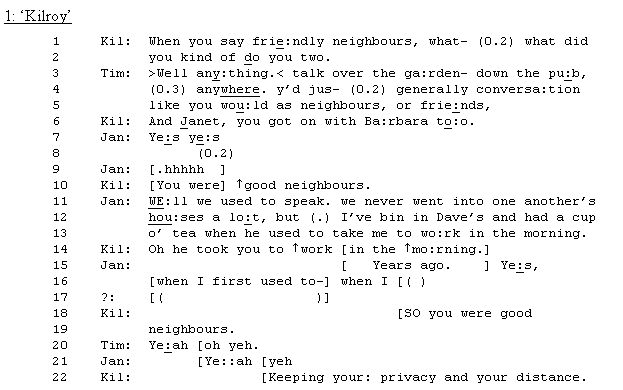

3.2 The first extract comes from a television audience chat-show, hosted by Robert Kilroy-Silk. The programme is devoted to the topic of neighbour disputes, and in this extract Kilroy is eliciting an account of how problems arose.

|

3.3 A key feature of this extract is the collaboratively built definition of what it means to be 'good neighbours' – what it takes to be a member of that category – and the spatial basis of that definition. Good neighbours talk "over the ga:rden (fence)", "down the pu:b", they keep their "privacy" and "distance". As Stokoe and Wallwork (2003) suggest, these practices constitute a relationship that occurs outside, rather than inside, neighbouring homes. Joan claims that "we never went into one another's hou:ses", and although she establishes that she did go "in Dave's" for a "cup o' tea" when her neighbour took her to work, entry into her neighbour's home is a precursor to going out (lines 11-13). Kilroy's response to this information starts with an "Oh", thus treating it as somewhat remarkable and possibly extra to the routine expectancies for 'good neighbours' (see Heritage, 1984). Thus 'good' neighbour relationships are functional and managed contact; neighbours must be friendly but not too friendly.

3.4 Descriptions of what it means to be 'good neighbours' did not crop up randomly across the data, but rather were located in one of two environments: near the start of complaints in a scene-setting narrative, or in response to questions about how the future might look if dispute-free. Extract 1 is an instance of the first environment, in which the audience members describe a trouble-free, pre-dispute period of time in which all parties were 'good neighbours'. This account does some 'identity work' for the speakers, producing them as the kinds of people who know what it means to be good 'neighbours' and are disposed to be reasonable and act appropriately for members of the category.

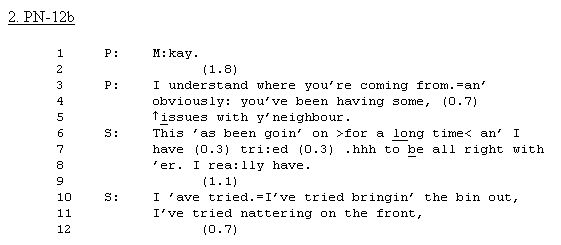

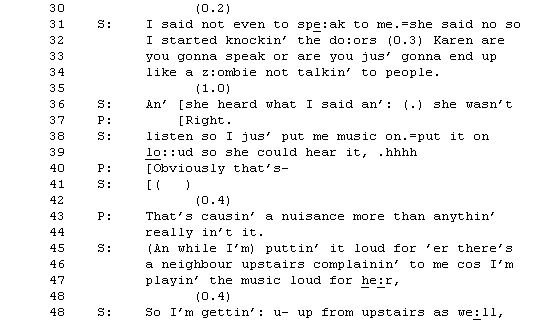

3.5 The next extract comes from a different source, near the start of a police interrogation interview. The suspect (S) has been arrested for a public order offence, in this case for abusive, threatening words and behaviour, and the police officer (P) has invited S to tell her version of events.

|

3.6 In her account of the dispute, S claims that she has "tri:ed" in the past to carry out the activities tied to the category 'good neighbour': "nattering on the front" and "bringin' the bin out,". The combinations of activities ('nattering', dealing with rubbish bins) with locations (on the front, out) in these prepositional phrases display further evidence for the normatively spatial ways of managing neighbour contact at the boundaries of domestic spaces. These activities are described as part of S's turns which also, as in Extract 1, work to produce her as disposed toward good neighbour relations rather than as part of the problem, reciprocally; as not instigating the "↑issues" at hand; and, therefore, as directing blame for the dispute away from S (who has been arrested) towards her neighbour (who has not).

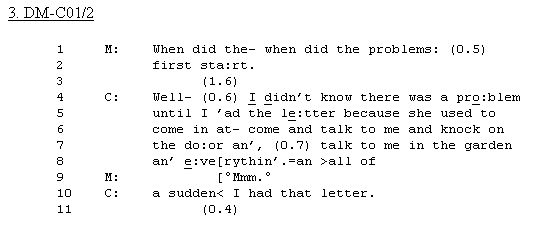

3.7 Extract 3 comes from a mediation session, in which a mediator (M) is interviewing a client (C) who is the subject of a neighbour complaint.

|

3.8 M's question comes at the start of the interview. C's narrative response takes us back to a pre-dispute time when good neighbourly relations were still being maintained, and, as far as she is concerned, this situation prevails: that there are problems is news to her. Note again how neighbour relationships are done accountably through contact at the edges of, or outside, private spaces, something which C orients to in the way she describes 'normal' neighbour relationships: "she used to come in at- come and talk to me and knock on the do:or.". C starts by saying that her neighbour "used to come in at-", but then abandons this, and changes trajectory (doing what conversation analysts call a 'self-initiated, self repair'). What is absent from the restarted description, formulated as a list of activities, is going 'in'. Instead, we hear that she spoke to her neighbour "in the garden" and that the neighbour used to "knock on the do:or" – respecting the door as a marker of privacy and something that is appropriately knocked on, rather than opened without its owner's permission. C completes her 'three-part' list of activities, "an' e:ve[rythin'" (see Jefferson, 1990), thereby characterizing her neighbour relationships as recognizably routine and normal. Finally, C contrasts this routine state of affairs with the arrival of a letter (of complaint), an event that happened "all of a sudden", which is to say inexplicably, with no prior narrative sequentiality (see Stokoe & Hepburn, 2005 on the way speakers mirror lexical content with prosodic features such as the speeded up delivery of "all of a sudden").

3.9 The final extract in this section comes from another individual mediation session, this time with the complaining party. There are two mediators and two clients in this interview, although only M1 and C1 speak here.

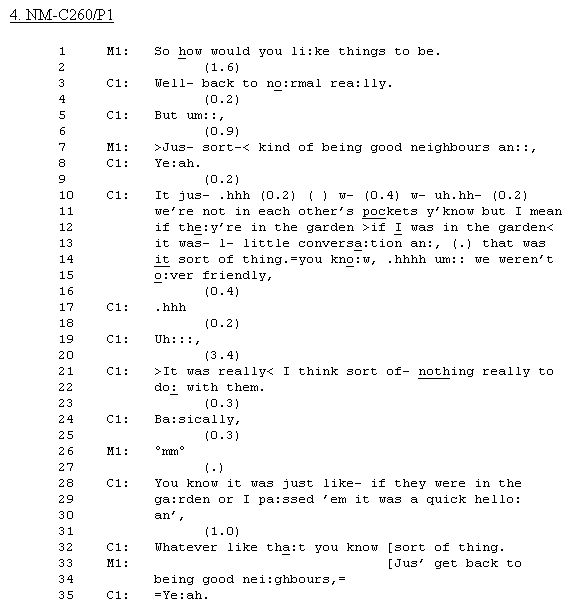

|

3.10 We have observed that descriptions of 'good neighbouring' either occurred early, in accounts of the previous state of the relationship prior to troubles, or in response to mediators' questions about what clients would like to happen in the future. Extract 4 is an example of the second environment, although the clients struggle to formulate these descriptions as answers to questions, rather than when producing them in their own scene-setting narratives. So, after the mediator asks, "how would you li:ke things to be.", a long gap develops before C1 answers "Well- back to no:rmal rea:lly." (lines 1-3). C1 also has some difficulty in characterizing what counts as "no:rmal" (note the pauses and abandoned turn on lines 4-6). M's prompt begs the question ">Jus- sort-< kind of being good neighbours an::,", which is unpacked by C1 in her turns on lines 10-30. A return to being 'good neighbours' includes, as we have come to expect, not being "in each other's pockets", "little conversa:tion[s]" that happen "in the garden", not being "o:ver friendly,", and doing a "quick hello:" if they "pa:ssed" each other ('observation neighbouring': see Bridge et al, 2004). Finally, M formulates the upshot of this description, "jus' get back to being good nei:ghbours,".

3.11 Having demonstrated how people construct neighbour relationships via spatial prepositions, we now move on to investigate the ways neighbours, despite their orientation to privacy, nevertheless routinely and accountably get to know personal things about each other.

Knowledge displays in neighbour complaints

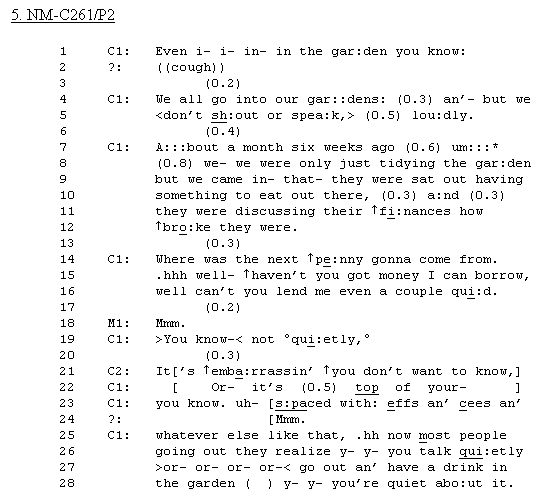

3.12 In each of the following extracts 5-10, the clients or callers (C) are involved in the activity of complaining about their neighbours; either as the instigator of a complaint or as the defender against a complaint, done via the production of counter complaints. Extract 5 comes from the same mediation interview that was introduced at the start of this paper, in which the clients are complaining about their neighbours' noise. In addition to 'noisy sex' reported earlier, the clients are recounting a further complainable incident.

|

3.13 This extract illustrates an interesting blurring of the meaning of garden boundaries, and the locally produced, contingent understandings of 'private' and 'public' spaces. On the one hand, gardens are legitimate sites for neighbours to interact with each other, 'over the fence' (see Extracts 1, 3, 4). On the other, while fences are locations for interaction, they also function to maintain the normative privacy and distance of neighbour relationships. The clients articulate a set of normative rules and appropriate activities for gardens: it is reasonable to drink and talk in them, and tidy them up, but it is complainable to talk loudly and swear in them. Additionally, it is complainable to talk in clear earshot about personal finances and problems. Thus their neighbours should understand about the different symbolic functions of fences, and their permeability, and adapt their behaviour accordingly. If the rules are not observed, then neighbours can get to know such information as each other's financial situation. However, note way C1 and C2 construct their complaint: they were "just tidying" the garden, not deliberately overhearing their neighbours' conversation and so are passive, rather than active, overhearers; this knowledge is unwanted ("↑you don't want to know,"; the use of 'you' produces this as something that anyone would not want to know, not just them), and it causes embarrassment.

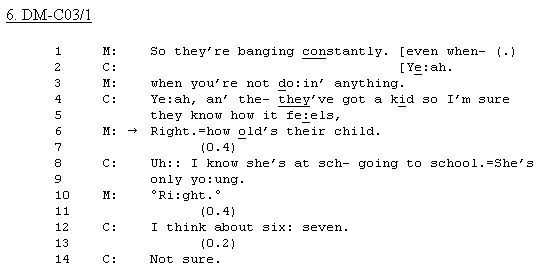

3.14 Extract 6 comes from a mediation interview in which the client has been complained about for making noise. C is doing a counter-complaint: that it is her neighbours, not her, who are making noise.

|

3.15 As she produces her counter-complaint, C displays knowledge of her neighbour's family situation: that they "have a kid". M's follow-up question "=how old's their child.". presupposes that it is expectable for neighbours to have particular kinds of detailed knowledge about each other. M's question does not include an orientation to the possibility that this might not be known of (e.g. "Do you know how old their child is?"). However, C's response (lines 8-9), which turns out to be an account for not knowing the child's precise age, rather than an answer, is epistemologically weaker than M's question. It is produced after a pause, prefaced by "uh::", includes a 'repair' ("I know she's at sch- going to school"), and an orientation to her basis for knowing in the added detail "she's only yo:ung" (lines 8-9). M receipts this information, but adds no more, and after a gap C produces the 'answer': "I think about six: seven.", again downgrading the epistemic certainty of her answer in this and her next turn "Not sure.". We might speculate that although people display some knowledge of each other's private family lives, showing that you know lots of detail risks being hearably 'nosy'.

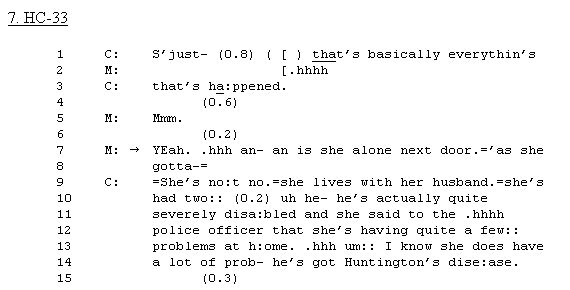

3.16 The next extract comes from a telephone call to a mediation centre. The caller (C) is complaining about her threatening and abusive neighbour. In this sequence, C has just told M that the problems only arise when her own partner is away.

|

3.17 This extract provides a further example of the way the mediator and caller collaboratively occasion and display what neighbours expectably know about each other. M's question, "hhh an- an is she alone next door.='as she gotta-" presupposes that neighbours are entitled to know each other's relationship status, and C answers both parts of his question in her reply: "She's no:t no." and "she lives with her husband". Note that the second part of C's answer supplies the category 'husband', which is one of a handful of potentially relevant categories ('partner', 'boyfriend', 'fella', etc.) that M left open in his question, "'as she gotta-". C continues after answering, displaying more knowledge about her neighbour who has "had two::" (husbands), that the current husband is "quite severely disa:bled", that "she's having quite a few:: problems at h:ome", and that the husband has got "Huntington's disease".

3.18 As we saw in Extract 6, the detail of C's turn between lines 9-14 is important with regards to epistemics and basis for knowing things about your neighbours. C's knowledge that her neighbour is having quite a few:: problems at h:ome" is attributed to the police officer (who has presumably had some involvement in their dispute). However, C asserts her own basis for knowing this – her own epistemic priority – by recycling the reported information ("I know she does have a lot of prob-") and adding further details ("he's got Huntington's disease").

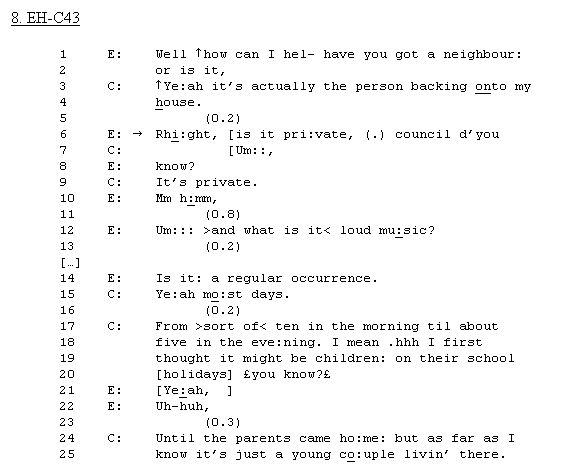

3.19 Extract 8 comes from a call to environmental health services about loud music (several lines about the nature of the noise are omitted from the middle of this sequence).

|

3.20 The call-taker's (E) question, "is it pri:vate, (.) council d'you know?", is formulated differently from the mediators' questions in the previous two extracts: it contains the tag "d'you know", which provides for the possibility that C might not have this knowledge. So while neighbours might be expected to know ages of children, and marital status, they might not know about tenancy status. However, C confirms that her neighbours own their house. This question and answer sequence is relevant to the institutional nature of local authority environmental health, which only deals with private tenants and owner-occupiers. A further interesting feature is the way C, in response to E's question about the regularity of the loud music, reports her 'thought experiments' about the possible reasons for it: "I first thought … but as far as I know" (lines 18-25). So, on the basis of noises heard, people can speculate about their neighbours' family situation. They can move from 'factual' reportings to inference, which may be incorrectly deduced. This is a routine method for complaint-building, as we can see in Extract 9. It comes from a mediation session in which four clients are complaining about a female neighbour and her children.

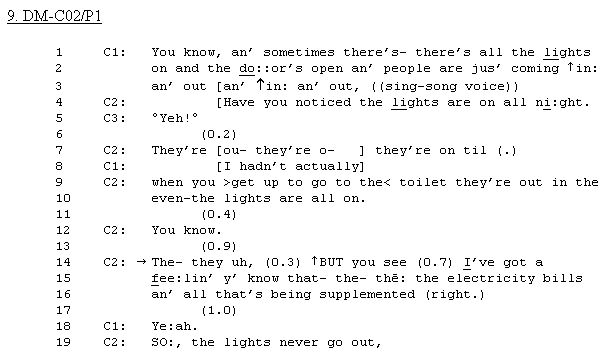

|

3.21 This extract comes from a very lengthy interview, in which the clients have built a detailed account of their neighbour's activities. Here, C1 is producing another 'complainable': the activities of lights being on, the door being open, and people coming "↑in: an' out an' ↑in: an' out,". Her complaint turns on a set of norms for appropriate family and neighbourly living: lights should not be left on, doors are boundaries to private spaces and should be kept closed, and people should be in or out, not move rhythmically from one location to the other.

3.22 C2 builds on C1's observation in the form of a question "have you noticed that the lights are on all ni:ght.". C3 ratifies this observation, although C1 states that she "hadn't actually" noticed. C2's next turn establishes his basis for knowing this 'fact', but at the same time attends to and deletes the possibility that his knowledge results from excessive 'looking' or nosiness: "when you >get up to go to the< toilet they're out in the even-the lights are all on.". So C2, in the course of engaging in the routine activity of going to the toilet in the night (and notice how he formulates this as a generalized, what-anyone-would-do activity), can notice lights blazing without looking deliberately; it is dark outside, so lights are noticeable. Finally, C2 moves from 'factual' observation to speculation ("I've got a fee:lin'") about his neighbour's financial arrangements (that their electricity bills are being "supplemented"), thereby inferring that the neighbours can be reckless with regards to leaving their lights on because they do not pay their own bills – they are those kinds of people.

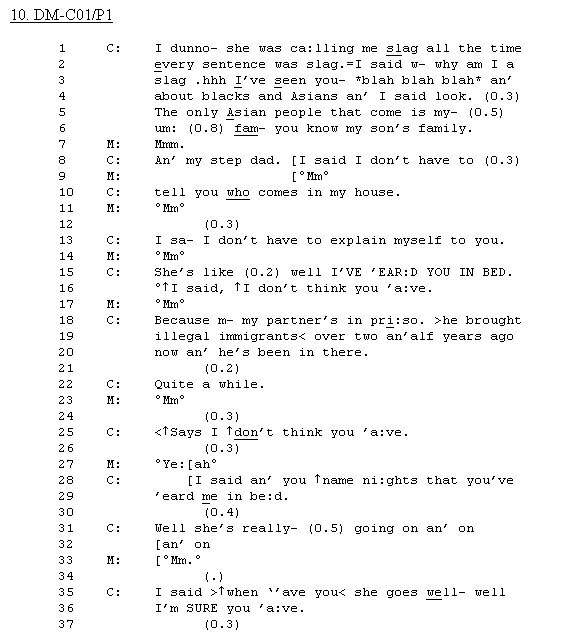

3.23 The final extract in this section provides another instance of the way neighbours may move from observation about some activity to speculation about lifestyle, and how this may be incorrectly deduced. It comes from the mediation session introduced in Extract 3, and here C is countering her neighbour's complaint with one of her own.

|

3.24 C is reporting, in an extended narrative, an encounter between herself and her neighbour in which the neighbour has reportedly called C a "slag". In a series of direct reported claims and counter claims (i.e., C constructs her story using the 'actual' words uttered by herself and her neighbour – a strategy for adding authenticity to accounts), C tells M that the neighbour's basis for her accusation is unfounded: the observations, and therefore her deductions and characterological assessments, are false. For instance, C reports her neighbour's evidential claim, "well I'VE 'EAR:D YOU IN BED.", and her counter "°↑I said, ↑I don't think you 'a:ve. … Because m- my partner's in pri:so.". Thus the neighbour's complaint is based on the inappropriate overhearing of sex noise, and C undermines the veracity of the complaint by asserting alternative 'facts' of the matter.

3.25 This section has explored the kinds of knowledge that neighbours get to know about each other, the entitlements to and basis for such knowledge, and the activities being done of which knowledge displays are a crucial part. The final section of the paper focuses on the inappropriately public transmission of intimate, personal and private activities, details and information between neighbours as a basis for complaint.

Public intimacy in neighbour relationships

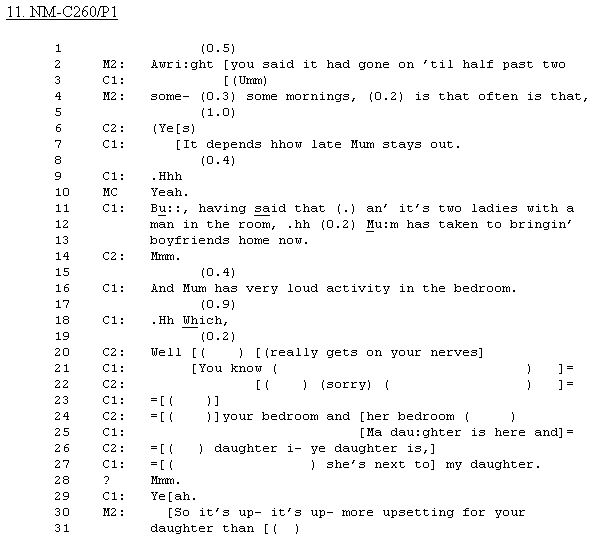

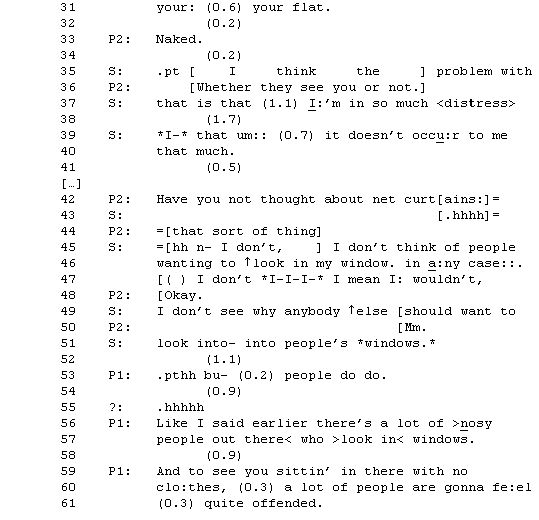

3.26 Extract 11 comes from the same mediation session that was introduced in Extract 4. The clients' complaint is about the noisy children who live next door, with their widowed mother.

|

3.27 Before this extract, the clients have established the main cause for complaint: that the 'mother' is generally out in the evenings, leaving her children undisciplined and making loud noise. In this sequence, C1 produces an account of further complainable noises, this time produced by 'Mum' herself. These noises are associated with her "<very loud activity:> in the bedroom.", occasioned by bringing home "boyfriends", and are understandable as sexual noises. Although C1 does not specify the "activity", it is clear from the locational and other category work that sexual noise and activity is implied ("boyfriends", "bedroom"). C2 adds further descriptive detail, understandable as tied to the category 'sexual activity': "the headboard bangin' the ruddy wa:ll an' 'er mo:anin'.". This is complainable because walls are, normatively, the boundaries between two private spaces. They are barriers, not devices for communication or connection. Note that neither the clients nor the mediators use any direct sexual reference terms, although they do not have any trouble understanding each other. As we have seen, speakers will attend to the potential noxious inferences that can be made about their own identities when engaged in complaining; here, 'good', 'moral' people, who are passive victims of their 'bad' neighbours' activities, do not use particular kinds of language, and do not discuss particular topics, in formal company.

3.28 Finally, consider the reported effects of the noise on the clients, which are separated into two types: the effects on the clients, and the effects on their daughter. For the adults, the effects are further broken down into the consequences if heard occasionally ("you can have a chuckle") compared with regular occurrences ("it really gets on your nerves"). Thus the clients are types of people who are disposed to find these noises amusing and reasonable if the people who produce them do so reasonably and infrequently. Otherwise, their reported reaction is one of irritation and complaint. However, the reported effects on their daughter, whose bedroom wall is the crucial wall in question (lines 24-31), are different: "upsetting". The clients then use their entitlement as incumbents of the category 'parents' to report a further effect of this noise: the effect on their neighbour's own children. C1 states: "I think what upsets us as as pa:rents is her chi:ldren are in there while she's doing thi:s,", and C2 provides the upshot more clearly: "If we can hear 'er her kiddies are right in the next room.". This does more work to attribute the root of the complaint with the irresponsible mother (note that the clients repeatedly formulate her as "Mum", rather than by her name, or 'the neighbour' – it is her status as the mother of children that is the relevant category for their complaint) rather than having any basis in the clients' own reasonable activities (see Stokoe, 2003; Stokoe & Edwards, 2007).

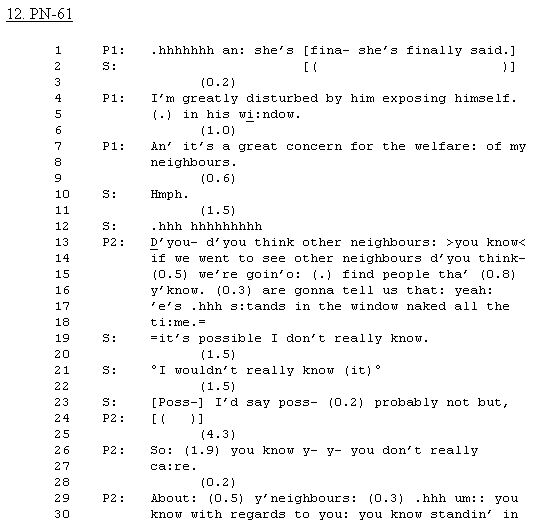

3.29 The next extract comes from the second half of a long police interrogation with a suspect who has been arrested for assaulting his male and female neighbours, one of whom has taken photographs of the suspect while naked in his living room. The issue is whether the suspect is intentionally 'exposing himself' to his neighbours or is entitled to be naked in his own living room. The neighbours have taken photographs as evidence for the first version; the suspect says he has a skin condition that requires the frequent removal of his clothes and application of a medical cream. The police officer has been quoting from the female neighbour's statement, who has said she found the suspect's behaviour to be "aggressive and disgusting. (.) towards assaulting them both."

|

3.30 The main issues at stake are what counts as normal, innocuous and reasonable versus abnormal, provocative and unreasonable behaviour, with regards to being naked in one's own house versus seeing one's neighbour naked in their house. It is also, crucially, about what is permissible and normal viewing/looking behaviour into one's house, by one's neighbours: casual noticing versus sought-out prying. However, these are not straightforward dichotomies. First, the female neighbour's version, as constructed in her statement and voiced by P1, is that S has exposed himself "in his wi:ndow". Although she does not explicitly state that S's actions are deliberate, the attribution of agency is clear: S has 'exposed himself', and not accidentally. In addition to her own disgust, his actions are cause for concern for the "welfare: of my neighbours". S does not produce a lexical response to this report, and P2 recruits the witness's claim about her neighbours' welfare to ask whether, "if we went to see other neighbours d'you think- (0.5) we're goin'o: (.) find people tha' (0.8) y'know. (0.3) are gonna tell us that: yeah: 'e's .hhh s:tands in the window naked all the ti:me.=". P2 therefore puts to S a version of his behaviour that constructs its regularity: something that people might see at any time, not a one-off event.

3.31 P2 formulates the upshot of S's tentative acknowledgement that other neighbours might have seen him naked: that he does not "really ca:re (0.2) about: (0.2) y'neighbours: … whether they see you or not". This is interesting, because while P2's formulation of S's exposure orients to its carelessness (as in our very first example in the Introduction), it does not attribute malicious or criminal intent. S's counter builds on the notion of carelessness, rather than malevolence; but even his carelessness is irreproachable: he is "in so much 3.32 Previously in this interview, the police officers have asked S why, when applying his ointment, he needs to have the curtains open at all. S's account is that he has a smoky fire, and so needs to keep the curtains open to let the smoke out of the window. At line 42, P2 asks whether S has "thought about net curtains:". The issue is whether S has done everything possible to avoid being seen naked by his neighbours, assuming that people do not normatively want to be seen in a state of undress by strangers. S abandons his initial response "hh n-" (which we can reasonably speculate was going to be "no"), and instead challenges the presupposition of the question: that he does not need net curtains because people should not look into his window: " I don't see why anybody↑else should want to look into- into people's *windows.*". This attributes agency to those that look, rather than those that are innocently available to lookers, as well as placing those that look as on the moral lowground: why should they, when he wouldn't (see Edwards, 2006). Thus the basis of these culpable actions in his neighbours' (im)moral dispositions, and not his.

3.33 The final point about this extract focuses on P1's response to S's moral characterizations of himself and his neighbours: "bu- (0.2) people do do. … Like I said earlier there's a lot of >nosy people out there< who >look in< windows. (0.9) And to see you sittin' in there with no clo:thes, (0.3) a lot of people are gonna fe:el (0.3) quite offended.". P1's formulation includes the notion that while people can look intentionally, actively, and nosily, these activities are relatively innocent and reasonable when compared with being naked in one's own house. What counts as 'public', then, is a complicated matter: S is in his house, yet his neighbours' complaint turns on the transmission of inappropriately public intimacy.

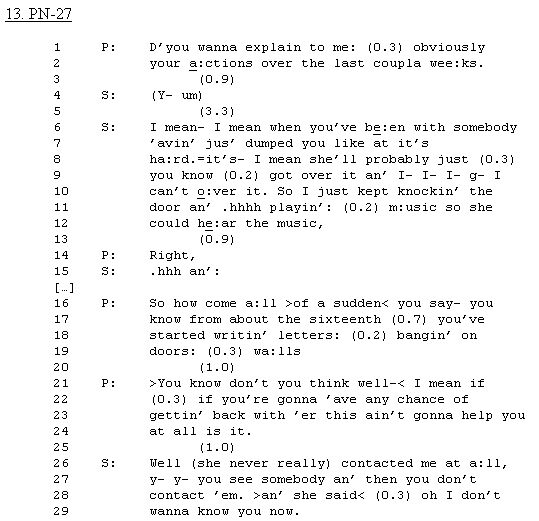

3.34 In the final extract, the suspect has been arrested for breaking a harassment order against his neighbour.

3.35 According to classic social psychological studies, the probability of people becoming friends is partly determined by the structure of their environments. For example, Festinger, Schacter and Back (1950) and Zajonc (1968) found that proximity to other people (that is, living near them) increases the likelihood that they will become friends. So we might speculate that neighbours are in an ideal physical and spatial situation to meet and become friends – or more than friends – with each other. However, as we have seen throughout this paper, while neighbours can be 'friendly' towards each other (see Extract 1), membership of the category 'neighbour' involves maintaining privacy and distance, such that intimate knowledge is a transgression or breach of normative neighbour relations. Extract 13 provides an interesting case in point. S has had a relationship with his female neighbour, the relationship ended, and he has been arrested for breaking a harassment order – which means that he should not contact or approach her. However, because they are neighbours, and thus living in close proximity, S can pass by her door, knock on it, and make noises designed for her to overhear.

3.36 Prior to this extract, the nature of the relationship has been established, as well as the fact that it ended some weeks ago. What is interesting, however, is that because S is still a 'next-door neighbour' of the woman he had sex with; he can exploit their physical proximity to maintain contact. However, as P points out, S's contact via loud music is causing a standard neighbour-noise nuisance with other neighbours. S is in a dilemma: while he plays his music "loud for 'er there's a neighbour upstairs complainin' to me cos I'm playin' the music loud for he:r, (0.4) So I'm gettin': u- up from upstairs as we:ll,".

4.2 Despite the regularly observed orientations to privacy, we also found that neighbours nevertheless get to know, and are expected to know, particular kinds of information about each other. Such information includes marital status, sexual orientation, sexual activity, family set-up, financial situation, how people pay their bills, whether they own their own houses, how old their children are, and so on. We observed that such knowledge was treated as an entitlement of the category 'neighbour’; collaboratively occasioned between neighbours and institutional representatives (mediators, police officers, environmental health officers), but also carefully managed in the epistemic orientations of neighbours and their deployment of particular strategies to avoid being seen as nosy, motivated, unreasonable, or disposed to cause problems. We noted that, in the construction of their complaints and counter complaints, people move from 'factual' observation about their neighbours' activities to speculation about their lifestyle, and that this may be incorrectly deduced and denied.

4.3 In summary, this paper has contributed to the small but growing literature on the topic of neighbour relationships. The transmission and observation of intimate information between neighbours, whether done naively, recklessly or intentionally, is perhaps unavoidable for those living in close proximity. This paper has shown how neighbour relationships are managed and defined, where they are located, and how they are breached, all defined in and for the actual practices of neighbour interaction, and engagement with agencies of complaint, mediation and control.

BRIDGE, G., Forrest, R., & Holland, E. (2004). Neighbouring: A review of the evidence. University of Bristol: ESRC/Centre for Neighbourhood Research.

BRONZAFT, A.L. (2002). Noise pollution: A hazard to physical and mental well-being. In R. Bechtel & A. Churchman (Eds.), Handbook of Environmental Psychology. New York: Wiley and Sons.

BROWNING, G. (2004). Never hit a jellyfish with a spade: How to survive life's smaller challenges. London: Atlantic Books.

CHUANG, Y.C., Cubbin, C., Ahn, D., & Winkleby, M.A. (2005). Effects of neighbourhood socioeconomic status and convenience store concentration on individual level smoking. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59 (7), 568-573.

CRESSWELL, T. (1996). In place/out of place: Geography, ideology and transgression. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

CROW, G. & Allan, G. (1994). Community life: An introduction to local social relations. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

CROW, G., Allan, G., & Summers, M. (2002). Neither busybodies nor nobodies: Managing proximity and distance in neighbourly relations. Sociology, 36 (1), 127-145.

DIXON, J.A.,, & Durrheim, K. (2000). Displacing place identity: A discursive approach to locating self and other. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 27-44.

VAN DONGEN, J.E.F. (2001). Noise annoyance from neighbours. Inter-Noise: The 2001 International Congress and Exhibition on Noise Control Engineering. The Hague, August.

EDWARDS, D. (2006, In press). Facts, Norms and Dispositions: Practical uses of the modal would in police interrogations. Discourse Studies, 8 (4), 475-501.

EDWARDS, D., & Stokoe, E.H. (2004). Discursive psychology, focus group interviews, and participants' categories. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 22, 499-507.

FESTINGER, L., Schachter, S., & Back, K.W. (1950). Social pressures in informal groups: A study of human factors in housing. New York: Harper.

GALSTER, G. (2001). On the nature of neighbourhood. Urban Studies, 38 (12), 2111-2124.

GANS, H.J. (1962). The urban villagers: Group and class in the life of Italian-Americans. New York: Free Press.

GARFINKEL, H. (1967). Studies in Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

GRIMWOOD, C., & Ling, M. (2001). Domestic noise: Furthering our understanding of the issues involved in neighbourhood noise disputes. Clear Air, 31, 101-106.

GUNN, S. (2001). The spatial turn: Changing histories of space and place. In S. Gunn & R.J. Morris (Eds.), Identities in space: Contested terrains in the Western city since 1850. Aldershot: Ashgate.

GURNEY, C.M. (2000). Transgressing private-public boundaries in the home: a sociological analysis of the coital noise taboo. Venereology, 13 (1), 39-46

HARRÉ, R. (1979). Social being: A theory for social psychology. Oxford: Blackwell.

HERITAGE, J.C. (1984). A change-of-state token and aspects of its sequential placement. In J.M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

HERITAGE, J.C., & Atkinson, J.M. (1984). Introduction. In J.M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

JEFFERSON, G. (1990). List construction as a task and resource. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Interaction competence. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

JEFFERSON, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. Lerner (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

MCGAHAN, P. (1972). The neighbour role and neighbouring in a highly urban neighbourhood. Sociological Quarterly, 13, 397-408.

LAURIER, E., Whyte, A., & Buckner, K. (2002). Neighbouring as an occasioned activity: "Finding a lost cat". Space & Culture, 5 (4), 346-367.

LEE, B.A., & Campbell, K.E. (1997). Common ground? Urban neighbourhoods as survey respondents see them. Social Science Quarterly, 78 (4), 922-936.

PARK, R., Burgess, E., & McKenzie, R.D. (1925). The city. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

PHILLIPSON, C., Bernard, M., Phillips, J., & Ogg, J. (1999). Older people's experiences of community life: Patterns of neighbouring in three urban areas. Sociological Review, 47 (4), 715-743.

POTTER, J., & Hepburn, A. (2005). Qualitative interviews in psychology: Problems and prospects. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2 (4), 281-308.

PREZZA, M., Amici, M., Roberti, T., & Tedeschi, G. (2001). Sense of community referred to the whole town: Its relations with neighbouring, loneliness, life satisfaction and area of residence. Journal of Community Psychology, 29 (1), 29-52.

RABAN, J. (1974). Soft city. London: Hamish Hamilton.

RAPLEY, T. (2001). The art(fulness) of open-ended interviewing: Some considerations on analysing interviews. Qualitative Research, 1 (3), 303-333.

SACKS, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation (Vols. I & II, edited by G. Jefferson). Oxford: Blackwell.

SKJAEVELAND, O., & Garling, T. (1997). Effects of interactional space on neighbouring. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 17, 181-198.

STOKOE, E.H. (2003). Mothers, single women and sluts: Gender, morality and membership categorization in neighbour disputes. Feminism & Psychology, 13 (3), 317-344.

STOKOE, E.H., & Edwards, D. (2007, In press). Mundane morality and gender in familial neighbour disputes. In J. Cromdal & M. Tholander (Eds.), Children, morality and interaction. London: Equinox.

STOKOE, E., & Hepburn, A. (2005). "You can hear a lot through the walls": Noise formulations in neighbour complaints. Discourse & Society, 16 (5), 647-673.

STOKOE, E.H., & Wallwork, J. (2003). Space invaders: The moral-spatial order in neighbour dispute discourse. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 551-569.

UNGER, D.G, & Wandersman, A. (1983). Neighbouring and its role in block organisations: An exploratory report. American Journal of Community Psychology, 11 (3), 291-300.

VALLANCE, S., Perkins, H.C., & Moore, K. (2005). The results of making a city more compact: Neighbours' interpretations of urban infill. Environment and Planning B, 32 (5), 715-733.

WARR, D.J. (2005). Social networks in a 'discredited' neighbourhood. Journal of Sociology, 41 (3), 285-308.

WILLMOTT, P. (1963). The evolution of a community. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

ZAJONC, R.B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, Monograph supplement No. 2, Part 2.

Discussion and Conclusions

4.1 This paper has examined the neighbour relationship context as an interesting, yet understudied, example of non-familial intimacy. A key theme of the analysis focused on the way neighbours are oriented to distance and privacy in their relationships whilst also, by virtue of their close physical proximity and shared boundaries, transmit and observe personal information about each other as they go about their everyday lives. Neighbours engage in a number of practices in order to maintain good neighbourly relationships, including engaging with each other at the edges of private spaces: 'on the front', 'over the fence', 'in the garden', or 'at the door' (see Stokoe & Wallwork, 2003). These spaces function as the boundaries of private spaces, and are the sites of normative neighbour relationships that occur outside, rather than inside, domestic spaces. Complaints and disputes, therefore, often have their basis in the illegitimate transgression or breach of more or less permeable boundaries: the excessive, rather than reasonable and normative, sounds and sights that come 'through the wall', 'over the fence', or 'out of the window'. However, 'public' and 'private' space cannot be defined objectively. What counts as private and public is open to negotiation; to be constructed one way or the other depending on the context and interactional goals of the speaker. For example, gardens are spaces for interacting with the neighbours, but they are bound by fences and walls to be private. Depending on the activities one engages in (e.g. sitting naked, looking into someone's house through their window), domestic interiors can be constructed as public spaces, about which neighbours can take offence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Derek Edwards, Jonathan Potter and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Notes

1 The majority of this corpus has been collected as part of ESRC grant number RES-148-25-0010 "Identities in neighbour discourse: Community, conflict and exclusion" held by Elizabeth Stokoe and Derek Edwards.

References

BONAIUTO, M., Bonnes, M., & Constinsio, M. (2004). Neighbourhood evaluation within a multiplace perspective on urban activities. Environment and Behaviour, 36 (1), 41-69.